The problem was, the well – serial number 250498, and known familiarly as “Indigo White 1”, ended up somewhere it wasn’t supposed to be. The tail end of the well was nearly a hundred feet closer to the wellhead of a pre-existing fracked well than it was supposed to be.

“The issue today is that Indigo White is 247 feet from Churchman H36, instead of the 330 feet that was as permitted,” DNR’s Todd Keating, who was presiding over the hearing, said disapprovingly.

“200 feet from the center internal is the standard,” Shealey said, defending the error. “If we hadn’t done this, the available hydrocarbons would have otherwise been abandoned. Besides, this is all 16-thousand feet deep.”

Dave Comeaux, a geologist retained by Indigo as an expert witness, acknowledged the Indigo White well is successfully producing about 16000 mcfs of natural gas per day since the initial frack in April.

“As of the end of June, the well had produced more than a billion cubic feet of gas,” Comeaux testified.

Besides, Shealy argued, the Churchman well (also operated by Indigo) had been “shut in” – stopping the pumping of pressurized fracking fluid into the well – in January, while drilling and placement of reinforced pipe was completed on the White well.

Comeaux explained that the drilling company then pulled the pipe and liner from the Churchman well, and set new pipe and liner in it. Indigo fracked the White well, then refracked the Churchman well just days apart.

The hearing officers seemed concerned by the intensity of activity concentrated in one place, and questioned the wisdom of fracking two wells so close together in both time and distance.

Shealy insisted it was both necessary and usual practice.

“It is wise to treat this as one big project, and it’s common to refrack when a nearby well is coming on line – to minimize the pressure differentials,” the lawyer said, adding, “Of course, I can’t elaborate here – it’s a protection matter, you know?”

The hearing officers then asked the geologist if “stimulating converging laterals” was standard practice.

“It might be common,” Comeaux said hesitantly and more than a bit reluctantly. “I don’t know. I do know in this case, it was done without incident.”

Shealy insisted this is the most economical way for the company to operate.

“Indigo considers it necessary to drill the field as essentially one big project,” Shealy said. “We have three wells going out from the White drilling pad, and two wells from the Churchman pad. The cost savings on these five wells is $1.5-million. That’s why Indigo prefers to drill multiple cross unit laterals, keeping our rigs in the field and moving them from pad to pad.”

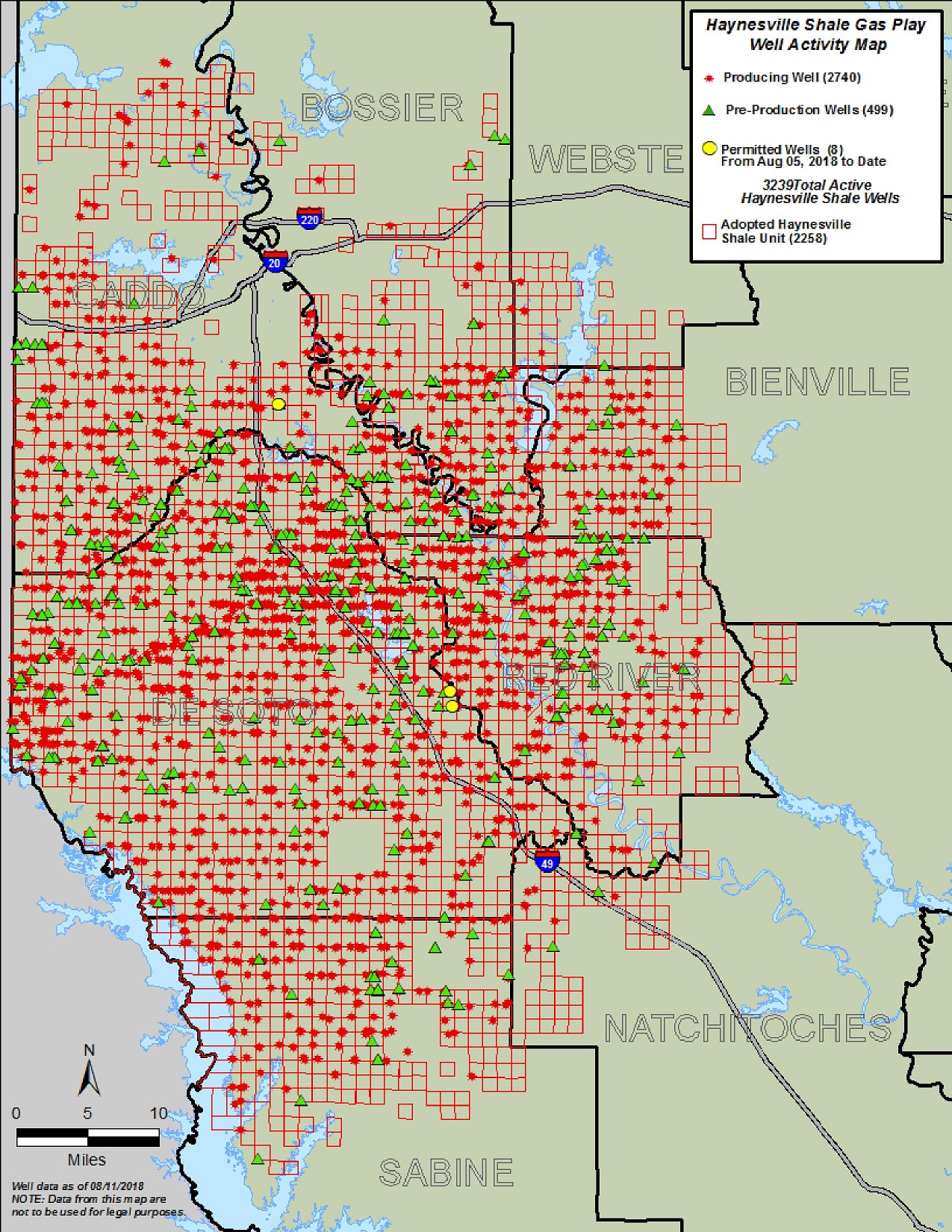

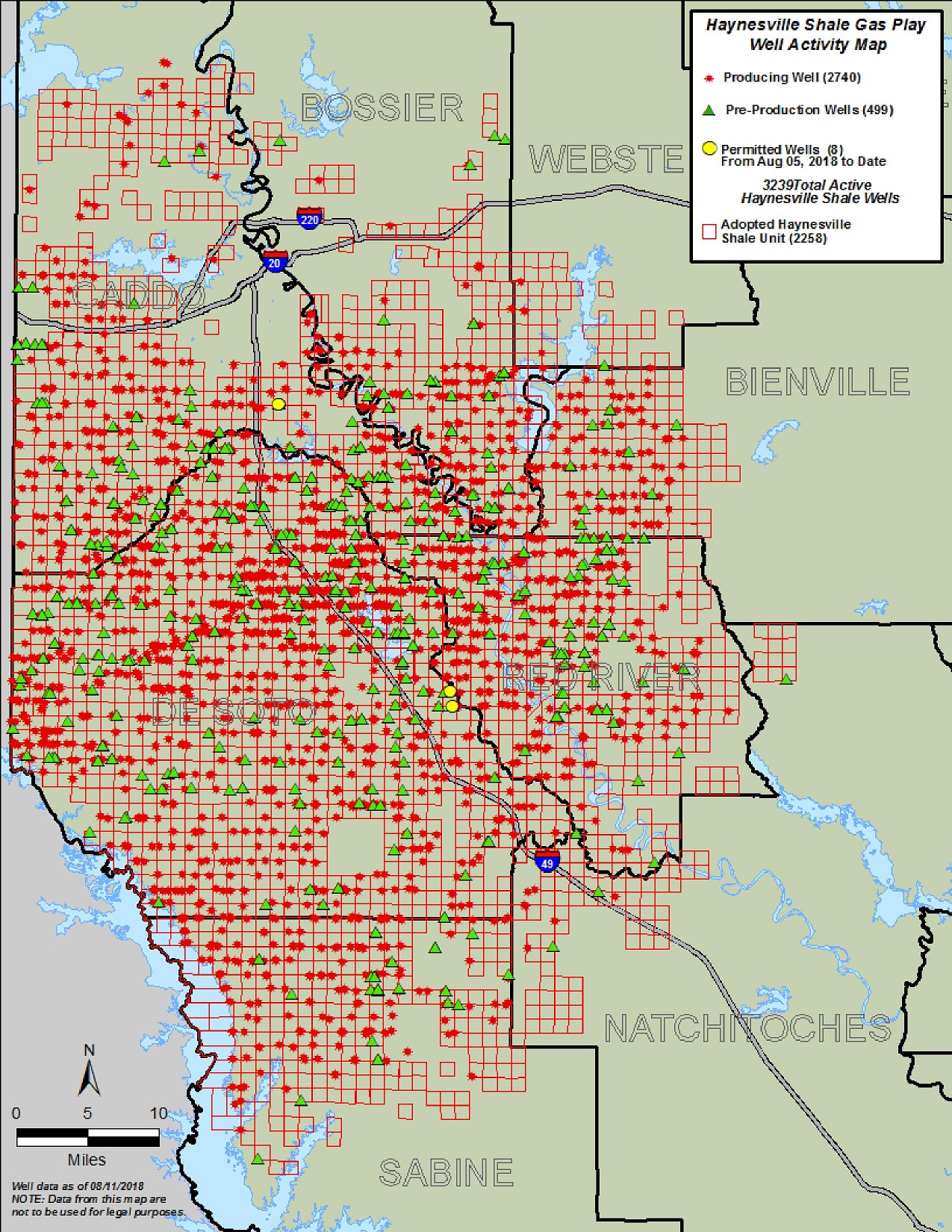

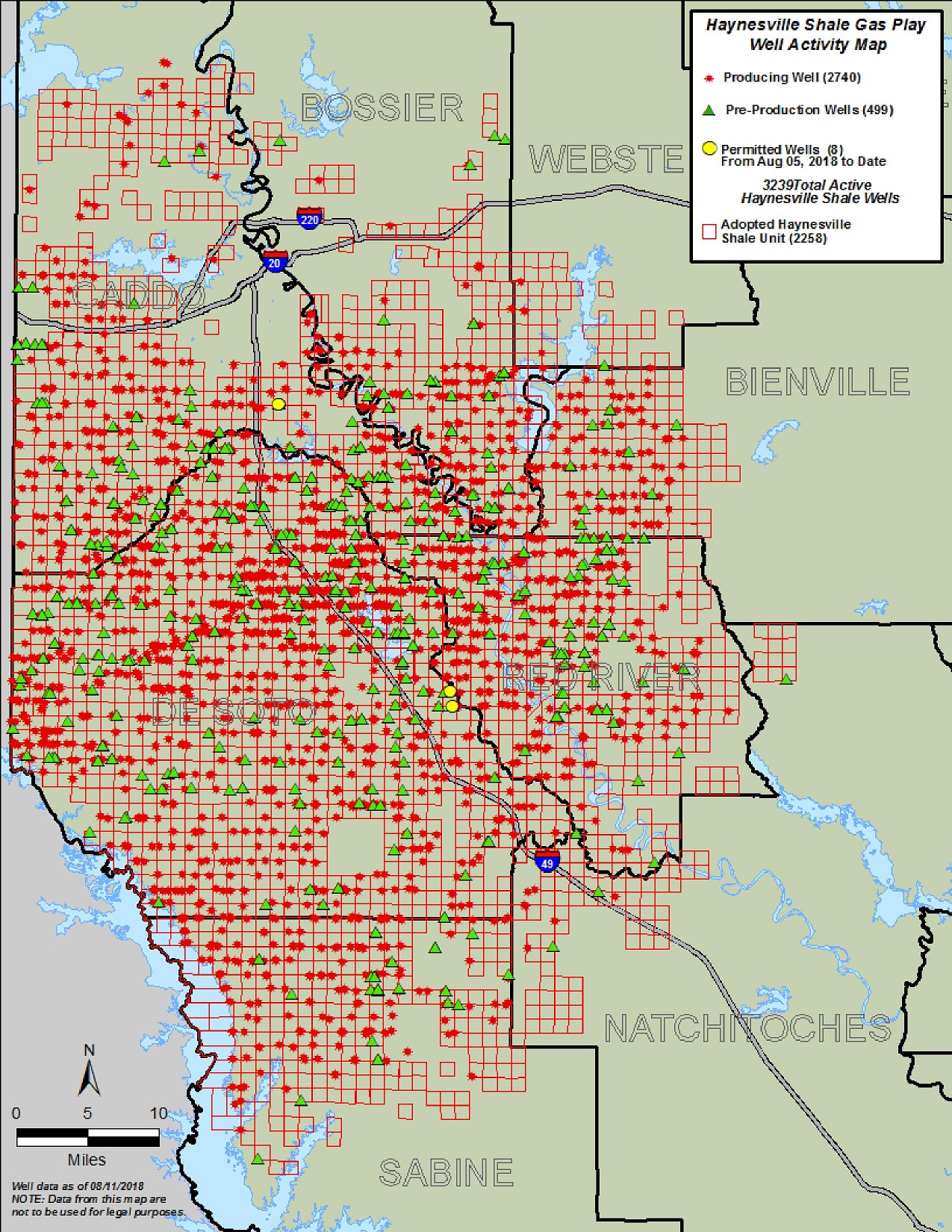

Comeaux confirmed, saying, “Indigo is the most active driller in the Bethany-Longstreet field, with 85 wells currently, and five rigs active.” He added, somewhat uncomfortably, “You could describe their activity as voluminous.”

(Full disclosure: due to inheritance, my husband receives royalties from Indigo Minerals, from a conventional gas well in East Texas.)

In closing, Shealy stated, “Indigo is trying to maximize the development, and these wells are in the interest of conservation. They will drain the gas, and therefore will prevent waste of the natural resource.”

Say what? “Wells are in the interest of conservation”? According to my dictionary, “conservation” is defined as: preservation, protection, or restoration of the natural environment, natural ecosystems, vegetation, and wildlife.

There’s more that’s not quite right than just the language being used.

Indigo Minerals has allegedly been over-pressurizing some of its other DeSoto Parish wells in the Bethany-Longstreet field, resulting in blowouts. When the first happened in 2015, it abnormally pressurized the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer – the source of drinking water for the parish. The response was to “plug” that particular gas well.

This aquifer doesn’t just provide drinking water to DeSoto Parish. Starting in Arkansas, the underground river flows below the northwest corner of our state, and is the source for drinking water in Bossier, Natchitoches, and Sabine parishes, as well. It then cuts diagonally beneath Texas, from northeast to southwest, meeting the Texas-Mexico border at the Rio Grande River, north of Laredo. Sixty Texas counties rely on the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer for their drinking water, as well.

And in 2017, more water wells in the Bethany-Longstreet area of DeSoto Parish began to blow, sending up geysers of saltwater, oil, gases, sand, and a wide range of chemicals consistent with the known components of fracking fluid. Including a blowout this year, to date a dozen water wells have been rendered unusable, according to a lawsuit filed in state court in June of this year.

Among the gases listed in the suit is hydrogen sulfide. Poisonous, corrosive and flammable, it’s also know as “rotten egg gas”, for its distinctive smell. Unfortunately, the gas quickly deadens the sense of smell, and it’s toxic to humans. It’s heavier than air, and can pool in low-lying areas, or accumulate in poorly-ventilated spaces. Depending on the concentration, it can cause death within minutes, or in up to 48 hours.

Following the oil and gas permit hearing, I asked the attorney for the state Office of Conservation, John Adams, about concerns over Indigo Minerals, the current status of the aquifer, water wells, and – in particular – the reports of hydrogen sulfide gas.

“That’s all been resolved,“ he said. “Several years ago, a road crew used hay bales for erosion control. When they were done with them, a local farmer said he would dispose of them. Well he buried them in his trash heap, covering them over with dirt, and forgot about them.

“Now, as you know, there’s natural gas percolating up through the ground in that region all the time, and as it worked its way up through the decomposing hay bales, it gave off hydrogen sulfide gas. We tracked that down, dug up the rotting hay, and disposed of it properly,” Adams continued. “Problem solved.”

It sounded pretty far-fetched to me, but OSHA.gov does say that “Hydrogen sulfide gas can be produced by the breakdown of organic matter and human/ animal wastes (e.g., sewage).” And while I’m no expert in chemistry, I do know someone who is. I reached out to chemistry professor Dr. Brian Salvatore, department Chair for Physics and Chemistry at LSU-Shreveport.

“It’s remotely possible,” he said, “But highly unlikely.”

Something here stinks worse than rotten-egg gas.

The problem was, the well – serial number 250498, and known familiarly as “Indigo White 1”, ended up somewhere it wasn’t supposed to be. The tail end of the well was nearly a hundred feet closer to the wellhead of a pre-existing fracked well than it was supposed to be.

“The issue today is that Indigo White is 247 feet from Churchman H36, instead of the 330 feet that was as permitted,” DNR’s Todd Keating, who was presiding over the hearing, said disapprovingly.

“200 feet from the center internal is the standard,” Shealey said, defending the error. “If we hadn’t done this, the available hydrocarbons would have otherwise been abandoned. Besides, this is all 16-thousand feet deep.”

Dave Comeaux, a geologist retained by Indigo as an expert witness, acknowledged the Indigo White well is successfully producing about 16000 mcfs of natural gas per day since the initial frack in April.

“As of the end of June, the well had produced more than a billion cubic feet of gas,” Comeaux testified.

Besides, Shealy argued, the Churchman well (also operated by Indigo) had been “shut in” – stopping the pumping of pressurized fracking fluid into the well – in January, while drilling and placement of reinforced pipe was completed on the White well.

Comeaux explained that the drilling company then pulled the pipe and liner from the Churchman well, and set new pipe and liner in it. Indigo fracked the White well, then refracked the Churchman well just days apart.

The hearing officers seemed concerned by the intensity of activity concentrated in one place, and questioned the wisdom of fracking two wells so close together in both time and distance.

Shealy insisted it was both necessary and usual practice.

“It is wise to treat this as one big project, and it’s common to refrack when a nearby well is coming on line – to minimize the pressure differentials,” the lawyer said, adding, “Of course, I can’t elaborate here – it’s a protection matter, you know?”

The hearing officers then asked the geologist if “stimulating converging laterals” was standard practice.

“It might be common,” Comeaux said hesitantly and more than a bit reluctantly. “I don’t know. I do know in this case, it was done without incident.”

Shealy insisted this is the most economical way for the company to operate.

“Indigo considers it necessary to drill the field as essentially one big project,” Shealy said. “We have three wells going out from the White drilling pad, and two wells from the Churchman pad. The cost savings on these five wells is $1.5-million. That’s why Indigo prefers to drill multiple cross unit laterals, keeping our rigs in the field and moving them from pad to pad.”

Comeaux confirmed, saying, “Indigo is the most active driller in the Bethany-Longstreet field, with 85 wells currently, and five rigs active.” He added, somewhat uncomfortably, “You could describe their activity as voluminous.”

(Full disclosure: due to inheritance, my husband receives royalties from Indigo Minerals, from a conventional gas well in East Texas.)

In closing, Shealy stated, “Indigo is trying to maximize the development, and these wells are in the interest of conservation. They will drain the gas, and therefore will prevent waste of the natural resource.”

Say what? “Wells are in the interest of conservation”? According to my dictionary, “conservation” is defined as: preservation, protection, or restoration of the natural environment, natural ecosystems, vegetation, and wildlife.

There’s more that’s not quite right than just the language being used.

Indigo Minerals has allegedly been over-pressurizing some of its other DeSoto Parish wells in the Bethany-Longstreet field, resulting in blowouts. When the first happened in 2015, it abnormally pressurized the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer – the source of drinking water for the parish. The response was to “plug” that particular gas well.

This aquifer doesn’t just provide drinking water to DeSoto Parish. Starting in Arkansas, the underground river flows below the northwest corner of our state, and is the source for drinking water in Bossier, Natchitoches, and Sabine parishes, as well. It then cuts diagonally beneath Texas, from northeast to southwest, meeting the Texas-Mexico border at the Rio Grande River, north of Laredo. Sixty Texas counties rely on the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer for their drinking water, as well.

And in 2017, more water wells in the Bethany-Longstreet area of DeSoto Parish began to blow, sending up geysers of saltwater, oil, gases, sand, and a wide range of chemicals consistent with the known components of fracking fluid. Including a blowout this year, to date a dozen water wells have been rendered unusable, according to a lawsuit filed in state court in June of this year.

Among the gases listed in the suit is hydrogen sulfide. Poisonous, corrosive and flammable, it’s also know as “rotten egg gas”, for its distinctive smell. Unfortunately, the gas quickly deadens the sense of smell, and it’s toxic to humans. It’s heavier than air, and can pool in low-lying areas, or accumulate in poorly-ventilated spaces. Depending on the concentration, it can cause death within minutes, or in up to 48 hours.

Following the oil and gas permit hearing, I asked the attorney for the state Office of Conservation, John Adams, about concerns over Indigo Minerals, the current status of the aquifer, water wells, and – in particular – the reports of hydrogen sulfide gas.

“That’s all been resolved,“ he said. “Several years ago, a road crew used hay bales for erosion control. When they were done with them, a local farmer said he would dispose of them. Well he buried them in his trash heap, covering them over with dirt, and forgot about them.

“Now, as you know, there’s natural gas percolating up through the ground in that region all the time, and as it worked its way up through the decomposing hay bales, it gave off hydrogen sulfide gas. We tracked that down, dug up the rotting hay, and disposed of it properly,” Adams continued. “Problem solved.”

It sounded pretty far-fetched to me, but OSHA.gov does say that “Hydrogen sulfide gas can be produced by the breakdown of organic matter and human/ animal wastes (e.g., sewage).” And while I’m no expert in chemistry, I do know someone who is. I reached out to chemistry professor Dr. Brian Salvatore, department Chair for Physics and Chemistry at LSU-Shreveport.

“It’s remotely possible,” he said, “But highly unlikely.”

Something here stinks worse than rotten-egg gas. Drill, Baby, Drill!

[aesop_collection collection=”510″ limit=”6″ columns=”2″ splash=”off” order=”default” loadmore=”off” showexcerpt=”on” revealfx=”off”]

[dropcap]“[/dropcap][dropcap]T[/dropcap]his well was a success, and our clients are happy with the money they’re making, and the revenue they’re generating,” attorney Jeremy Shealy told Louisiana Department of Natural Resources hearing officers on Tuesday morning.

It was a regularly scheduled public hearing before the agency that oversees oil and gas wells in the state, and Shealy was representing Indigo Minerals LLC to certify their completion of a new horizontal gas well in DeSoto Parish’s Bethany-Longstreet field.

The problem was, the well – serial number 250498, and known familiarly as “Indigo White 1”, ended up somewhere it wasn’t supposed to be. The tail end of the well was nearly a hundred feet closer to the wellhead of a pre-existing fracked well than it was supposed to be.

“The issue today is that Indigo White is 247 feet from Churchman H36, instead of the 330 feet that was as permitted,” DNR’s Todd Keating, who was presiding over the hearing, said disapprovingly.

“200 feet from the center internal is the standard,” Shealey said, defending the error. “If we hadn’t done this, the available hydrocarbons would have otherwise been abandoned. Besides, this is all 16-thousand feet deep.”

Dave Comeaux, a geologist retained by Indigo as an expert witness, acknowledged the Indigo White well is successfully producing about 16000 mcfs of natural gas per day since the initial frack in April.

“As of the end of June, the well had produced more than a billion cubic feet of gas,” Comeaux testified.

Besides, Shealy argued, the Churchman well (also operated by Indigo) had been “shut in” – stopping the pumping of pressurized fracking fluid into the well – in January, while drilling and placement of reinforced pipe was completed on the White well.

Comeaux explained that the drilling company then pulled the pipe and liner from the Churchman well, and set new pipe and liner in it. Indigo fracked the White well, then refracked the Churchman well just days apart.

The hearing officers seemed concerned by the intensity of activity concentrated in one place, and questioned the wisdom of fracking two wells so close together in both time and distance.

Shealy insisted it was both necessary and usual practice.

“It is wise to treat this as one big project, and it’s common to refrack when a nearby well is coming on line – to minimize the pressure differentials,” the lawyer said, adding, “Of course, I can’t elaborate here – it’s a protection matter, you know?”

The hearing officers then asked the geologist if “stimulating converging laterals” was standard practice.

“It might be common,” Comeaux said hesitantly and more than a bit reluctantly. “I don’t know. I do know in this case, it was done without incident.”

Shealy insisted this is the most economical way for the company to operate.

“Indigo considers it necessary to drill the field as essentially one big project,” Shealy said. “We have three wells going out from the White drilling pad, and two wells from the Churchman pad. The cost savings on these five wells is $1.5-million. That’s why Indigo prefers to drill multiple cross unit laterals, keeping our rigs in the field and moving them from pad to pad.”

Comeaux confirmed, saying, “Indigo is the most active driller in the Bethany-Longstreet field, with 85 wells currently, and five rigs active.” He added, somewhat uncomfortably, “You could describe their activity as voluminous.”

(Full disclosure: due to inheritance, my husband receives royalties from Indigo Minerals, from a conventional gas well in East Texas.)

In closing, Shealy stated, “Indigo is trying to maximize the development, and these wells are in the interest of conservation. They will drain the gas, and therefore will prevent waste of the natural resource.”

Say what? “Wells are in the interest of conservation”? According to my dictionary, “conservation” is defined as: preservation, protection, or restoration of the natural environment, natural ecosystems, vegetation, and wildlife.

There’s more that’s not quite right than just the language being used.

Indigo Minerals has allegedly been over-pressurizing some of its other DeSoto Parish wells in the Bethany-Longstreet field, resulting in blowouts. When the first happened in 2015, it abnormally pressurized the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer – the source of drinking water for the parish. The response was to “plug” that particular gas well.

This aquifer doesn’t just provide drinking water to DeSoto Parish. Starting in Arkansas, the underground river flows below the northwest corner of our state, and is the source for drinking water in Bossier, Natchitoches, and Sabine parishes, as well. It then cuts diagonally beneath Texas, from northeast to southwest, meeting the Texas-Mexico border at the Rio Grande River, north of Laredo. Sixty Texas counties rely on the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer for their drinking water, as well.

And in 2017, more water wells in the Bethany-Longstreet area of DeSoto Parish began to blow, sending up geysers of saltwater, oil, gases, sand, and a wide range of chemicals consistent with the known components of fracking fluid. Including a blowout this year, to date a dozen water wells have been rendered unusable, according to a lawsuit filed in state court in June of this year.

Among the gases listed in the suit is hydrogen sulfide. Poisonous, corrosive and flammable, it’s also know as “rotten egg gas”, for its distinctive smell. Unfortunately, the gas quickly deadens the sense of smell, and it’s toxic to humans. It’s heavier than air, and can pool in low-lying areas, or accumulate in poorly-ventilated spaces. Depending on the concentration, it can cause death within minutes, or in up to 48 hours.

Following the oil and gas permit hearing, I asked the attorney for the state Office of Conservation, John Adams, about concerns over Indigo Minerals, the current status of the aquifer, water wells, and – in particular – the reports of hydrogen sulfide gas.

“That’s all been resolved,“ he said. “Several years ago, a road crew used hay bales for erosion control. When they were done with them, a local farmer said he would dispose of them. Well he buried them in his trash heap, covering them over with dirt, and forgot about them.

“Now, as you know, there’s natural gas percolating up through the ground in that region all the time, and as it worked its way up through the decomposing hay bales, it gave off hydrogen sulfide gas. We tracked that down, dug up the rotting hay, and disposed of it properly,” Adams continued. “Problem solved.”

It sounded pretty far-fetched to me, but OSHA.gov does say that “Hydrogen sulfide gas can be produced by the breakdown of organic matter and human/ animal wastes (e.g., sewage).” And while I’m no expert in chemistry, I do know someone who is. I reached out to chemistry professor Dr. Brian Salvatore, department Chair for Physics and Chemistry at LSU-Shreveport.

“It’s remotely possible,” he said, “But highly unlikely.”

Something here stinks worse than rotten-egg gas.

The problem was, the well – serial number 250498, and known familiarly as “Indigo White 1”, ended up somewhere it wasn’t supposed to be. The tail end of the well was nearly a hundred feet closer to the wellhead of a pre-existing fracked well than it was supposed to be.

“The issue today is that Indigo White is 247 feet from Churchman H36, instead of the 330 feet that was as permitted,” DNR’s Todd Keating, who was presiding over the hearing, said disapprovingly.

“200 feet from the center internal is the standard,” Shealey said, defending the error. “If we hadn’t done this, the available hydrocarbons would have otherwise been abandoned. Besides, this is all 16-thousand feet deep.”

Dave Comeaux, a geologist retained by Indigo as an expert witness, acknowledged the Indigo White well is successfully producing about 16000 mcfs of natural gas per day since the initial frack in April.

“As of the end of June, the well had produced more than a billion cubic feet of gas,” Comeaux testified.

Besides, Shealy argued, the Churchman well (also operated by Indigo) had been “shut in” – stopping the pumping of pressurized fracking fluid into the well – in January, while drilling and placement of reinforced pipe was completed on the White well.

Comeaux explained that the drilling company then pulled the pipe and liner from the Churchman well, and set new pipe and liner in it. Indigo fracked the White well, then refracked the Churchman well just days apart.

The hearing officers seemed concerned by the intensity of activity concentrated in one place, and questioned the wisdom of fracking two wells so close together in both time and distance.

Shealy insisted it was both necessary and usual practice.

“It is wise to treat this as one big project, and it’s common to refrack when a nearby well is coming on line – to minimize the pressure differentials,” the lawyer said, adding, “Of course, I can’t elaborate here – it’s a protection matter, you know?”

The hearing officers then asked the geologist if “stimulating converging laterals” was standard practice.

“It might be common,” Comeaux said hesitantly and more than a bit reluctantly. “I don’t know. I do know in this case, it was done without incident.”

Shealy insisted this is the most economical way for the company to operate.

“Indigo considers it necessary to drill the field as essentially one big project,” Shealy said. “We have three wells going out from the White drilling pad, and two wells from the Churchman pad. The cost savings on these five wells is $1.5-million. That’s why Indigo prefers to drill multiple cross unit laterals, keeping our rigs in the field and moving them from pad to pad.”

Comeaux confirmed, saying, “Indigo is the most active driller in the Bethany-Longstreet field, with 85 wells currently, and five rigs active.” He added, somewhat uncomfortably, “You could describe their activity as voluminous.”

(Full disclosure: due to inheritance, my husband receives royalties from Indigo Minerals, from a conventional gas well in East Texas.)

In closing, Shealy stated, “Indigo is trying to maximize the development, and these wells are in the interest of conservation. They will drain the gas, and therefore will prevent waste of the natural resource.”

Say what? “Wells are in the interest of conservation”? According to my dictionary, “conservation” is defined as: preservation, protection, or restoration of the natural environment, natural ecosystems, vegetation, and wildlife.

There’s more that’s not quite right than just the language being used.

Indigo Minerals has allegedly been over-pressurizing some of its other DeSoto Parish wells in the Bethany-Longstreet field, resulting in blowouts. When the first happened in 2015, it abnormally pressurized the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer – the source of drinking water for the parish. The response was to “plug” that particular gas well.

This aquifer doesn’t just provide drinking water to DeSoto Parish. Starting in Arkansas, the underground river flows below the northwest corner of our state, and is the source for drinking water in Bossier, Natchitoches, and Sabine parishes, as well. It then cuts diagonally beneath Texas, from northeast to southwest, meeting the Texas-Mexico border at the Rio Grande River, north of Laredo. Sixty Texas counties rely on the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer for their drinking water, as well.

And in 2017, more water wells in the Bethany-Longstreet area of DeSoto Parish began to blow, sending up geysers of saltwater, oil, gases, sand, and a wide range of chemicals consistent with the known components of fracking fluid. Including a blowout this year, to date a dozen water wells have been rendered unusable, according to a lawsuit filed in state court in June of this year.

Among the gases listed in the suit is hydrogen sulfide. Poisonous, corrosive and flammable, it’s also know as “rotten egg gas”, for its distinctive smell. Unfortunately, the gas quickly deadens the sense of smell, and it’s toxic to humans. It’s heavier than air, and can pool in low-lying areas, or accumulate in poorly-ventilated spaces. Depending on the concentration, it can cause death within minutes, or in up to 48 hours.

Following the oil and gas permit hearing, I asked the attorney for the state Office of Conservation, John Adams, about concerns over Indigo Minerals, the current status of the aquifer, water wells, and – in particular – the reports of hydrogen sulfide gas.

“That’s all been resolved,“ he said. “Several years ago, a road crew used hay bales for erosion control. When they were done with them, a local farmer said he would dispose of them. Well he buried them in his trash heap, covering them over with dirt, and forgot about them.

“Now, as you know, there’s natural gas percolating up through the ground in that region all the time, and as it worked its way up through the decomposing hay bales, it gave off hydrogen sulfide gas. We tracked that down, dug up the rotting hay, and disposed of it properly,” Adams continued. “Problem solved.”

It sounded pretty far-fetched to me, but OSHA.gov does say that “Hydrogen sulfide gas can be produced by the breakdown of organic matter and human/ animal wastes (e.g., sewage).” And while I’m no expert in chemistry, I do know someone who is. I reached out to chemistry professor Dr. Brian Salvatore, department Chair for Physics and Chemistry at LSU-Shreveport.

“It’s remotely possible,” he said, “But highly unlikely.”

Something here stinks worse than rotten-egg gas.

The problem was, the well – serial number 250498, and known familiarly as “Indigo White 1”, ended up somewhere it wasn’t supposed to be. The tail end of the well was nearly a hundred feet closer to the wellhead of a pre-existing fracked well than it was supposed to be.

“The issue today is that Indigo White is 247 feet from Churchman H36, instead of the 330 feet that was as permitted,” DNR’s Todd Keating, who was presiding over the hearing, said disapprovingly.

“200 feet from the center internal is the standard,” Shealey said, defending the error. “If we hadn’t done this, the available hydrocarbons would have otherwise been abandoned. Besides, this is all 16-thousand feet deep.”

Dave Comeaux, a geologist retained by Indigo as an expert witness, acknowledged the Indigo White well is successfully producing about 16000 mcfs of natural gas per day since the initial frack in April.

“As of the end of June, the well had produced more than a billion cubic feet of gas,” Comeaux testified.

Besides, Shealy argued, the Churchman well (also operated by Indigo) had been “shut in” – stopping the pumping of pressurized fracking fluid into the well – in January, while drilling and placement of reinforced pipe was completed on the White well.

Comeaux explained that the drilling company then pulled the pipe and liner from the Churchman well, and set new pipe and liner in it. Indigo fracked the White well, then refracked the Churchman well just days apart.

The hearing officers seemed concerned by the intensity of activity concentrated in one place, and questioned the wisdom of fracking two wells so close together in both time and distance.

Shealy insisted it was both necessary and usual practice.

“It is wise to treat this as one big project, and it’s common to refrack when a nearby well is coming on line – to minimize the pressure differentials,” the lawyer said, adding, “Of course, I can’t elaborate here – it’s a protection matter, you know?”

The hearing officers then asked the geologist if “stimulating converging laterals” was standard practice.

“It might be common,” Comeaux said hesitantly and more than a bit reluctantly. “I don’t know. I do know in this case, it was done without incident.”

Shealy insisted this is the most economical way for the company to operate.

“Indigo considers it necessary to drill the field as essentially one big project,” Shealy said. “We have three wells going out from the White drilling pad, and two wells from the Churchman pad. The cost savings on these five wells is $1.5-million. That’s why Indigo prefers to drill multiple cross unit laterals, keeping our rigs in the field and moving them from pad to pad.”

Comeaux confirmed, saying, “Indigo is the most active driller in the Bethany-Longstreet field, with 85 wells currently, and five rigs active.” He added, somewhat uncomfortably, “You could describe their activity as voluminous.”

(Full disclosure: due to inheritance, my husband receives royalties from Indigo Minerals, from a conventional gas well in East Texas.)

In closing, Shealy stated, “Indigo is trying to maximize the development, and these wells are in the interest of conservation. They will drain the gas, and therefore will prevent waste of the natural resource.”

Say what? “Wells are in the interest of conservation”? According to my dictionary, “conservation” is defined as: preservation, protection, or restoration of the natural environment, natural ecosystems, vegetation, and wildlife.

There’s more that’s not quite right than just the language being used.

Indigo Minerals has allegedly been over-pressurizing some of its other DeSoto Parish wells in the Bethany-Longstreet field, resulting in blowouts. When the first happened in 2015, it abnormally pressurized the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer – the source of drinking water for the parish. The response was to “plug” that particular gas well.

This aquifer doesn’t just provide drinking water to DeSoto Parish. Starting in Arkansas, the underground river flows below the northwest corner of our state, and is the source for drinking water in Bossier, Natchitoches, and Sabine parishes, as well. It then cuts diagonally beneath Texas, from northeast to southwest, meeting the Texas-Mexico border at the Rio Grande River, north of Laredo. Sixty Texas counties rely on the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer for their drinking water, as well.

And in 2017, more water wells in the Bethany-Longstreet area of DeSoto Parish began to blow, sending up geysers of saltwater, oil, gases, sand, and a wide range of chemicals consistent with the known components of fracking fluid. Including a blowout this year, to date a dozen water wells have been rendered unusable, according to a lawsuit filed in state court in June of this year.

Among the gases listed in the suit is hydrogen sulfide. Poisonous, corrosive and flammable, it’s also know as “rotten egg gas”, for its distinctive smell. Unfortunately, the gas quickly deadens the sense of smell, and it’s toxic to humans. It’s heavier than air, and can pool in low-lying areas, or accumulate in poorly-ventilated spaces. Depending on the concentration, it can cause death within minutes, or in up to 48 hours.

Following the oil and gas permit hearing, I asked the attorney for the state Office of Conservation, John Adams, about concerns over Indigo Minerals, the current status of the aquifer, water wells, and – in particular – the reports of hydrogen sulfide gas.

“That’s all been resolved,“ he said. “Several years ago, a road crew used hay bales for erosion control. When they were done with them, a local farmer said he would dispose of them. Well he buried them in his trash heap, covering them over with dirt, and forgot about them.

“Now, as you know, there’s natural gas percolating up through the ground in that region all the time, and as it worked its way up through the decomposing hay bales, it gave off hydrogen sulfide gas. We tracked that down, dug up the rotting hay, and disposed of it properly,” Adams continued. “Problem solved.”

It sounded pretty far-fetched to me, but OSHA.gov does say that “Hydrogen sulfide gas can be produced by the breakdown of organic matter and human/ animal wastes (e.g., sewage).” And while I’m no expert in chemistry, I do know someone who is. I reached out to chemistry professor Dr. Brian Salvatore, department Chair for Physics and Chemistry at LSU-Shreveport.

“It’s remotely possible,” he said, “But highly unlikely.”

Something here stinks worse than rotten-egg gas.

The problem was, the well – serial number 250498, and known familiarly as “Indigo White 1”, ended up somewhere it wasn’t supposed to be. The tail end of the well was nearly a hundred feet closer to the wellhead of a pre-existing fracked well than it was supposed to be.

“The issue today is that Indigo White is 247 feet from Churchman H36, instead of the 330 feet that was as permitted,” DNR’s Todd Keating, who was presiding over the hearing, said disapprovingly.

“200 feet from the center internal is the standard,” Shealey said, defending the error. “If we hadn’t done this, the available hydrocarbons would have otherwise been abandoned. Besides, this is all 16-thousand feet deep.”

Dave Comeaux, a geologist retained by Indigo as an expert witness, acknowledged the Indigo White well is successfully producing about 16000 mcfs of natural gas per day since the initial frack in April.

“As of the end of June, the well had produced more than a billion cubic feet of gas,” Comeaux testified.

Besides, Shealy argued, the Churchman well (also operated by Indigo) had been “shut in” – stopping the pumping of pressurized fracking fluid into the well – in January, while drilling and placement of reinforced pipe was completed on the White well.

Comeaux explained that the drilling company then pulled the pipe and liner from the Churchman well, and set new pipe and liner in it. Indigo fracked the White well, then refracked the Churchman well just days apart.

The hearing officers seemed concerned by the intensity of activity concentrated in one place, and questioned the wisdom of fracking two wells so close together in both time and distance.

Shealy insisted it was both necessary and usual practice.

“It is wise to treat this as one big project, and it’s common to refrack when a nearby well is coming on line – to minimize the pressure differentials,” the lawyer said, adding, “Of course, I can’t elaborate here – it’s a protection matter, you know?”

The hearing officers then asked the geologist if “stimulating converging laterals” was standard practice.

“It might be common,” Comeaux said hesitantly and more than a bit reluctantly. “I don’t know. I do know in this case, it was done without incident.”

Shealy insisted this is the most economical way for the company to operate.

“Indigo considers it necessary to drill the field as essentially one big project,” Shealy said. “We have three wells going out from the White drilling pad, and two wells from the Churchman pad. The cost savings on these five wells is $1.5-million. That’s why Indigo prefers to drill multiple cross unit laterals, keeping our rigs in the field and moving them from pad to pad.”

Comeaux confirmed, saying, “Indigo is the most active driller in the Bethany-Longstreet field, with 85 wells currently, and five rigs active.” He added, somewhat uncomfortably, “You could describe their activity as voluminous.”

(Full disclosure: due to inheritance, my husband receives royalties from Indigo Minerals, from a conventional gas well in East Texas.)

In closing, Shealy stated, “Indigo is trying to maximize the development, and these wells are in the interest of conservation. They will drain the gas, and therefore will prevent waste of the natural resource.”

Say what? “Wells are in the interest of conservation”? According to my dictionary, “conservation” is defined as: preservation, protection, or restoration of the natural environment, natural ecosystems, vegetation, and wildlife.

There’s more that’s not quite right than just the language being used.

Indigo Minerals has allegedly been over-pressurizing some of its other DeSoto Parish wells in the Bethany-Longstreet field, resulting in blowouts. When the first happened in 2015, it abnormally pressurized the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer – the source of drinking water for the parish. The response was to “plug” that particular gas well.

This aquifer doesn’t just provide drinking water to DeSoto Parish. Starting in Arkansas, the underground river flows below the northwest corner of our state, and is the source for drinking water in Bossier, Natchitoches, and Sabine parishes, as well. It then cuts diagonally beneath Texas, from northeast to southwest, meeting the Texas-Mexico border at the Rio Grande River, north of Laredo. Sixty Texas counties rely on the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer for their drinking water, as well.

And in 2017, more water wells in the Bethany-Longstreet area of DeSoto Parish began to blow, sending up geysers of saltwater, oil, gases, sand, and a wide range of chemicals consistent with the known components of fracking fluid. Including a blowout this year, to date a dozen water wells have been rendered unusable, according to a lawsuit filed in state court in June of this year.

Among the gases listed in the suit is hydrogen sulfide. Poisonous, corrosive and flammable, it’s also know as “rotten egg gas”, for its distinctive smell. Unfortunately, the gas quickly deadens the sense of smell, and it’s toxic to humans. It’s heavier than air, and can pool in low-lying areas, or accumulate in poorly-ventilated spaces. Depending on the concentration, it can cause death within minutes, or in up to 48 hours.

Following the oil and gas permit hearing, I asked the attorney for the state Office of Conservation, John Adams, about concerns over Indigo Minerals, the current status of the aquifer, water wells, and – in particular – the reports of hydrogen sulfide gas.

“That’s all been resolved,“ he said. “Several years ago, a road crew used hay bales for erosion control. When they were done with them, a local farmer said he would dispose of them. Well he buried them in his trash heap, covering them over with dirt, and forgot about them.

“Now, as you know, there’s natural gas percolating up through the ground in that region all the time, and as it worked its way up through the decomposing hay bales, it gave off hydrogen sulfide gas. We tracked that down, dug up the rotting hay, and disposed of it properly,” Adams continued. “Problem solved.”

It sounded pretty far-fetched to me, but OSHA.gov does say that “Hydrogen sulfide gas can be produced by the breakdown of organic matter and human/ animal wastes (e.g., sewage).” And while I’m no expert in chemistry, I do know someone who is. I reached out to chemistry professor Dr. Brian Salvatore, department Chair for Physics and Chemistry at LSU-Shreveport.

“It’s remotely possible,” he said, “But highly unlikely.”

Something here stinks worse than rotten-egg gas.