On Friday, two hours after officials in Pennsylvania announced the batch of votes that secured the White House for a native son of Scranton, a smattering of red hats padded across the front lawn and clambered up the steps of the Louisiana state Capitol in Baton Rouge.

The MAGA loyalists—estimated to number around 200, almost none of whom wore face masks— were there to protest an election they believe had been stolen from incumbent President Donald Trump, alleging a rambling mess of baseless, bizarre, and often contradictory claims.

A middle-aged white man in overalls got choked up when talking about how much Trump had given up in order to pursue a career in politics. He urged the crowd to recall elected officials who accepted the results of the election. Timothy J. Gordon, a conservative talk radio host and far-right provocateur who, in June, was fired from his teaching job at a Catholic high school after publicly asserting that the Black Lives Matter movement was a “terrorist organization” that had “prearranged piles of weapons, rocks” to incite violence at protests, drove in from California.

Gordon, who appeared alongside handmade “Catholics for Trump” signs, warned of an impending “color revolution” against Trump, parroting a theory most commonly associated with authoritarian regimes like Vladimir Putin’s Russia and Xi Jinping’s China. “The term color revolution was coined in the early aughts to describe four political revolutions in post-Communist Europe and Central Asia, in which repressive regimes tried to hold on to power after losing an election,” Thomas Wright, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, explained in The Atlantic in September.

In short, Gordon believes that the opposition to Trump is a creation of a cabal of “deep state” actors and NGO funders like George Soros.

“The original color revolutions occurred when the perception of clear and massive electoral fraud was widespread and protesters were angry about having democratic rights taken away. The demonstrations were directed at illegitimate regimes with a history of rigged elections, endemic corruption, and repression of political opponents,” Wright noted.

“STOP THE COUNT!” Trump tweeted Thursday morning.

While Gordon may have not been well-known among the crowd gathered outside of the House that Huey Built, there was at least one familiar face in the audience.

A former state representative from Houma named Lenar Whitney, a mousy blonde woman who is perhaps best known for once bizarrely asserting that she could disprove climate change with a thermometer, was also there.

“Never have I met any candidate quite as frightening or fact-averse as Louisiana state Rep. Lenar Whitney,” Dave Wasserman once wrote in The Washington Post.

This year, Whitney served as the Louisiana GOP’s National Committeewoman; she appeared in the Republican National Convention’s video montage of the ceremonial roll call, standing alone in front of Jackson Square in New Orleans and pledging Louisiana’s delegates to Donald Trump.

At the event in Baton Rouge (and on her Facebook page), she promoted a comically stupid theory involving President Trump surreptitiously planting a watermark on ballots that would expose voter fraud.

“She said the gathering was an outlet for Trump supporters to express that they ‘are standing with our president,'” reported Sam Karlin of The Advocate.

Whitney learned of the event through Facebook, she said.

After amassing more than 350,000 followers, Facebook banned the group “Stop the Steal” once members began posting calls to incite violence at planned protests across the country.

The protests were the brainchild of Ali Alexander, a controversial far-right operative who boasts more than 140,000 followers on Twitter, where he’s simply @ali.

“Alexander appears to be involved with Stop The Steal both through his tweets promoting it and through his links to one of the websites boosting it,” Mother Jones reported Friday. “Stopthesteal.us’s domain is registered to Vice and Victory, a possibly defunct political consultancy he’s affiliated with. After clicking the site’s donate button, visitors are prompted with the option to donate money to one of several cryptocurrency addresses associated with Alexander, or given links to his Paypal, CashApp, and Amazon wishlist.”

Here in Louisiana, Alexander is better known by his legal name, Ali Akbar. Although he now lives in Texas, for the past four years, Alexander resided in Baton Rouge, a fact that has gone virtually unnoticed in the torrent of coverage he’s recently generated.

In June 2019, Alexander made national headlines for a racist tweet that asserted Kamala Harris was not “an American Black” because her father was Jamaican. His comment was retweeted and then later deleted by the president’s son, Donald Trump, Jr. The next month, Alexander was one of several controversial figures invited to the White House’s “social media summit.”

There’s more.

“According to a 2018 Politico report, the night before the 2016 election, a PAC advised by Alexander received a $60,000 donation from hedge-fund billionaire Robert Mercer, the pro-Trump billionaire,” Right Wing Watch’s Jared Holt reported in September. “Alexander has associated with far-right figures including Unite the Right white supremacist attendee Matt Colligan, and made a habit of noting when members of the media he criticizes are Jewish, according to The Observer.”

In an August profile of Alexander, the Daily Dot reported that he had “found a niche among the likes of anti-Muslim activist and Republican Florida congressional candidate Laura Loomer and blundering political fraudster Jacob Wohl….The trio went to Minneapolis in June 2019 to film a documentary called Importing Ilhan, which was severely mocked online for lacking credibility. The video they produced was aimed at proving Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) had married her brother. While filming, they also wore bulletproof jackets only to turn out to report fake death threats against themselves to authorities.”

Weeks before the election, Alexander promoted a website that floated the bogus claim that Joe Biden secretly suffered from Parkinson’s disease.

Earlier today, he confirmed his role in the Stop the Steal protests to me via text message. He was not present at the event in Baton Rouge; instead, he attended a protest in Austin, alongside Infowars founder Alex Jones.

Although he tells me that the event in Baton Rouge came together in only 23 hours, he previously announced plans for the event—and similar events across the nation—nearly two months ago. (He says he abandoned these plans some time in October).

“In the next coming days, we’re going to build the infrastructure to stop the steal,” Alexander said in a Periscope video posted in early September. “What we are going to do is we’re going to bypass all of social media. In the coming days, we will launch an effort concentrating on the swing states, and we will map out where the votes are being counted and the secretary of states. We will map all of this out for everyone publicly and we will collect cell phone numbers so that way if you are within 100 mile radius of a bad secretary of state or someone who’s counting votes after the deadline or if there’s a federal court hearing, we will alert you of where to go. We’re going to bypass all of Twitter, all of Facebook, all of Instagram, OK? We’re going to bypass it all.”

A few days prior, Alexander claimed to be at least partly responsible for organizing an armed mob outside of the Maricopa County Election Center, and when it started to become clear that Joe Biden would pull off an upset in Georgia, the Trump campaign filed a lawsuit seeking to halt the count, based solely on an affidavit provided to them by Sean Pumphrey of South Carolina, who the Bayou Brief has discovered to be connected to Alexander via Facebook. The lawsuit was quickly dismissed.

A similar lawsuit was recently filed in Pennsylvania, after a postal service “whistleblower” alleged he overheard colleagues discuss back-stamping mail-in ballots. The whistleblower first brought his claims to the attention of James O’Keefe, who has been friends with Alexander for more than seven years.

I’ve known Ali since 2015, when he served as the Digital Director of Republican Jay Dardenne’s gubernatorial campaign. We’ve appeared opposite of one another at least twice on Jim Engster’s statewide talk radio show, where the conversations were always civil and substantive, which is one of the reasons I’ve been so surprised to discover how dramatically different the “Ali Alexander” of social media stardom is from the Ali Akbar I knew through Louisiana politics. (After learning that he was the owner of the Twitter handle @louisiana, I also unsuccessfully lobbied him at least twice to let me take over the dormant account).

Engster’s impression of the young activist was similar to mine. “Ali was a passionate and true believer of conservative politics, not an opportunist like many of his cohorts,” Engster recalled.

To those who know him exclusively through his work in Louisiana, Ali’s evolution into full-blown MAGA diehard—and his transformation into an outspoken and notorious firebrand—seems remarkable for a few reasons, not the least of which being that he was initially a reluctant supporter of Trump. In hindsight, however, it now seems obvious that his ambivalence was largely performative.

“I think he destroyed my party, and I hate the campaign he’s running,” Ali wrote on Facebook about Trump a few days before the final round of primary contests in 2016. He added, “But I’ll gladly choose him over Hillary Clinton and the violent leftist mob.”

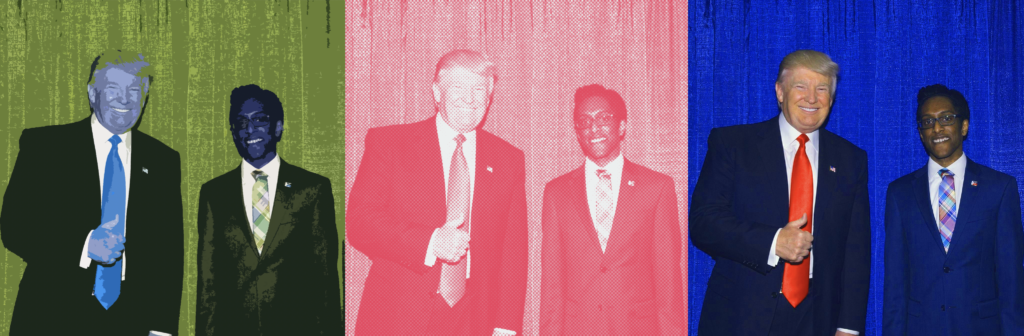

The two had actually met well before Trump descended down the golden escalators. According to Ali, he had been “the only person sitting in the room” when an unnamed Republican candidate sought Trump’s support at the 2014 Republican Leadership Conference in New Orleans. The future president was impressed by how much Ali resembled Sammy Davis, Jr., he said, and they ended up talking with one another for close to 45 minutes. Apparently, he’d left an impression. Years later, when Ali visited the White House, Trump remembered the Sammy Davis lookalike.

At the 2014 RLC, Ali also snapped a photo of the Donald being interviewed for a podcast hosted by the new head of Andrew Breitbart’s media empire.

Notably, Ali’s involvement in Louisiana predates the 2015 gubernatorial campaign. A few months after the RLC in New Orleans, a mysterious new political action committee, Black Conservatives Fund, announced they would be opening their first-ever state chapter in Louisiana. “It’s unclear who will be leading the group’s efforts in Louisiana or the scale of those efforts,” The Advocate reported at the time.

The Black Conservatives Fund, as it turns out, was Ali Akbar. (He has recently used the PAC’s Twitter account to amplify his other endeavors). Although it’s been dormant since 2016, according to the organization’s last FEC report, it’s still sitting on more than $200,000 in cash.

The Black Conservatives Fund appears to have largely been a proxy for former Louisiana state Sen. Elbert Guillory, a Black Republican from Opelousas. The PAC emerged during the 2014 Senate race between three-term incumbent Democrat Mary Landrieu and Republican congressman Bill Cassidy. At the time, Guillory was putting together what would be an ultimately unsuccessful campaign for lieutenant governor.

The PAC first made waves after releasing secretly recorded audio of Landrieu’s then-Chief of Staff, Don Cravins, Jr. (whose father, one of Guillory’s political nemeses, was then serving as Mayor of Opelousas) promising a gathering of Democrats that Landrieu would continue supporting President Obama “97% of the time” if reelected.

Cassidy’s entire campaign had been built on the message that Landrieu was merely a rubber-stamp for the Democratic president, who was deeply unpopular in Louisiana. The statistic, however, was grossly misleading. Landrieu was known for her independent streak, and using the same metric, Cassidy, as a member of the House, had also voted in support of bills that were later signed into law by President Obama 97% of the time.

To many, Cassidy’s message was nothing more than a dog whistle, and Cravins’ comments, which were delivered in front of a majority Black audience, were not a confession of anything duplicitous; rather, they were a statement of support for the nation’s first Black president. The Black Conservatives Fund’s other major play in the 2014 campaign was an expensive robocall targeting Black voters that selectively edited comments Landrieu made to conservative talk radio host Jeff Crouere about the Affordable Care Act in order to imply that she had voted against President Obama.

At the time, Alexander had still been living in Fort Worth, and when the Dardenne campaign hired him as a Digital Director, he hadn’t yet built an online persona. Even his role in the Black Conservatives Fund had been obscured; he called himself a “senior advisor” and, for the most part, preferred to stay behind-the-scenes. Privately, those involved in Dardenne’s campaign have expressed regret over hiring Alexander and claim to be appalled by the dirty tricks that have become a hallmark of his brand.

When I asked him about his Stop the Steal campaign, Ali provided what, to me, seemed like a perfectly reasonable argument in favor of free, fair, and transparent elections; he also distanced himself from the theories espoused by Whitney. “(The) only uniting message for StopTheSteal is that the election should be predictable and the counting should be transparent,” he wrote. “It’s not. And we feel like things are being hidden so open it up or we’ll assume the worst.” But the measured words and tone he expressed to me privately are belied by his online antics, and it’s impossible not to be alarmed and deeply concerned by the very real chance that Ali endangers himself and others with his reckless hyperbole. (He’s taken to wearing a bulletproof vest when he appears in public).

But more than anything else, Ali’s decision to begin planning the infrastructure for Stop the Steal long before the first ballot had ever been cast suggests that these protests were going to happen regardless of how the election actually shaped up.

Like Sammy Davis, Jr., Ali Alexander is one helluva performer, and the show must go on.