It took us both a couple of days to process and organize our commentary on what national sports reporters have characterized as the worst missed call in NFL history. That, of course, will always be an opinion, but it is impossible to deny the consequences of the officiating crew’s negligence and the unforgivably incompetent leadership of NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell.

Super Bowl 53 in Atlanta this year will not have a legitimate winner, which is unfortunate for the City of Atlanta (which invested an absurdly wasteful amount of money), both of the teams, their players, their coaches, and their fans. The NFL, in its infinite wisdom, designed the logo like they usually do, with Roman numerals, which is befitting. 53 in Roman numerals is LIII, but because they added the Lombardi Trophy in the middle, it incorrectly appears as LIIII. Either way, phonetically, the next Super Bowl is pronounced “lie.”

- I. The Dream.

- II. The NFL’s Worst Nightmare.

- III. The Most Exclusive Club in America.

- IV. Don’t Wait on Goodell.

I. The Dream.

During the past three weeks, the City of New Orleans has hosted a series of community events, lectures, and volunteer drives, all in preparation for yesterday. Last morning, New Orleans hosted a parade in honor of a man who meant so much to the people of New Orleans that we built two statues in his honor. 61 years ago, inside of the New Zion Baptist Church in a neighborhood known as Central City, he joined nearly 100 people from across the country to launch a new organization: the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Its members elected him as their first president.

He was a young preacher from Atlanta named Martin Luther King, Jr.

He befriended one of New Orleans’s most influential gospel singers, Mahalia Jackson, and six years later, she read drafts of the speech he was preparing on behalf of the SCLC for the March on Washington.

With the cameras rolling, in front of the largest audience he had ever addressed, under the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial, Jackson yelled out, “Tell ’em about the dream, Martin! Tell ’em about the dream!”

And as if struck by a bolt of lightning, King delivered some of the most memorable and consequential speeches in history. The lines that are etched into our collective memory and in monuments across the country weren’t actually in his prepared remarks; Dr. King was riffing off of a sermon he had recently given, and perhaps Mahalia Jackson understood its jazz– its cadence and its profundity– in a way he didn’t entirely appreciate.

There was a football game on Sunday in New Orleans, and with under two minutes to play, analysts at CBS Sportsline pegged the New Orleans Saints with a 98% chance of winning. The team was almost guaranteed a trip to the Super Bowl.

By now, even if you don’t follow football, you know what happened next.

Fans of the Falcons, the Saints’s long-time divisional rival, gloated online. Saints fans have been taunting them for blowing a 28-3 lead against the New England Patriots midway through the third quarter two years ago in the Super Bowl. Not all football fans are created equal, and there were more than a handful of people from Atlanta who took the shocking loss hard. Others were more sensible; it’s just a game, after all.

When asked which teams she hoped to play in the Super Bowl, Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms said, “Anybody other than the Saints. Just anybody other than the Saints. I know there’s going to be a bounty on my head for saying that.” She subsequently walked back her comments, which were clearly intended to be funny but also beneath the dignity of her office.

At least one national sports commentator, who cares for neither team, had expressed public concern over the prospect of a Saints Super Bowl win in Atlanta, worried it would increase the number of fights and assaults.

“I’m sorry she feels that way. We would welcome them here. At the end of the day they shouldn’t be mad at us that they suck.”

New Orleans City Councilman Jay Banks

No doubt, there were Saints fans who should have been less cruel to their friends from Atlanta, but the Falcons collapse was not caused by horrific officiating. The consensus is nearly universal, and once hardcore Falcons fans get over the schadenfreude, they will be able to acknowledge: What happened in New Orleans on Sunday is incredibly damaging to a league and, particularly, to a commissioner whose credibility is already in free-fall.

There is such a thing as a healthy or good-natured rivalry; it’s a part of the myth-making that all professional sports leagues rely upon, recurring dramas that construct the narrative to sell more tickets, merchandise, and sponsorships. At its best, it also can build a sense of community.

But at its worst, it alienates and isolates like-minded people in politically and economically marginalized communities from maximizing their collective potential. It’s a real phenomenon. New Orleans and Atlanta are both majority-minority cities in the Deep South; they’re both enclaves of progressive politics surrounded by conservative suburbs, and the NFL, in particular, plays a prominent role in each city’s culture.

More than a few Falcons fans gloated: New Orleanians will be miserable over this for a long time. They’re right. Sort of.

Because yesterday, New Orleanians began planning a parade for their football team and actually held a parade for a preacher from Atlanta.

It’s hard not to wonder what Dr. King would have made of the corporate religion of American professional football and, according to multiple peer-reviewed studies, the ways in which social media has exacerbated and encouraged hostilities between friends and family members who root for opposing sports teams.

Meanwhile, Jerry Jones’ team, the Dallas Cowboys, which has not won a Super Bowl in 23 years, received more than $320 million from the government and is now the most valuable sports franchise in the world, worth a staggering $4.8 billion. They play in a tax-payer subsidized shrine to its owner, a stadium that is nearly thirty miles away from Dallas, and the whole game-day experience can easily cost a family of five $1,000 for mediocre seats and a parking nightmare.

They still call themselves “America’s Team,” which is not only because they’ve out-priced their local, working class fanbase, but because Jerry Jones is the only owner who controls his team’s merchandising. Sure, they’d like to win, but it’s ultimately unnecessary. In 2017, they took in more than $840 million and made more than $350 million in profit. They didn’t make the playoffs, as if it mattered.

II. The NFL’s Worst Nightmare.

“Monday morning quarterbacking”– a euphemism for those who specialize in second-guessing every decision made during the course of an entire game– is usually a pointless exercise in understanding the meaning of causality, the Butterfly Effect applied to football.

Sure, the Saints could have sealed up the NFC Championship game against the Rams a lot sooner than they did, with some better play-calling down the stretch, a defensive stop somewhere along the line, and Drew Brees in particular not making some inexplicably bad throws. (The final interception stands out the most, but the Saints might have ran the clock out on the Rams if he hadn’t thrown a slant to Michael Thomas low, and he badly missed an open Ted Ginn downfield on a third down pass earlier in the fourth quarter.)

Of course, all of those mistakes pale in comparison to a referee call– or lack thereof– that kept the Saints from sealing the game away and gave the Rams another chance:

Here, Rams cornerback Nickell Robey-Coleman blatantly commits pass interference on Tommylee Lewis– and, to boot, hits him with a helmet-to-helmet hit that should also draw a flag. The referees, of course, call nothing.

The Saints should have the ball on first and goal with 1:41 left and the Rams with only one timeout. If the Saints even just took a knee for three straight plays, they could kick a short field goal and leave the Rams with 5-10 seconds left on the clock. Instead, they have to kick the field goal now, and the Rams get the ball back with enough time left to drive to tie the game with a field goal, then winning in overtime with a preposterous kick on a 57-yard attempt by Greg Zeuerlein, one that might have been good from ten yards further out.

The Saints could have done a lot differently throughout the game and down the stretch, but all that will pale in the discussion about this game, and the historical record thereof, to the no-call on Robey-Coleman’s pass interference. It wasn’t even the first no-call on a helmet-to-helmet hit of the game:

After the above play, the referees determined that Hill was staggered enough that he needed to be taken off the field for concussion evaluation– but apparently the helmet-to-helmet hit that caused that wasn’t worthy of a penalty.

Nickell Robey-Coleman himself admitted the penalty should have been called. The NFL admitted it to Sean Payton immediately after the game.

Ultimately, Roger Goodell was satisfied with the result. Remember, the primary objective of the 2018 season was to bring football back to Los Angeles, the country’s second-largest market. Serendipitously, the Rams were able to make it all the way to the Super Bowl, and as an added bonus, his referees stuck it to the team he’s had it in for almost ever since he got unilateral disciplinary powers.

Make no mistake: Despite the beneficence of Tom Benson to the league, Roger Goodell, no matter what he says in public, hates the New Orleans Saints, the minor market franchise in an impoverished and vulnerable part of the country.

Years ago, after the Saints win the Super Bowl, Goodell needed a high-profile scapegoat in a small market to demonstrate to the American public he was finally interested in taking medical research on chronic traumatic encephalopathy seriously.

The media called it Bountygate, and it was a farce from the beginning (more later in the report).

Since then, every single offseason, Goodell has found himself embroiled in another controversy: He really cares about player safety, until he doesn’t; he really cares about domestic violence, until he doesn’t; he’s even willing to dismiss the laws of physics if it means sticking it to a player he thinks is getting out of line. (Indeed, given some of the suspensions handed out, it seems like Goodell’s decisions are in great measure retributive: Those who admit guilt and throw themselves at his mercy receive lesser punishments than those who maintain their innocence and fight to clear their name, even when the former commit significantly worse crimes.)

The NFL made a big deal about improving their officiating this year, even hiring full-time officials for the first time. Somehow this has resulted in even worse and more inconsistent officiating.

The NFL also made a big deal about player safety this year, even to the point of calling a number of specious roughing-the-passer penalties early in the season (mostly on Green Bay’s Clay Matthews). Yet somehow the referees missed two helmet-to-helmet hits against the Saints.

What else do you say about this? What do you say to all the fans whose tax dollars go toward team and stadium incentives, that the league can’t even deliver the fair and honest competition it promises in return? John Oliver has perhaps the best snd most disturbing commentary on the subject.

The New England Patriots won the AFC Championship Game in overtime.

If the referees call the NFC Championship Game correctly, we would get, at last, a matchup of the two longest-lived dynasties in the NFL today. Bill Belichick and Tom Brady are the only QB-coach combo in the NFL with a longer tenure than Sean Payton and Drew Brees. With the firing of Mike McCarthy and the resignation of Marvin Lewis, Belichick and Payton are the two longest-tenured head coaches.

Brady and Brees are the oldest starting QBs in the NFL, the only two in the league over 40 (as of last Tuesday, when Brees turned 40). The Patriots and Saints have never met in the Super Bowl. A dynastic matchup between those two franchises, in what could possibly be the last time around for both quarterbacks, would have been a fine summit for this NFL season, a fine way to put a capstone on the era of the last generation of QBs, before players like Patrick Mahomes and Jared Goff take up the mantle for the new generation.

It’s a shame we won’t get that now. It’s a shame we won’t get that directly due to bad officiating and negligent leadership.

III. The Most Exclusive Club in America.

There are 32 owners or representatives who gather a few times to discuss the business of the National Football League. It is the most exclusive club in the nation, and today, there are essentially only three ways to join: You either need to be billionaire waiting for another billionaire to die, an heir to a current owner, or the spouse of an owner.

Roger Goodell is the Commissioner of the National Football League, but he’s really just a consigliere for a couple of dozen billionaires and families with multi-generational wealth– namely, 31 of the 32 owners or ownership groups of a National Football League franchise: The granddaughter of the Firestone Tire fortune who married the grandson of Henry Ford, the brothers Mr. Johnson and Mr. Johnson, the husband of a Walmart heiress, a handful of self-made billionaires, and a roster of spoiled, overgrown children. Oh, and the nonprofit shareholders of the Green Bay Packers, an ownership model that they will never allow again.

21 of the NFL’s stadiums were built with taxpayer subsidized money, which has made those franchise owners even wealthier.

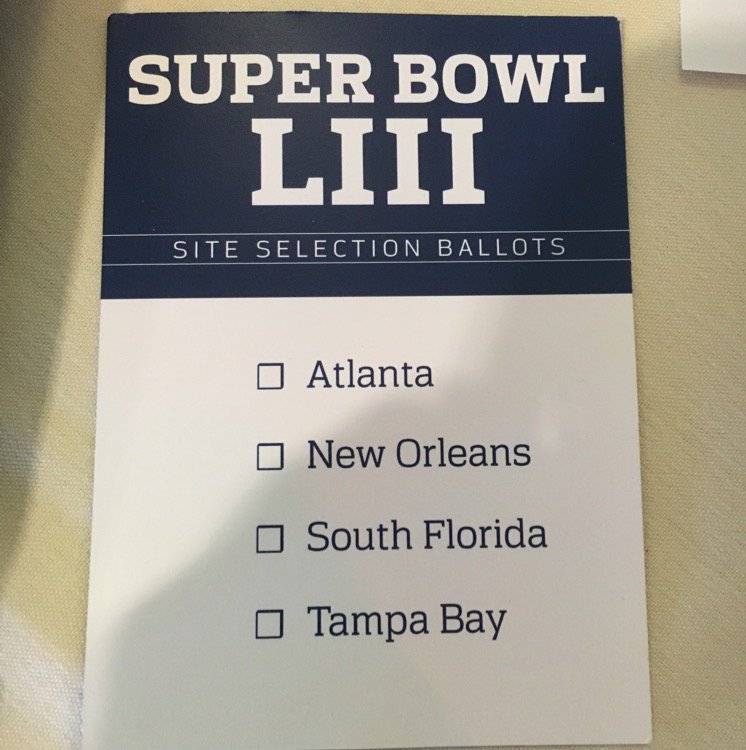

In May of 2016, the ownership club met in Charlotte, North Carolina at the luxury Ballantyne Hotel to vote which cities would win the opportunity to host the 2019, 2020, and 2022 Super Bowls.

According to contemporaneous reports, New Orleans was expected to win their bid for 2019, because they had narrowly lost out on hosting in 2018 and because they could not also compete for 2020 or 2021 due to conflicting events. 2019 would be their only shot.

The Big Easy easily made it into the top four.

Then, it made it into the finals against Atlanta. They were promising to spend a ton of public money and would be in a brand-new stadium.

Atlanta announced their win with a video featuring an inordinate amount of concrete and traffic.

They quickly decided the locations of the next two years: 2020 in Miami and 2021 in Los Angeles. Goodell was pushing for L.A. so enthusiastically that it didn’t matter there wasn’t a team or a stadium yet.

Eventually, they had to move the date back to 2022 because of construction delays, Tampa gets the Super Bowl in 2021 instead.

Roget Goodell says his job is to “protect the shield,” which is a reference to the league’s logo, but behind the shield aren’t fans or players or employees. The shield protects the wealthy owners who pay him $35 million a year to manage their family fortunes and leverage as much as he possibly can for them through the perfectly legal extortion of state and local governments.

“My job is to protect the integrity of the NFL and to make sure the game is as safe as possible,” he claimed in 2010, presumably with a straight face.

Steve Gleason’s punt block thirteen years ago isn’t remembered because the Saints were playing our main division rivals; it was a small symbol of the city’s redemption and worth.

IV. Don’t Wait on Goodell.

The NFL’s logo for this year’s Super Bowl, appropriately, is phonetically pronounced “lie,” spelled in Roman numerals. The Lombardi trophy’s placement makes it appear as Super Bowl 54, which is correctly spelled as LIV.

Notwithstanding the enormous amount of money you need to own any sports franchise– particularly a football team– there is a reason the wealthy hold on to their teams as long as they can, sometimes through multiple generations: It’s a legitimately fun job, one that allows you to travel across the country, insulates you from employee criticism (thanks to the overly broad “personal conduct” clause in the Collective Bargaining Agreement), and generates enormous profits. It’s virtually impossible to lose money as the owner of an NFL team, no matter how bad the product on the field or the news off the field is.

When Saints won the Super Bowl for the first time in 2010, there were no legendary curses that had finally been broken; the whole region had always seemed cursed. But the victory was cathartic and unifying– at least for a few days– for a region bitterly divided by politics, haunted by the original sins of slavery. The poorest, most exploited, most polluted, most incarcerated, and least educated region could win the biggest prize in American sports.

After the Saints won, an entire region– and particularly the city of New Orleans– went outside and embraced one another; grown men cried– out of joy and gratitude, yes, but also out of sadness for their fathers and friends who had passed away and who never believed something like this could ever happen, in the same way fans of the Boston Red Sox lit up cemeteries with their flashlights on the night the team finally broke the Curse of the Great Bambino.

Less than three months after the Saints won, a rig in the Gulf of Mexico exploded and killed eleven people. Oil spilled and spilled and spilled for five months, the largest man-made environmental disaster in American history.

And then a wealthy white man, the son of a right-wing U.S. Senator, tried his best to invalidate the one unifying and uplifting thing that we had celebrated as a region: The legitimacy of the Saints Super Bowl win.

On Sunday, ignoring a rule that provided him with the requisite authority, ignoring the assessments of his own executive-level officiating staff, and ignoring the open confession of Robey-Coleman of the Rams, Roger Goodell made this year’s Super Bowl illegitimate. He had the time, technology, and authority to correct the mistake; it is precisely why such a rule exists.

In 2013, sports reporter Reid Gilbert published Of Bread & Circuses, an exhaustively researched book that convincingly and thoroughly debunked the manufactured scandal of Bountygate. “As the events of Bountygate unfolded, Roger Goodell exhibited a consistent disregard for accuracy and, in some cases, the truth,” Gilbert writes. “As we learned, one of the defining patterns of Bountygate was that of unsubstantiated claims followed by eventual disapprovals.”

There is a mountain of evidence, much of which is unknown even to the fiercest Saints fans, that Roger Goodell was motivated by a personal animus against Sean Payton. Goodell’s predecessor, Paul Tagliabue, was called into arbitrate, and he cleared every single player who was punished by Goodell.

We understand the media’s impulse to praise Gayle Benson for issuing a strongly-worded letter essentially demanding a rule change. But that is not satisfactory. If she can, she should sue for breach of breach of contract, loss of economic opportunity, and demand Goodell finally be held accountability for his negligence and hypocrisy.

If this had occurred to Jerry Jones or Robert Kraft, a lawsuit would’ve been filed.