This week in the New Orleans area, dozens of campaign volunteers huddled in three different nondescript office buildings to phonebank for their favorite candidate of the 2018 midterms.

There weren’t many 318, 337, 225, 985, or 504 area codes on the call lists handed out, and the volunteers can’t actually vote for the candidate they’re supporting because he isn’t on the ballot in Louisiana.

No, they called voters in Texas, in support of U.S. Senate candidate Beto O’Rourke.

“Even Moses got excited when he saw the promised land,” Lyle Lovett croons about his home state. “That’s right. You’re not from Texas. But Texas wants you anyway.”

****

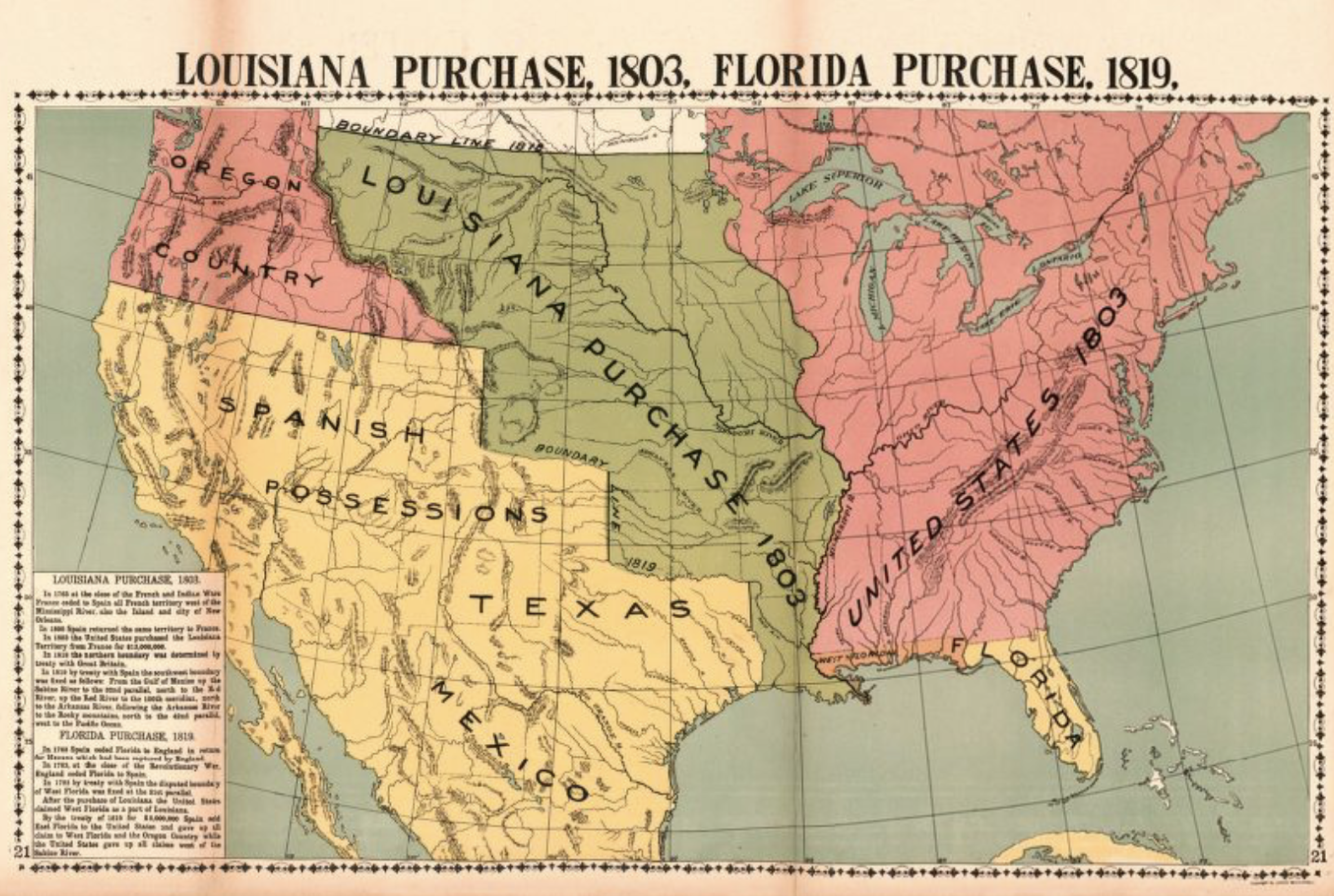

There was a time when the word Louisiana covered nearly half of the country. The Louisiana Purchase included approximately 828,000 square miles. (Before the title changed hands, the country itself was only 867,000 square miles.)

The land we bought from Napoleon was eventually carved into fifteen different states. Today, Louisiana is a paltry 43,000 square miles, while our next-door neighbors from the former Republic of Texas reign over 261,000 square miles.

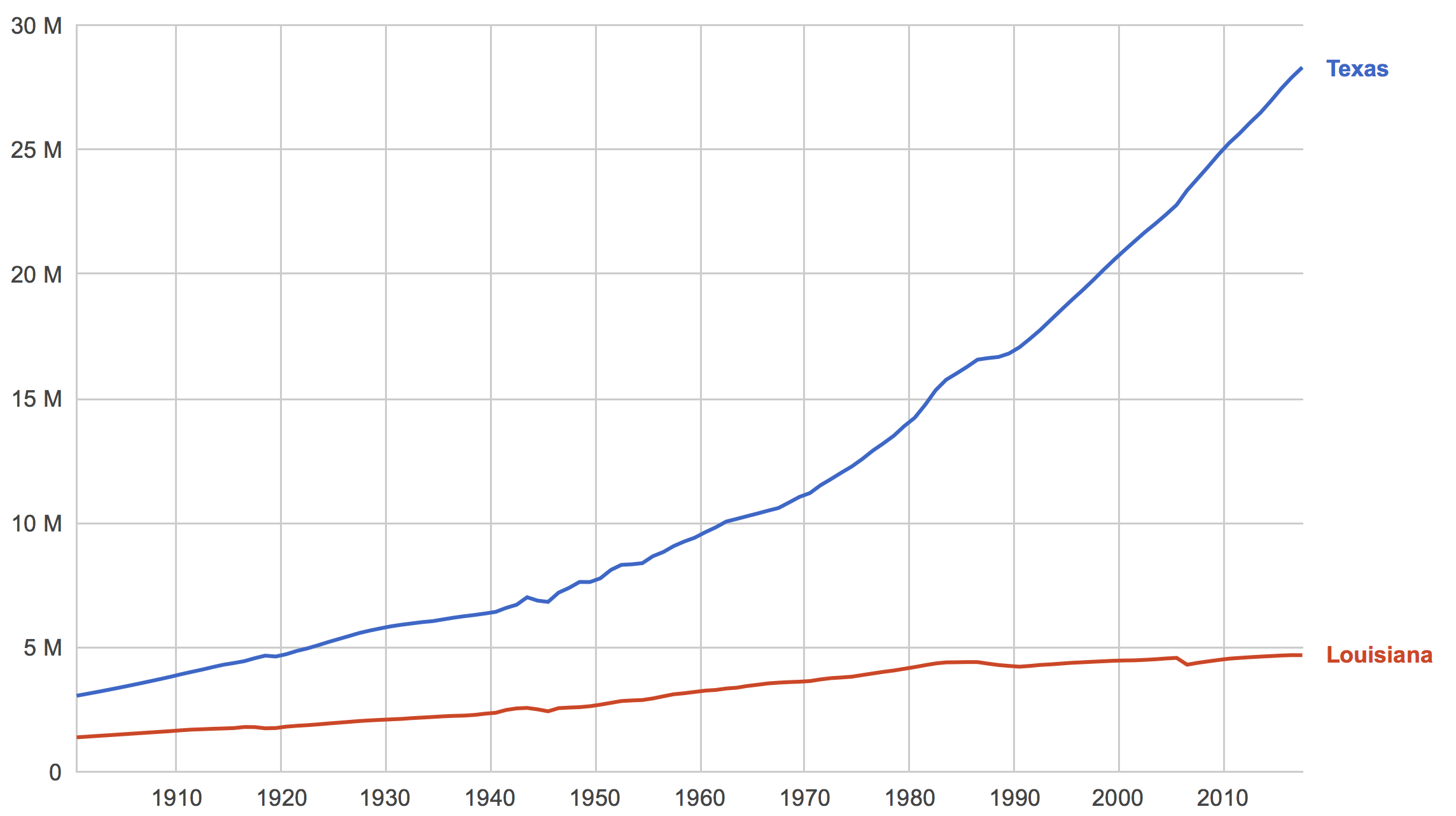

Texas, decades ago, competed with Louisiana, even though it was- in terms of land mass- more than five times the size.

From 1900 through 1940, New Orleans was listed as either the 12th or 15th most populated city in America, but there wasn’t a single city in Texas that made it into the top 20.

By 1960, however, Dallas was bigger than New Orleans, and Houston was the seventh most populated city in the country. Today, New Orleans would have to triple its population just to recapture 15th place, and six of the country’s twenty biggest cities are in the Lone Star State. Depending on who you ask, Houston is either the third or fourth most populated city in the nation.

For a moment, Shreveport bankers could have taken their chances on the wealth believed to be buried in their own backyard; instead, bankers from a mid-sized city on the Trinity River took those odds, and the fortunes they all made together ended up building modern-day Dallas. New Orleans could have been the national headquarters of the mega-trillion dollar energy industry, some have argued, but Houston asserted its intentions in the late 1950s and hasn’t been challenged ever since.

Today, only two Fortune 500 companies, Entergy and CenturyLink, are based in Louisiana. Dallas, on the other hand, is home to 22 Fortune 500 companies, the fourth-highest concentration in the nation; Houston is close behind, with 21 Fortune 500 companies headquartered there. Both cities, it’s worth noting, are led by Democrats.

Louisiana’s population has remained stagnant for more than a century, and its land mass is actually shrinking; every 48 minutes, the state loses a football field worth of land.

****

As an adult, I’ve inhabited these two distinct universes- Texas and Louisiana- for roughly the same amount of time, about a decade per state.

I spent my college years in Houston, occasionally barreling down the highway for a weekend in Austin. Whenever I drove back to my family’s home in Central Louisiana, I got to know some of the far-flung towns and cities of East Texas- Beaumont, Jasper, Livingston, and Woodville. In law school, I lived in Dallas, and during my years there, I watched the city transform itself into an international, cosmopolitan hub.

But I grew up in Alexandria, a place that liked to call itself “the heart of Louisiana.” Alexandria afforded me the unique vantage, from an early age, to learn about the entire state. From Alexandria, you can be almost anywhere in Louisiana within two or three hours.

Before John Bel Edwards won his campaign for governor in 2015, Democratic candidates had lost in fourteen consecutive statewide elections. The Democratic drought in Texas, though, has lasted even longer, more than 24 years.

But Democrats in Texas understand there are reasons to be optimistic. The state is home to more African Americans than anywhere else in the country, and demographers project that Latinos will outnumber whites within the next four years.

Nonetheless, political strategists in Texas are universally stunned by Beto’s breakthrough, though most are still skeptical of his chances of actually winning. Polls show Cruz enjoys a lead of- on average- around 3.3 points, and right now, elections guru Nate Silver pegs O’Rourke’s chances of winning at 30.6%. That doesn’t mean he’s a skeptic though.

“Beto O’Rourke really has a chance in Texas,” he reported.

Notably, Silver’s model includes what he calls a “fundamentals calculation,” which, surprisingly, advantages O’Rourke.

“I was pretty sure that once we introduced non-polling factors into the model — what we call the ‘fundamentals’ — they’d shift our forecast toward Cruz, just as they did for Marsha Blackburn, the Republican candidate in Tennessee,” Silver writes. “That’s not what happened, however. Instead, although Cruz is narrowly ahead in the polls right now, the fundamentals slightly helped O’Rourke. Our model thinks that Texas ‘should’ be a competitive race and believes the close polling there is no fluke.”

Win or lose, Rep. O’Rourke has permanently changed how campaigns should be run in the age of social media, and in so doing, he has reintroduced the fundamentals of retail politics, a style of electioneering that Louisiana had once mastered more fully than anywhere else.

Something big is happening in Texas.

I was there during its last major statewide election, advocating for Wendy Davis’ gubernatorial campaign. There was an unspoken acknowledgment, even among members of her own campaign, that Wendy wouldn’t win; their hope, though, was that it wouldn’t be a landslide.

It was. Davis lost in a landslide.

This is different. I repeat: Something big is happening in Texas.

About a year ago, I interviewed Jason Kander. He was fresh off his unsuccessful campaign for U.S. Senate in Missouri, and despite his loss, his name was the first mentioned by President Barack Obama in response to the question, “Who is the future of the Democratic Party?”

Kander may have lost, but he outperformed Hillary Clinton in his home state by nearly 16 points. And he ran as a pro-choice and much more progressive Democrat than the party’s standard-bearer.

“Honesty builds credibility,” Kander told me, even if that requires Democratic candidates in red states to tackle difficult questions about abortion or LGBT rights or gun control.

“Again,” he said several times, “be true to yourself.”

I have no idea if Beto O’Rourke ever heard Kander’s message, but their playbooks are awfully similar.

“In Louisiana, politics is theater,” Andrew Kolker observed in 1992, a year after Edwin Edwards defeated former klansman David Duke in the most consequential gubernatorial election in modern American history.

“Louisiana, if you look at it traditionally, has also been more progressive than all the other states surrounding it,” Louis Alvarez explained. Alvarez and Kolker were the filmmakers of the must-see PBS documentary “Louisiana Boys: Raised on Politics.”

26 years later, their film is still relevant, and their observations remain true, which is one of the reasons Democrats should pay attention to the enthusiasm a candidate for a statewide race in Texas has generated right here in Louisiana.

Two years after the release of “Louisiana Boys,” Democrats lost control of Congress for the first time in nearly a half of a century, and its leaders scrambled for a new strategy.

A group of predominately Southern Democratic congressmen conducted brainstorming sessions in the offices of Rep. Billy Tauzin of Louisiana’s Third District and Rep. Jimmy Hayes of Louisiana’s Seventh District, and together, they crafted the framework for a new caucus.

Democrats, they believed, had been defeated by running too far to the left, and the national party was out-of-touch with the political realities of the Deep South. To remain competitive, they concluded Southern Democrats would need to emphasize their conservative bona fides.

On the walls of their offices, both Tauzin and Hayes showcased paintings by the Louisiana artist George Rodrigue, who is best known for his iconic Blue Dog.

Their new caucus would be called the Blue Dogs, a nod to both Rodrigue’s famous dog- whose real name was Tiffany- and to the Yellow Dog Democrats of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

There is another version of the Blue Dog creation story. Some attribute the term to former Texas congressman Pete Geren, who had once complained that conservative Democrats were being “choked blue” by their more liberal colleagues.

Perhaps it’s not too surprising that Texas and Louisiana compete for credit for creating the Blue Dogs. In both states, Blue Dog Democrats dominated intra-party politics for nearly two decades, and during those two decades, both states became reliably red.

A year after co-founding the Blue Dogs, Billy Tauzin and Jimmy Hayes defected to the Republican Party. Pete Geren would go onto serve in the administration of George W. Bush.

The Democratic Party never abandoned these Southern elected officials, as they liked to claim. They abandoned the Democratic Party, and in doing so, they damaged the prospects of other, actual Democrats in their home states. To win as a Democrat in the American South, you’d need to be obsequiously pro-business, pro-gun, and pro-life. That was the only acceptable formula.

The irony, of course, is that this occurred during the administration of Bill Clinton, a former governor of a small Southern state who won Louisiana in his 1992 presidential campaign and then again in 1996.

Today, Blue Dogs are an endangered species, nearing extinction.

Conservatives, not surprisingly, began wondering why they should vote for a conservative Democrat instead of the real deal. To echo Jason Kander, Blue Dogs weren’t being true to themselves or to their political party. Voters noticed, and the Democratic Party in both Texas and Louisiana has struggled for relevance ever since.

Beto has already upended the conventional wisdom about what Democrats need to do in order to compete in a ruby-red state in the South, but his astonishing breakthrough isn’t exclusively attributable to his personal charisma. Beto has thrown out the Blue Dog blueprint, and while he has consistently reached out to Republicans and independents, he is also running as an unabashed liberal.

During his first debate with incumbent Ted Cruz, O’Rourke spoke passionately about racial inequities in the justice system and his support of Roe v. Wade. He argued in favor of granting citizenship to the nation’s 12 million Dreamers and in support of Medicare for All; he repudiated President Trump’s proposal for a border wall and spoke about the importance of investigating allegations the Trump campaign conspired with the Russian government in order to interfere with the integrity of the 2016 election.

Yes, he also declared his full support of the Second Amendment, but he emphasized the need for enhanced background checks and restrictions on owning “weapons made for the battlefield.” “Thoughts and prayers, Sen. Cruz, just aren’t going to cut it anymore,” he said.

You’re not supposed to be able to say things like that in a state like Texas, yet Beto is and his message is resonating.

There is another important reason for O’Rourke’s breakthrough, a point he made at least five times during his debate with Ted Cruz: During the past eighteen months, O’Rourke has visited all 254 counties in Texas. Cruz attempted to dismiss the significance of his opponent’s shoe leather campaign, suggesting that it amounts to nothing more than a series of photo ops for the press, but anyone who follows O’Rourke on social media knows that the candidate drives himself across the state.

The press may be paying attention now, but for the first year, it was just Beto and a couple of young campaign staffers on the road to the state’s far-flung corners and small towns that had long been taken for granted by their junior United States Senator. Ted Cruz may have visited all 99 counties in Iowa when he ran for president two years ago, but he still hasn’t visited every county in his own state.

People have a more difficult time caricaturizing a politician they’ve met in person or a candidate who has gone out of their way to visit their hometowns. When Ted Cruz suggested that O’Rourke was nothing more than a radical socialist, out of touch with the people of Texas, there were tens of thousands of rural, predominately conservative voters who knew better.

It remains to be seen whether anyone else will be as successful at using Facebook Live to document their campaign in real-time, though it’s a certainty others will try to replicate Beto’s social media strategy. More than 150,000 people watched O’Rourke hit up a Whataburger drive-through on the night of his first debate in Dallas; early the next morning, tens of thousands tuned in to watch him and the Castro twins, Julian and Joaquin, drive to a campaign rally in Del Rio, a border town of 40,000 people located a couple of hours away from San Antonio. The next day, as he drove to an event in Lubbock, even Mark Zuckerberg tuned in. No politician had ever before used his technology as effectively as a Democratic congressman from El Paso, Texas.

If politics is theater, then politicians need to know where the audience is. Today and for the foreseeable future, it’s largely online. But to successfully reach people online, candidates can’t present themselves as an actor reading from a script. You need to be “true to yourself.”

The country became familiar with Beto O’Rourke after a video of him speaking about NFL players protesting racial inequities in the justice system went viral, but for those who have paid closer attention to his campaign, his Facebook Live videos from the road are much more significant. As I’ve said before, O’Rourke is currently filming the best political documentary of my lifetime, and he’s broadcasting it in real-time, from his phone.

So, what does this mean for Texas’ neighbors in Louisiana? And what can Louisiana Democrats learn from Beto’s campaign?

First, Texas may be richer and bigger than Louisiana, but our political landscape is very similar. Texas has Ken Paxton, and Louisiana has Jeff Landry. Louisiana has John N. Kennedy and Clay Higgins, and Texas has Greg Abbott and Dan Patrick. In both states, the right-wing has become dramatically more partisan, while those on the establishment left have worked harder to attract Republicans than in cultivating their own base.

O’Rourke’s campaign should force Southern Democrats to rethink their assumptions and their messaging. In Louisiana, that means embracing our progressive traditions and reaching out to people on all corners of the state, not just the reliably liberal New Orleans. It means learning the state in the same way many of us from Central Louisiana know it and the way Beto now knows Texas.

When hundreds of people showed up in August to hear O’Rourke at a town hall in Navasota, Texas— a town of only 7,000 in between Houston and Austin— a friend from my hometown said he wasn’t surprised. “People like to forget that small towns in the South are still home to gay people and minorities, that small towns struggle with poverty much more than those in big cities,” he said. “These people have been ignored by most Democratic campaigns, but if Democrats pay more attention to rural voters, they will show up. And Democrats can change the narrative.”

The Yellow Dog is extinct. The Blue Dog is an endangered species.

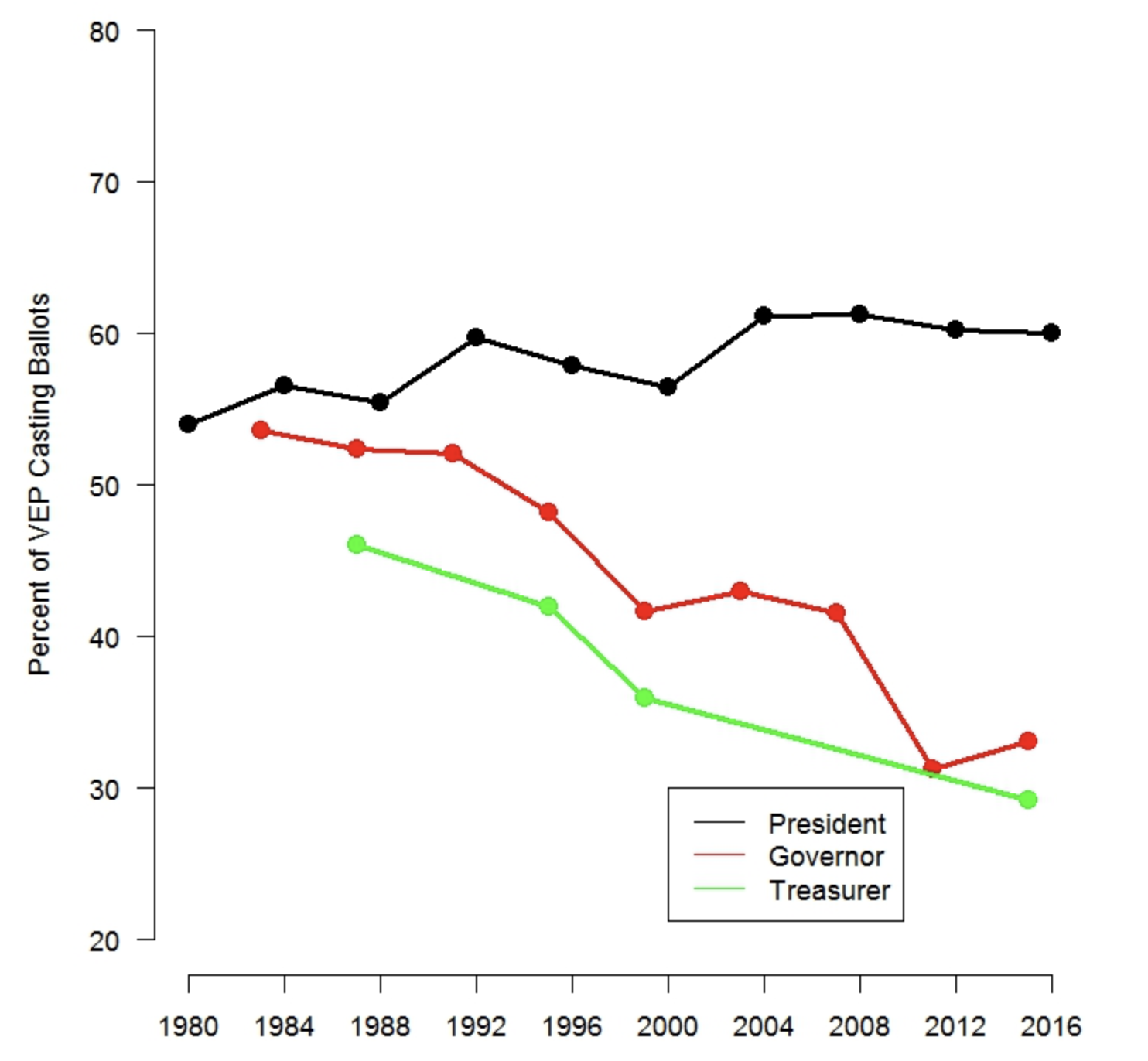

Yet Democratic voters never really went away; they were just taken for granted while their party’s candidates worried more about appealing to Republicans. Eventually, they stopped showing up. Louisiana now ranks as one of the worst states in the nation for voter turn-out. Texas is the worst.

As it turns out, when candidates decide to campaign in places long ignored, the people who live in those places decide to show up again. Just ask Beto O’Rourke.