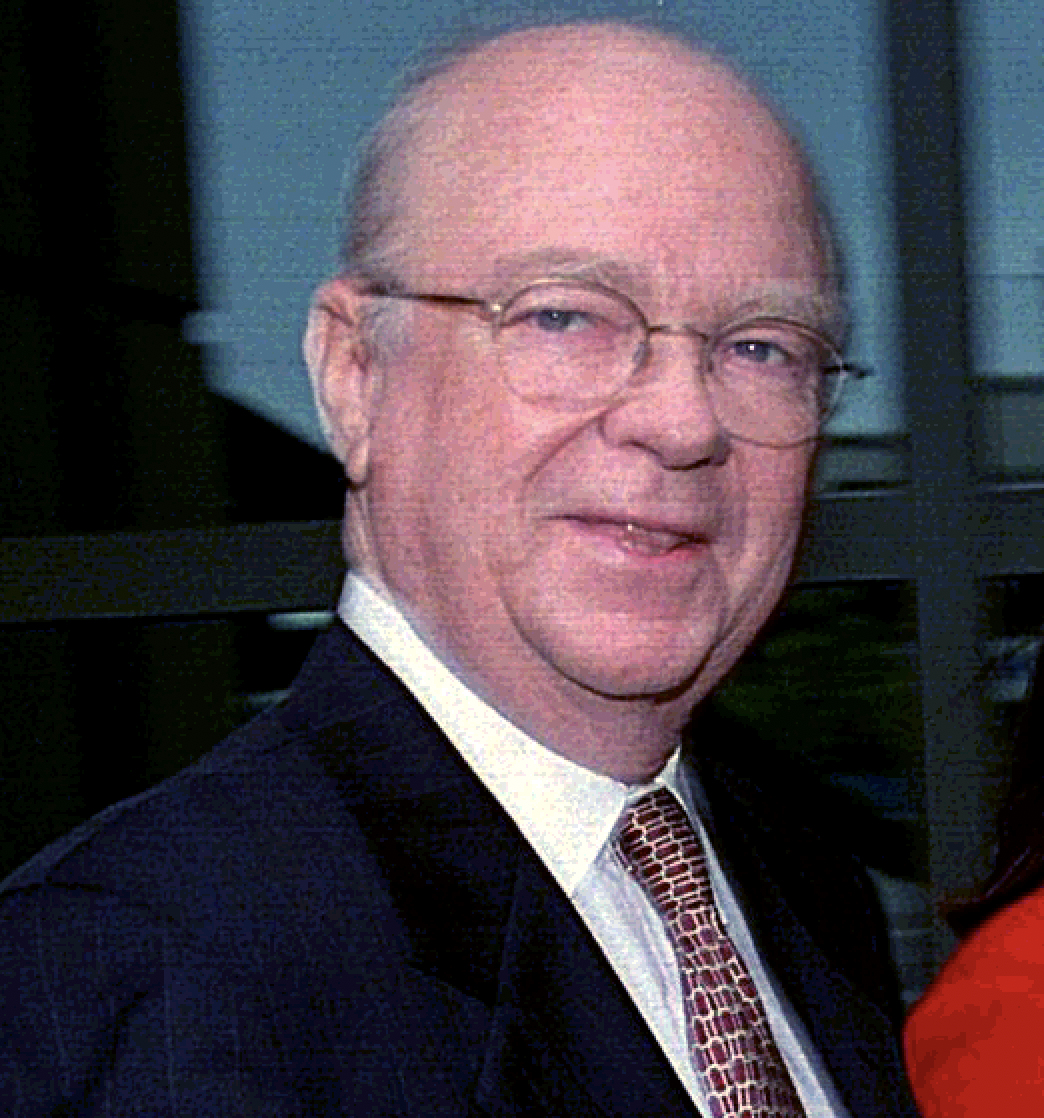

Political consultant Raymond Strother talks about campaign commercials in an interview on C-SPAN. Nov. 5, 1984.

In the run-up to the 1988 election, the Democratic nomination was Gary Hart’s to lose. He ran an excellent campaign as the runner-up to Walter Mondale in 1984; picking the previous cycle’s runner-up looked like a wise choice. It had worked for the GOP with 1976 runner-up Ronald Reagan as their 1980 nominee.

This time, though, things did not go as planned.

The Hart dreadnought sank in a sea of scandal in 1987. There had long been rumors that Hart had zipper issues and a troubled marriage. Hart’s close friendship with legendary Hollywood hound Warren Beatty helped fuel the gossip.

The world was different then: private lives were considered off-limits unless they affected a politician’s job performance, and even then, the old boys club kept each other’s secrets. That began to change with the pursuit of Gary Hart’s sex life.

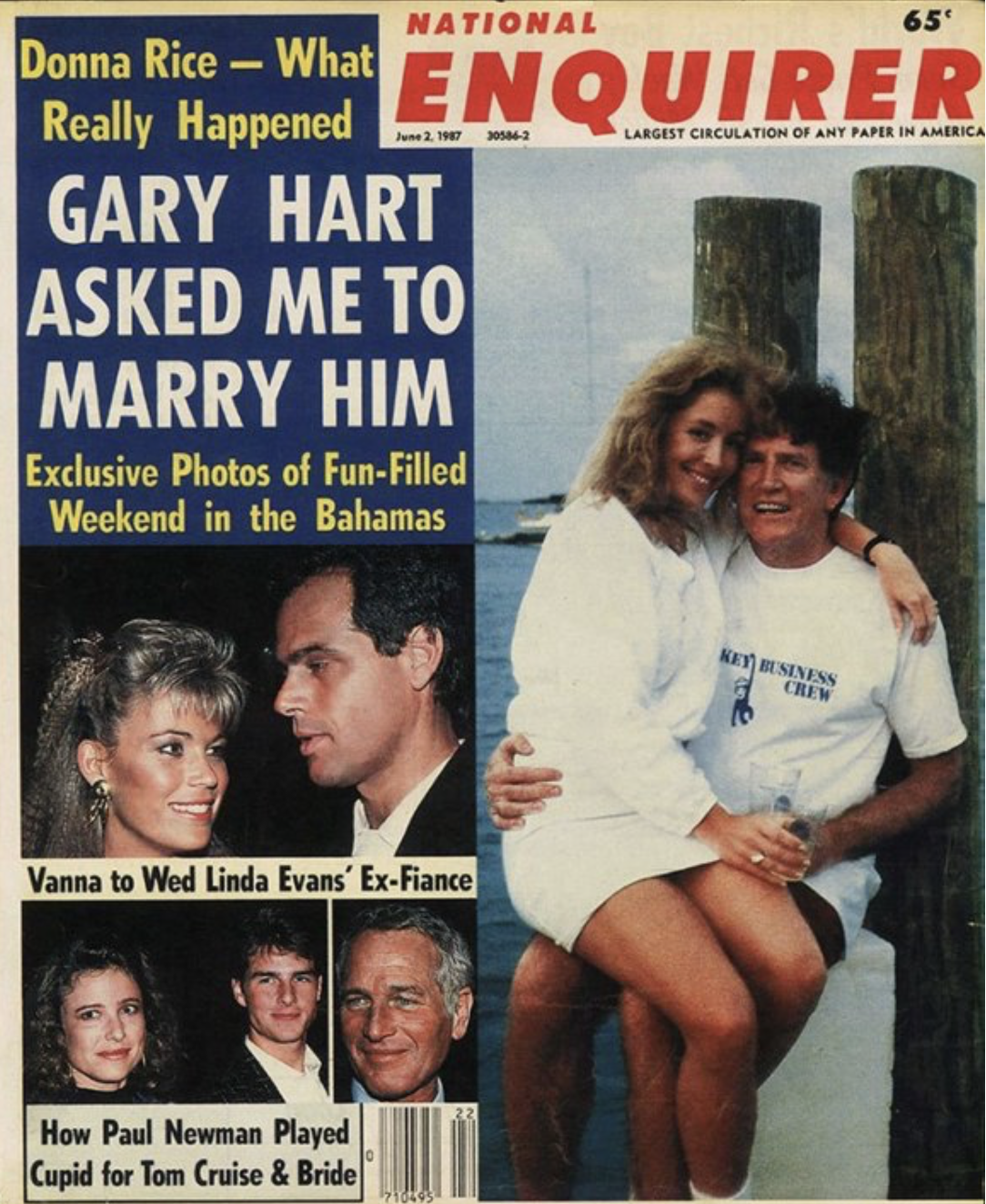

Hart’s chances to be president unraveled in the summer of 1987 with this National Enquirer cover story:

In case you’re wondering why I’m on about Gary Hart 31 years after his campaign imploded, the Atlantic‘s James Fallows has published a piece with a provocative title: “Was Gary Hart Set Up?“

Fallows recently had an extended conversation with Hart’s 1984 media advisor, Raymond Strother, about what happened that day.

Here’s where the Louisiana connection kicks in: Strother, an LSU graduate, made his bones in Louisiana politics working for the late Gus Weill. (James Carville worked for Strother for a time). Another Louisianian, Billy Broadhurst, was there when Gary Hart had his fateful meeting with Donna Rice.

Here’s the gist of Fallows’ piece: Ray Strother told him that infamous GOP hatchet man and one-time RNC Chairman, Lee Atwater, who along with Roger Ailes ran the 1988 Bush campaign, had confessed to Strother that he was behind the Hart set up:

But later, during what Atwater realized would be the final weeks of his life, Atwater phoned Strother to discuss one more detail of that campaign.

Atwater had the strength to talk for only five minutes. “It wasn’t a ‘conversation,’ ” Strother said when I spoke with him recently. “There weren’t any pleasantries. It was like he was working down a checklist, and he had something he had to tell me before he died.”

What he wanted to say, according to Strother, was that the episode that had triggered Hart’s withdrawal from the race, which became known as the Monkey Business affair, had been not bad luck but a trap.

But was the plotline of Hart’s self-destruction too perfect? Too convenient? Might the nascent Bush campaign, with Atwater as its manager, have been looking for a way to help a potentially strong opponent leave the field?

“I thought there was something fishy about the whole thing from the very beginning,” Strother recalled. “Lee told me that he had set up the whole Monkey Business deal. ‘I did it!’ he told me. ‘I fixed Hart.’ After he called me that time, I thought, My God! It’s true!”

I must admit that my bullshit detector went off when I read this piece. When he was dying of cancer, Lee Atwater directly apologized to several people he felt he’d harmed including 1988 Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis, who was the victim of the racist Willie Horton ad:

Friends said Mr. Atwater spent his final months searching for spiritual peace. The man renowned for the politics of attack turned to apologies, including one to Michael S. Dukakis, the Massachusetts Governor who was the 1988 Democratic Presidential nominee.

Mr. Dukakis was the target of a campaign advertisement about Willie Horton, a black convicted murderer who escaped from the Massachusetts prison system while on a weekend furlough and raped a white woman and stabbed her husband. The advertisement became a central focus of the 1988 campaign.

“In 1988, fighting Dukakis, I said that I ‘would strip the bark off the little bastard’ and ‘make Willie Horton his running mate,’ ” Mr. Atwater said in the Life article.

“I am sorry for both statements: the first for its naked cruelty, the second because it makes me sound racist, which I am not.”

Mr. Dukakis called the death a tragedy. “We obviously were on opposite sides of a tough and negative campaign, but at least he had the courage to apologize,” Mr. Dukakis said. “That says a lot for the man. My heart goes out to his family.”

If Atwater was “searching for spiritual peace,” why did he apologize to Strother and not Hart directly? The implication is that the apology came because they were both political handlers.

But Gary Hart got his start in national politics as George McGovern’s 1972 campaign manager. Their general election campaign was a mess, but their primary campaign was a masterpiece that has been emulated by Democratic insurgents ever since including Hart himself. If Atwater felt collegial with Strother, why not Hart? He was the real victim, after all.

Lee Atwater was a political slimeball who honed his craft working for right-wing Southern pols: dirty tricks and attack ads were his forte. He was quite capable of setting up a honey trap and springing it on Gary Hart, but the story implies that it was Louisiana lawyer and political fixer Billy Broadhurst who helped set him up.

Fallows mischaracterizes Broadhurst:

Hart knew that Strother had been friends with Billy Broadhurst, the man who had taken Hart on the fateful Monkey Business cruise. According to Strother and others involved with the Hart campaign, Broadhurst was from that familiar political category, the campaign groupie and aspiring insider. Broadhurst kept trying to ingratiate himself with Hart, and kept being rebuffed. He was also a high-living, high-spending fixer and lobbyist with frequent money problems.

Broadhurst may have been an arriviste in national politics, BUT he was a heavy-hitter in the Gret Stet of Louisiana. Far from being a “campaign groupie,” Broadhurst was one of four-term Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards’ closest associates as well as an informal and influential adviser to many other Louisiana politicians. Broadhurst was a fixer in the finest sense of the term as this passage from a 1987 Vanity Fair article by Gail Sheehy illustrates:

But let us not forget that the man who chartered the party boat for Hart was William Broadhurst, a friend and political intimate. Billed as “Mr. Fix It” for Edwin Edwards, the notorious Louisiana governor who beat a corruption charge, Broadhurst seems to specialize in getting close to politicians who are out of control. (The article was written 14 years before Edwards was convicted of racketeering.)

“Billy B.” arranged planes for the governor’s gambling trips and enjoyed his jokes about Edwards’s well-publicized womanizing. In the midst of the Hart—Monkey Business flap, a state senator asked the governor what he thought of his boy Broadhurst. A vintage Edwards comment came back: “Oh, Billy B., he was more careful when he was pimping for me.”

Another thing that bothers me is the notion that Hart kept rebuffing Broadhurst. If so, why did Hart accept his invitation to Bimini? Why did he refer to him as Mr. Deep Pockets? Here’s how a 1987 Washington Post article described their relationship:

It was around this time that fellow Louisianan and political consultant Raymond Strother introduced Broadhurst to Hart. The two hit it off instantly. Broadhurst became an active Hart fundraiser, bringing in about $40,000 at three events.

Soon, Broadhurst was flying around the country with Hart on various campaign swings. Last year, the Harts were the Broadhursts’ guests at the Super Bowl.

“Gary Hart was very smart,” says Bode. (Ken Bode was an NBC political correspondent and Broadhurst friend.) “They liked each other — and Broadhurst was key to the Edwards financial network. He was Gary Hart’s hole card for Louisiana.”

Broadhurst hoped for a high appointment in the never-to-be Hart administration perhaps even Attorney General. Why would he blow up his dreams by helping to set up Hart? It makes no sense.

It’s an open secret in Louisiana political circles that Strother remained pissed at Broadhurst over the Hart mess. One theory of the Strother revelation is that he wanted vengeance on Broadhurst for what might be called the Bimini bummer. But Broadhurst died in 2017, so why the revelation? Why now?

None of this makes any sense.

Raymond Strother turned 78 on October 18th. I’m not a mind reader. I’m having a hard time understanding his motivation for floating this unverified and unverifiable story now. He’s apparently been gravely ill. He believes that the nation suffered a major blow when Hart’s chances for the presidency sank like an unmoored yacht in a hurricane. One possible motive is guilt over having introduced Billy Broadhurst to Gary Hart, which led to the crazy chain of events that ended Hart’s political career.

As to the Atlantic article, James Fallows (a writer and editor I admire) is guilty of having accepted Strother’s word at face value. I don’t expect Fallows to be an expert in the arcana of Gret Stet politics. But he could have consulted with Mr. Google to learn that Broadhurst was no mere “political groupie” but so wired in to Louisiana politics that Hart considered him his “Louisiana hole card.”

Ray Strother’s motivation remains a mystery to me: my Ouija board and crystal ball came up empty. It’s a great pity that this interesting and accomplished man will be best remembered for this incident. His memoir Falling Up: How A Redneck Helped Invent Political Consulting is one of the best books about politics I’ve ever read. He’s a great storyteller and a witty and lucid writer. Here’s how he described the Hart-Broadhurst relationship therein:

The relationship between Hart and Broadhurst flourished. I don’t think the controlled, rigid Hart had ever met a man with Billy Broadhurst’s bayou joie vivre. He made Hart laugh, and nothing Hart could do would be beyond the Louisiana moral boundaries that Billy considered normal. Not that I blame Bill for Hart’s downfall. I don’t, any more than I blame myself. I still consider the whole thing just bad luck and maybe even political mischief.

Lee Atwater died in 1991.

Ray Strother’s memoirs were published by LSU Press in 2003.

If the “Atwater confessed to me” story were true, that would have been the perfect time to tell the truth about the Bimini bummer. It would have sold books and been the topic of conversation just as it is today.

Once again, we’re confronted with the central mystery: why now?

Here’s my hunch: Strother seems to have romanticized and sanitized his memories of Gary Hart. Why? The Current Occupant of the White House is a vulgar, venal idiot whereas Hart is a brilliant man who made a stupid mistake and paid for it dearly.

It was the nation’s loss too: If Hart had beaten Poppy Bush, his son’s reign of error may have never occurred. It’s one of American history’s more tantalizing what ifs.

In the end, I believe Raymond Strother in 2003, not 2018.