“It’s something everybody looks for,” state Rep. Alan Seabaugh (R- Bossier City) explained in 2015. “It factors into fundraising when it comes to re-election time.”

Seabaugh wasn’t referring to the number of bills he sponsored or authored. He wasn’t talking about the laws he helped pass or even the amount of money he was able to bring back to his district. He was, instead, openly acknowledging the pecuniary necessity of earning a top score from the most powerful lobbying organization in the state, the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry (LABI). In 1999, LABI launched a new initiative, a so-called “legislative scorecard.” The organization would give each and every legislator a grade; if a legislator voted in line with LABI’s recommendations 70% or more of the time (today it’s 80%), they would receive an automatic endorsement from the organization and, in subsequent years, a concomitant campaign contribution from at least one of LABI’s four political action committees. (LABI claims that contributions are given based on a four-year cumulative score, but a comprehensive analysis of campaign finance reports proves otherwise).

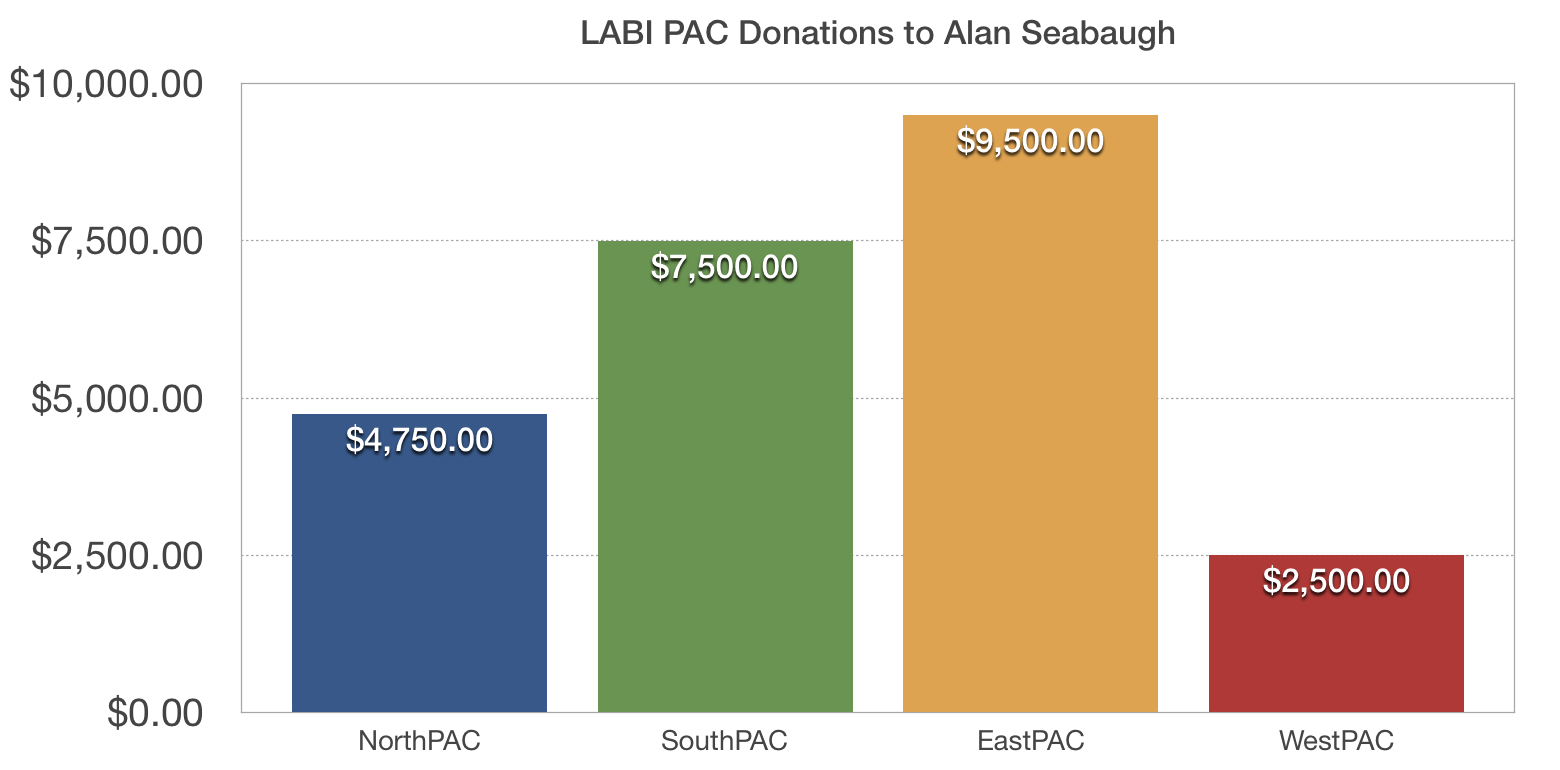

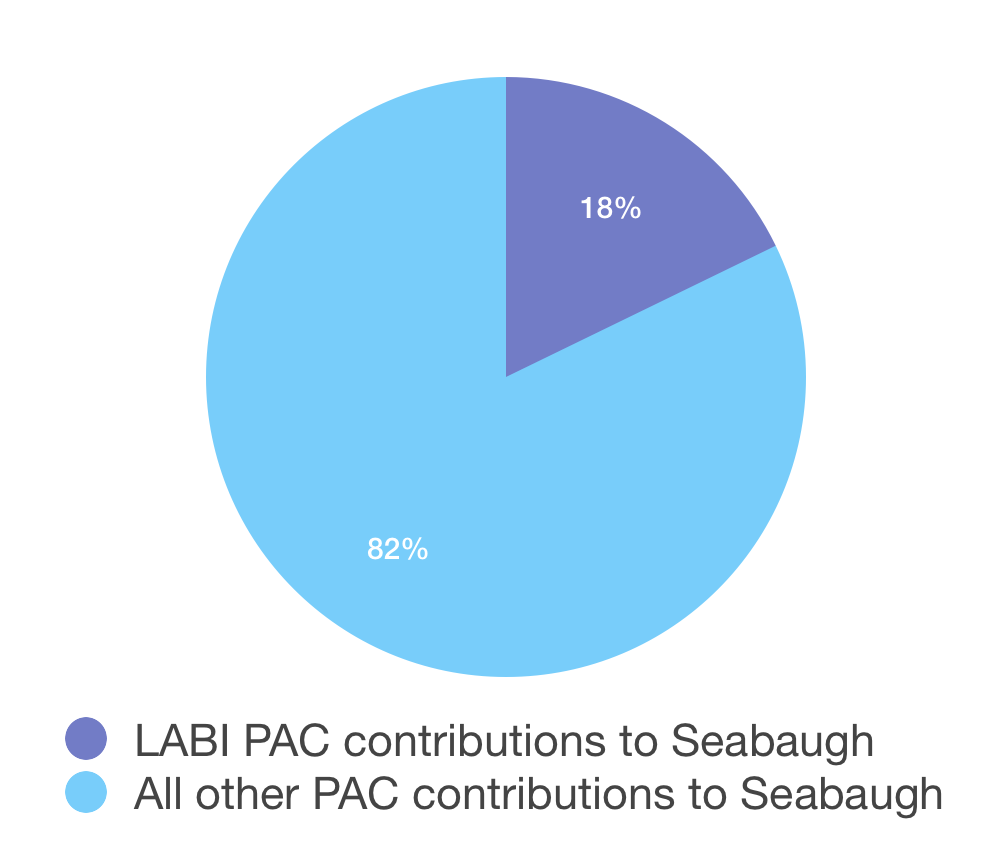

In return, LABI has showered Seabaugh’s campaign with nearly $25,000 in donations from all four of its political action committees. During his eight years in office, Seabaugh has received over $136,000 in donations from PACs; if he had accepted any more PAC donations, he would have come awfully close to exceeding the legal limit.

In return, LABI has showered Seabaugh’s campaign with nearly $25,000 in donations from all four of its political action committees. During his eight years in office, Seabaugh has received over $136,000 in donations from PACs; if he had accepted any more PAC donations, he would have come awfully close to exceeding the legal limit.

Perhaps the most astonishing thing about Alan Seabaugh’s admission is that it’s taken three years for someone to point out that it was, in fact, an astonishing admission. It may not be against the law or prima facie evidence of political corruption, but at the very least, voters should be rightfully alarmed whenever a lawmaker casually reveals that his voting record is directly informed by the financial benefits of following a special interest group’s scorecard.

Of course, there is nothing exactly unusual or even wrong when an organization contributes to an elected official who supports their agenda, but the way LABI has structured their political lobbying and electioneering strategy- the whole concept of automatic endorsements and campaign contributions, well, that is extraordinarily unusual.

Alan Seabaugh is currently being considered by President Donald Trump for a federal judgeship.

If he’s nominated, he will face questioning on federal laws. He should consider polishing up good answers to a series of questions about quid pro quo contributions, the Hobbs Act, the tension between the Court’s holdings in McCormick and Evans, and the federal funds bribery statue, which is appropriately numbered §666. The federal courts have defined quid pro quo very simply as “something for something.”

****

Perhaps the most astonishing thing about Alan Seabaugh’s admission is that it’s taken three years for someone to point out that it was, in fact, an astonishing admission. It may not be against the law or prima facie evidence of political corruption, but at the very least, voters should be rightfully alarmed whenever a lawmaker casually reveals that his voting record is directly informed by the financial benefits of following a special interest group’s scorecard.

Of course, there is nothing exactly unusual or even wrong when an organization contributes to an elected official who supports their agenda, but the way LABI has structured their political lobbying and electioneering strategy- the whole concept of automatic endorsements and campaign contributions, well, that is extraordinarily unusual.

Alan Seabaugh is currently being considered by President Donald Trump for a federal judgeship.

If he’s nominated, he will face questioning on federal laws. He should consider polishing up good answers to a series of questions about quid pro quo contributions, the Hobbs Act, the tension between the Court’s holdings in McCormick and Evans, and the federal funds bribery statue, which is appropriately numbered §666. The federal courts have defined quid pro quo very simply as “something for something.”

****

“When people weren’t paying any taxes and the oil and gas money rolled in, you could run things like a banana republic,” LSU political science professor Wayne Parent explained to The Christian Science Monitor in late October 2002, only a few days after former Gov. Edwin Edwards reported to prison. “Cajun-country era ends, prison term begins,” the headline blared.

“When people weren’t paying any taxes and the oil and gas money rolled in, you could run things like a banana republic,” LSU political science professor Wayne Parent explained to The Christian Science Monitor in late October 2002, only a few days after former Gov. Edwin Edwards reported to prison. “Cajun-country era ends, prison term begins,” the headline blared.

… the chief principle of banana-ism is that of kleptocracy, whereby those in positions of influence use their time in office to maximize their own gains, always ensuring that any shortfall is made up by those unfortunates whose daily life involves earning money rather than making it. At all costs, therefore, the one principle that must not operate is the principle of accountability….. In a banana republic, the members of the national legislature will be (a) largely for sale and (b) consulted only for ceremonial and rubber-stamp purposes some time after all the truly important decisions have already been made elsewhere….Believe it or not, Wikipedia has one of the best distillations of Hitchens’ larger economic argument (emphasis added):I was very struck, as the liquefaction of a fantasy-based system proceeded, to read an observation by Professor Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld, of the Yale School of Management. Referring to those who had demanded—successfully—to be indemnified by the customers and clients whose trust they had betrayed, the professor phrased it like this:

These are people who want to be rewarded as if they were entrepreneurs. But they aren’t. They didn’t have anything at risk.

That’s almost exactly right, except that they did have something at risk. What they put at risk, though, was other people’s money and other people’s property. How very agreeable it must be to sit at a table in a casino where nobody seems to lose, and to play with a big stack of chips furnished to you by other people, and to have the further assurance that, if anything should ever chance to go wrong, you yourself are guaranteed by the tax dollars of those whose money you are throwing about in the first place!

In economics, a banana republic is a country with an economy of state capitalism, by which the country is operated as a private commercial enterprise for the exclusive profit of the ruling class. Such exploitation is effected by collusion between the State and favored economic monopolies, in which the profit derived from the private exploitation of public lands is private property, while the debts incurred thereby are the financial responsibility of the public treasury.When Wayne Parent optimistically spoke about the end of Louisiana’s “banana republic” century, he wasn’t really making a declaration; he was saying a prayer for his beloved home state. In the years since, countless articles have been written about how America itself has transformed into a banana republic (none as good as Christopher Hitchens’ essay, though), and perhaps as a consequence, the term has lost much of its meaning and significance. But a banana republic isn’t a dictatorship; it’s not dependent on a charismatic and corruptible leader. Put another way, Huey P. Long didn’t turn Louisiana into a banana republic; Standard Oil did. “Would you go along with this statement?” Gus Weill asked James Carville in 1991. “That there’s something either in our air or our drinking water that attracts kids, boys and girls, to politics?” “Yeah, this is a theory,” Carville said, “and I’ll put it out there. There’s a great oral tradition here. There’s a great lust and love for entertainment. And it’s been said, point and jest, but I guess there’s some grain of truth here- that we expect our politicians to entertain us more than lead us. Unfortunately, we’ve been entertained more than we’ve been led.” The featured image in this article is a satirical press release. Everything else is depressingly true. Read Part One of this series here.