On Sept. 4, 2018, with bulldozers revving their engines in accompaniment, Cherri Foytlin was tackled and placed in a choke hold by a non-uniformed man who then knelt atop her, grinding her into the sticky mud of the Atchafalaya Basin.

Two uniformed deputies then moved in to provide handcuffs and escort the environmental activist off to the St. Martin Parish jail. She was charged with “criminal damage to critical infrastructure” – in this case, blocking work on the Bayou Bridge pipeline by protesting.

Over the previous month, some dozen individuals, including a reporter covering the protests, had been tackled, tased, arrested, and charged under the same law – Act 692, which went into effect Aug. 1, 2018.

The day before Foytlin’s arrest, fifty people had – at that same spot — been able to halt work on the muddy strip in St. Martin Parish. All were there at the invitation of the property owner, who has refused to agree to the sale or use of the property for the pipeline. He is being sued by the pipeline’s parent company, Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), to force him to surrender the right-of-way.

From the time we’re very young, we’re taught about the superiority of our democracy. We’re proud of our Bill of Rights and of our First Amendment’s guaranteed freedom of speech.

Here in Louisiana, our state Constitution opens with a paean to democracy: “All government, of right, originates with the people, is founded on their will alone, and is instituted to protect the rights of the individual and for the good of the whole.”

Due process, the Right to Individual Dignity, and the Right to Property (more on that later) immediately follow that statement. After that comes the Right to Privacy, Freedom from Intrusion, and finally – in section 7, Freedom of Expression, which states: “No law shall curtail or restrain freedom of speech of of the press.”

Yet as events and actions surrounding the Bayou Bridge opposition illustrate, our individual and community rights are far from “inalienable” – in actual practice.

The U.S. Constitution, enacted 231 years ago this week, was designed “to facilitate commerce.” And while the (overused) mantra of innovation and improvement has become “thinking outside the box,” the last things corporate interests want citizens doing – especially when it comes to protecting the environment – is anything “outside the box.”

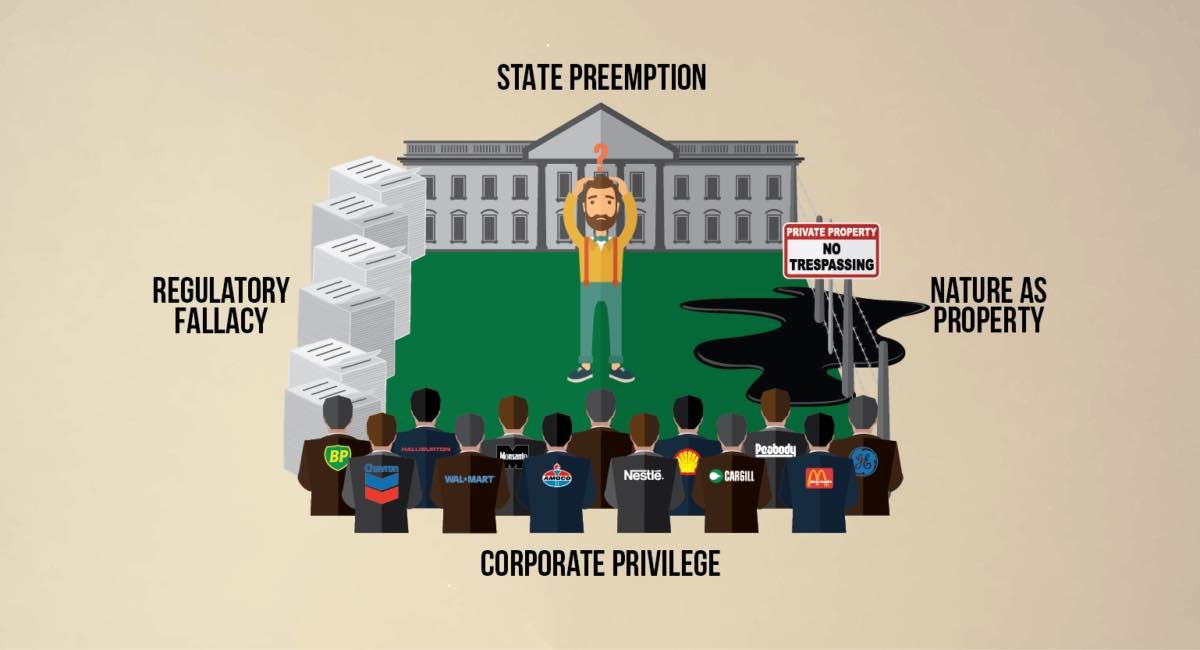

The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), a national nonprofit organization that “provides legal services, organizing support, and education to community groups, elected officials, and the general public,” defines the framework. They call it “the Box of Allowable Activism,” and it’s designed to protect corporate interests while also limiting individual rights.

The box has four walls, including the legal view of nature as property. There’s the regulatory fallacy, corporate privilege, and state preemption.

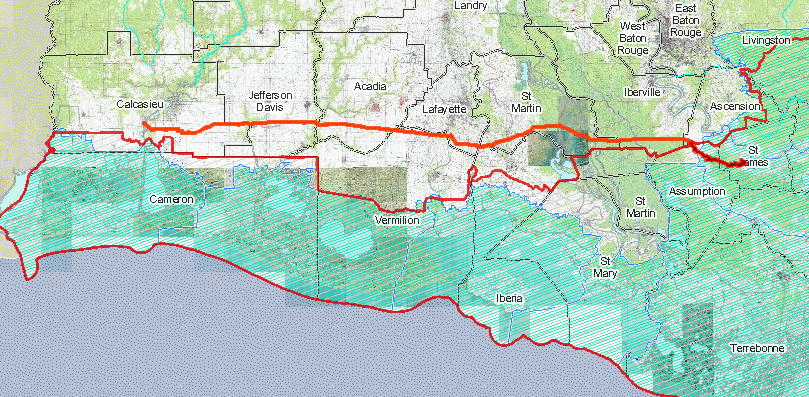

The Bayou Bridge Pipeline is a 163-mile-long conduit for crude oil, being constructed from Lake Charles, Louisiana, to St. James, Louisiana. The $670-million project crosses eleven parishes and eight watersheds, which include more than 600 discrete bodies of water and the ecologically sensitive Atchafalaya Swamp.

It is a cooperative endeavor of Phillips 66, Energy Transfer Partners, and Sunoco (an ETP subsidiary). It links with ETP’s Dakota Access Pipeline through a hub in Nederland, Texas. The pipeline between Nederland and Lake Charles is already complete.

I first met Cherri Foytlin in mid-October 2017.

She was standing in the field across from the Governor’s Mansion, holding a sign that said, “Governor Edwards, we want an Environmental Impact Statement for Bayou Bridge Pipeline.” Accompanied by members of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, 350.org, and others, Foytlin led the group in chants and sign-waving, urging the governor to request an environmental study from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which was considering the pipeline permit at the time.

Louisiana’s Department of Natural Resources had already approved the project.

Noting ETP’s record of pipeline spills and a Phillips 66 pipeline fire in Paradis, LA, which had killed one worker and injured five others earlier that year, Foytlin suggested that while waiting on the Corps’ environmental study, the state could be encouraging the companies to actually follow the rules.

“We have actually really good laws on the books. It’s just this state doesn’t tend to hold companies accountable to do what they’re supposed to do,” Foytlin said. “I don’t think it’s too much to ask that this industry – but in particular this company – cleans up its mess in the first place before they’re allowed to do another project. I mean, I would make my kids clean up before they get more toys out, right?”

But the environmental study wasn’t requested or done, and in Dec. 2017, the Corps approved the Bayou Bridge permit. The next month, a coalition of environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, the Gulf Restoration Network, and Atchafalaya Basinkeepers, with assistance from Earthjustice and the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, filed suit in federal court, seeking an injunction to halt the pipeline construction across the Atchafalaya Basin until an environmental impact study could be done. It was granted, but subsequently appealed by the Corps and Bayou Bridge.

In June, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the lower court’s decision, suggesting that because the Corps had discussed mitigation measures during the permitting process and acknowledged potential environmental impacts, including “permanent loss of wetlands, loss of wildlife habitat, and impacts to water quality,” that was sufficient enough. It may have not been an environmental impact study, but it was an environmental impact statement. Therefore, the formalities have been observed, and it’s okay to build.

With this single decision, the 5th Circuit exposes the lie at the center of the regulatory fallacy.

We’re led to believe that laws like the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act- and the agencies that enforce them – such as the EPA, DEQ, Corps of Engineers, DNR – are there to protect public health and the environment. But the very nature of the regulatory schemes and permitting processes assumes there will be harm.

As one current TV commercial for a water filtration system sarcastically points out, there’s lead in the water, “but it’s well within the allowable standards.” The regulatory system may limit the allowable harm, but it’s still permissible. There is no place in the system for no harm at all.

Why? Because our laws treat nature as property. We buy and sell land and what is on it and underneath it, including the mineral rights that descend – theoretically – all the way down to the earth’s core. If you own it, you have the right to use it and destroy it, if you so choose.

This concept of “property rights” is the basis for another way the Bayou Bridge opponents are endeavoring to halt the project through the state courts. Yet it’s an effort that’s complicated by those another wall in the box of allowable activism: corporate privilege.

Opponents have also been challenging the pipeline in multiple jurisdictions of state court, using a variety of avenues of legal attack.

In St. James Parish, the planned terminus of Bayou Bridge, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, L’Eau Est La Vie, Atchafalaya Basinkeepers, and other objectors argued the state Department of Natural Resources did not exercise “due diligence” in granting the pipeline’s permit because it failed to develop an emergency plan for evacuations in the event of a catastrophe.

The court concurred, ordering the permit back to DNR for reconsideration and and issuing a halt to the work on that segment of the pipeline. ETP appealed, and got the work stoppage lifted while the case itself continued through the court system. (The state’s Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal hears that case on Sept. 19 in Gretna).

It may seem like basic commonsense to demand emergency contingency plans, but to those in the industry, it’s bad optics and bad for business to call the public’s attention to the inherent risks involved.

As we reported in March, Jeff Landry, Louisiana’s state attorney general, is currently leading an effort to prevent the petrochemical industry from complying with the requirement they coordinate disaster response plans with local law enforcement.

Landry, doing the bidding for the industry, argued this was “even more burdensome, duplicative, and needless regulation.”

That’s part of the wall of corporate privilege.

In January of this year, opponents of the Bayou Bridge filed suit in the 19th JDC in Baton Rouge, challenging the pipeline company’s use of eminent domain (or expropriation) to acquire the right-of-way for the pipeline project.

“They are using the power of the state in claiming eminent domain,” Louisiana Bucket Brigade leader Ann Rolfes said. “They are a for-profit private company that is assuming a state function.”

“People who own land along the pipeline route are told, ‘You don’t want us to take your land? We’ll take it through the court system. We’ll take it away from you’,” stated Foytlin, who, as owner of a camp along the pipeline route, is a party to the action. “Most land in the area went for $10 an easement. How many billions and trillions of dollars are going to run underneath that land?”

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s controversial 2005 Kelo v. New London decision, which permitted use of eminent domain for economic development purposes, outraged Louisiana legislators advanced a state constitutional amendment – approved by voters in 2006 – prohibiting state and local governments from taking private property unless it is for a “general public right to a definite use of the property” or the removal of a threat to public health or safety. The amendment defines specific public uses.

Privately operated pipelines are not one of the defined public uses.

That case is still pending, and in July, with their self-set October deadline for pipeline completion fast approaching, ETP filed suit in state court in St. Martin Parish. They’re seeking to force several hundred property owners to surrender their land in the Atchafalaya Swamp. Some of the approximately 700 co-owners of the 38-acre tract have agreed to the pipeline crossing. Others have steadfastly refused, instead giving anti-pipeline activists permission to occupy the property.

On Monday, Sept. 10, as dawn was just beginning to lighten the sky, a pipeline in Center Township, Pennsylvania – 20 miles northeast of Pittsburgh – exploded, knocking down powerlines and towers, closing I-376 and schools across the Central Valley District. More than thirty homes were evacuated; the fire raged for more than two hours.

That pipeline is owned and operated by Energy Transfer Partners.

Just as Pennsylvania authorities were getting that fire under control, a hearing convened on the expropriation matter in Louisiana’s district court in St. Martin Parish. Resistant property owners had countersued ETP, seeing an injunction to halt the bulldozing and trenching in progress across their property.

Somewhat surprisingly, lawyers for the pipeline company agreed to halt work across that tract, until the full trial on the expropriation is conducted in November. That same day, in an email to media, the company said the project would be completed in October. This week, the company has told the media the timeline for completion is now “before the end of this year.”

Pipeline opponents view this as evidence their pushback against the project is working. But a spokeswoman for the company says their finish date is being pushed back as a result of weather conditions.

Beyond all the courtroom wranglings over Bayou Bridge, opponents have long anticipated their efforts to halt the pipeline would also necessitate direct action. They were able to thwart ETP’s plans to use the company TigerSwan for security along the Louisiana pipeline route by presenting examples of that firm’s notorious work for ETP at Standing Rock. The Louisiana Board of Private Security Examiners determined TigerSwan was “unfit” to provide services in this state. Subsequent efforts to set up a “front” company for doing the Louisiana work were similarly uncovered and denied licensing.

Instead, ETP hired three firms — Hilliard Heintze out of Chicago, Athos Group from Irving, Texas, and Hub Enterprises of Lafayette – to do their security work and to surveil and investigate the opponents. Some are off-duty law enforcement officers; others are what are simply unarmed security personnel, often denigratingly referred to as “rent-a-cops.”

Energy Transfer Partners also used its “corporate privilege” to help drive a new law through the Louisiana legislature this past spring. They retained the services of some heavy-hitting lobbyists and coalesced the clout of petrochemical industry groups to push passage of HB 727, now known as Act 692.

While other states – including Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, Wyoming, Ohio, and Colorado – have considered a similar measure to this ALEC (American Legislative Exchange Council) model bill, Louisiana was the only one to fully enact it. The bill designates pipelines as “critical infrastructure,” equivalent to public ports and transportation such as railroads, and public utilities like electric power generating stations and water treatment facilities. The “construction” of pipelines is now included in that definition.

And it makes “unauthorized entry,” also known as trespassing and formerly classified as a misdemeanor, onto the property of one of these facilities a felony, punishable by up to five years in prison. If more than one person is involved in the planning or commission of such an offense, it becomes a “conspiracy,” punishable by up to 12 years and a $250,000 fine.

Even though sections were added to the law declaring it was in no way to apply to “lawful and peaceful assembly or demonstration” or “recreational activities conducted in the open around a pipeline, such as boating” (nor to “prevent the owner of a property form exercising right of ownership, including use”), thirteen people have been arrested and charged with felonies under this law since it went into effect on Aug. 1.

Kayakers and canoeists have been herded ashore, onto the pipeline route, by security in airboats, then handcuffed and carted off to jail.

A reporter covering the action for The Appeal was arrested and charged.

“Tree-sitters,” there at the invitation of property owners refusing to sell out to ETP, had their safety ropes cut. As chainsaws revved up below them, they were forced to scramble down from their perches, and then, they were tased, handcuffed, and hauled away to the lockup.

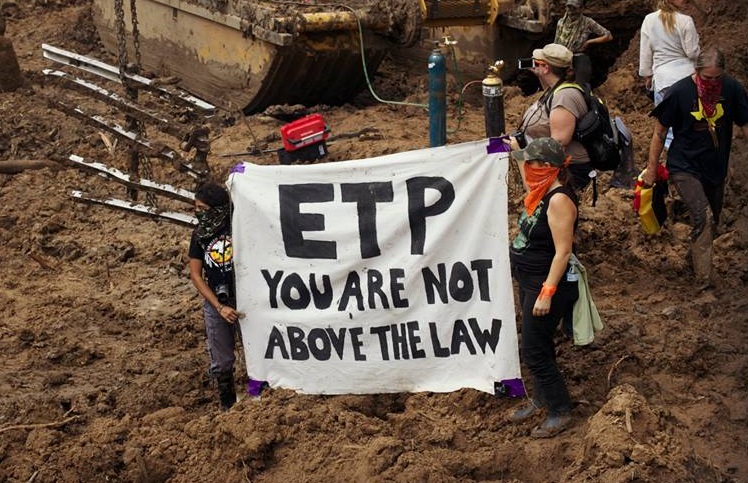

Other objectors, also invited by property owners disputing the pipeline’s right to tear through the land, stood in front of the bulldozers, simply holding a sign saying, “ETP, you are not above the law.”

That’s what Cherri Foytlin was doing when she was tackled and arrested.

Each person arrested had to post a $10,000 bond in order to be released.

As Karen Savage reported in her story for The Appeal, it is difficult to determine under what actual authority these arrests are being conducted. Those doing security for the Bayou Bridge project often wear black ball caps simply stamped with the word “police.” Some are St. Martin Parish deputies, while others have been determined to be state probation and parole officers, moonlighting as Bayou Bridge security.

As a result of media reports on the arrests, the state Department of Public Safety and Corrections has terminated its agreements to provide off-duty officers for Bayou Bridge security details.

But it still appears to be an egregious example of corporate privilege relying on state enforcement, in preemption of individual rights to free speech, assembly, and property rights.

The Center for Constitutional Rights is assisting with defense of those arrested under Act 692, as they fight to retain their freedom from imprisonment and their continued rights to speak out against a project they think is wrong.

ETP claims, conversely, that the environmental protesters are “endangering the very ecosystem they purport to love.”

While the swarm of lawsuits involving the Bayou Bridge Pipeline might seem to be forcing a delay and potentially a halt to the project, the Fortune 500 company undoubtedly considers the environmental groups, property owners, and their various lawsuits to be no more than mosquitoes.

They’ve said they’ll be done with the pipeline by the end of this year. With gross income of $3.69 billion last year alone, they can afford to keep the cases going in court, while continuing work on the pipeline (which was 85% complete as of August) – legal or not. That would effectively render all of the cases moot.

What’s the alternative?

CELDF, which teaches the “Box of Allowable Activism” theory as a cornerstone in its Democracy School, maintains citizen initiative – working to create law to empower “We the People” in lieu of “We the Corporations” – is the answer.

But Louisiana’s constitution has no mechanism for statewide citizen initiative, and local initiative is tightly restricted to those communities that had adopted their Home Rule Charter prior to 1974.

Even with that, our legislators – held in thrall by corporate interests dangling the eternal carrot-and-stick of “jobs” – have consistently used their power to enact state preemption in order to forbid local citizen and governmental initiative on pressing issues.

After the City of New Orleans sued gun manufacturers in 1998 for the costs associated with gun violence, state lawmakers- led by Steve Scalise- passed a law making such action retroactively illegal. And in 2015, they did the same to halt a levee board lawsuit seeking to recover coastal land loss damages from the oil and gas industry.

And while Louisiana citizens currently rank as the nation’s second most-impoverished people, a state law passed in 1997 absolutely prohibits any local governmental subdivision from instituting a minimum wage. In 2012, the legislature added a ban on requiring any employee vacation or sick days, whether paid or unpaid.

All this would tend to lead us into what CELDF calls “the black hole of doubt.” After all, how can mere citizens and their communities possibly scale the walls posed by state preemption and corporate privilege?

But corporate interests, exemplified by the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry (LABI), may end up kicking the activism lockbox door wide open. They have been agitating toward calling a state constitutional convention in order to rewrite Louisiana’s governing document.

In the current political climate, the resurgence of community activism through groups ranging from Together Louisiana to L’Eau Est La Vie could propel such a constitutional convention in an entirely different direction than what’s intended by the corporate gang.

That would be especially ironic for LABI, which was formed to quell the clout of unions – which are, in actuality, a community of individuals with like interests and concerns.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world,” anthropologist Margaret Mead famously stated. “Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”