In 1957, in an essay titled “Reflections on the Guillotine,” French philosopher Albert Camus (1913-1960) wrote, “What then is capital punishment but the most premeditated of murders?”

He was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature that year.

Last week, May 6, the full Louisiana Senate debated capital punishment, in the form of SB 112. The proposed constitutional amendment authored by Sen. Dan Claitor (R-Baton Rouge) would have – if approved by voters in the fall – abolished the death penalty for any offense committed after January 1, 2021.

Last week, just one-third (rather than the required two-thirds) of Senate members said yes to that idea, and the bill was shelved.

This Tuesday, a House committee got the chance to advance an alternate version, HB 215.

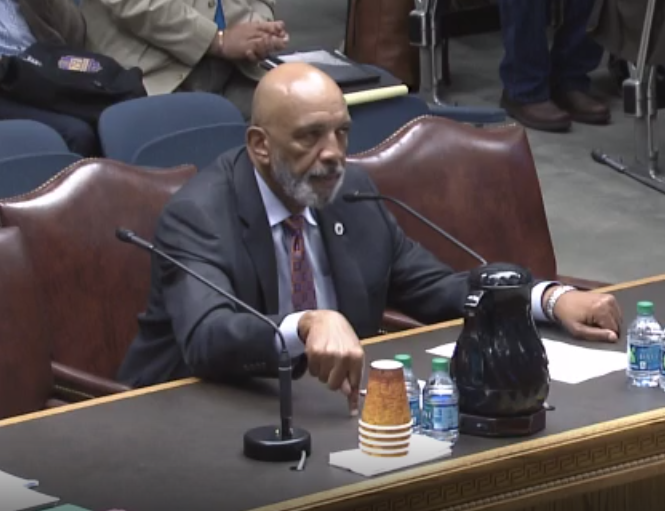

“This is a very, very important and emotional bill,” Rep. Terry Landry (D-New Iberia) told the Criminal Justice Committee. “This is prospective legislation, abolishing the death penalty from August 1, this year, forward. You’re going to hear testimony about past crimes and past convictions, but this is not about retrying anyone on death row, or about anyone who has already been convicted. This is about eliminating the death penalty as part of convictions going forward.”

The former commander of Louisiana State Police spoke gently. “I come from a law enforcement background. I’ve seen the carnage, the heinous crimes, but I’ve come to this point about the death penalty because I’ve grown spiritually as a man. I just fundamentally believe that taking a person’s life is essentially wrong.”

Taking a deep breath, Landry – who is making his third try to remove capital punishment from Louisiana’s laws in as many years – then said, “This is worthy of a full debate, by the full House. So I’m asking to move this instrument forward for that purpose.”

Practical, rational, unemotional testimony supporting Landry’s legislation followed, including pointing to the bill’s fiscal note, which says state costs will drop by $1.16 million in the first year of implementation, and decrease by as much as $3.75-million by the third year. Noting that the state’s cost to try, convict, house, and deal with the appeals of those sentenced to death is much higher than for other crimes, there was testimony that each death row inmate at Angola costs the state $64,000 per year, as opposed to the average healthy inmate costing the state just $13,800 annually.

Additionally, since 1977, eleven death row inmates have been exonerated.

“The only acceptable rate of execution of innocent people is zero,” stated Loyola-New Orleans professor Dr. Nicholls Mitchell. “Capital punishment is an antiquated, flawed, racist practice that needs to be abolished.”

Family members of murder victims spoke in opposition to the bill, giving voice to the anger they still feel toward the perpetrators of these untimely deaths. But their ire paled in comparison to the venom voiced by Michelle Perkins, who started a (private) Facebook group called “Stand Up For Louisiana Victims.”

“I’m from Livingston Parish, and I live in Caddo Parish now. I am married to a law enforcement officer who just marked 28 years on the force. I am insulted that Terry Landry has brought this bill and,” she said, throwing her hands in the air in a gesture of exasperation, “keeps braggin’ that he was law enforcement.”

Then, wagging her finger admonishingly at the 6-foot-5 chairman of the House Transportation committee, she continued: “I resent that y’all keep saying he is law enforcement. Well, let me tell you, I’m a law enforcement wife, and I can assure you that law enforcement families across the state of Louisiana does (sic) not feel the way that Mr. Landry does. We don’t want to abolish the death penalty. Cops are getting killed. They got targets on their backs. Our cities are wrapped in crime scene tape!”

Perkins was thoroughly worked up at this point, shouting and gesturing wildly, and Criminal Justice committee chairman Sherman Mack attempted to get her to tone it down.

“Hold up, hold up Ms Perkins,” Mack said. “We appreciate your passion. Trust me, I’m on your side, but let’s…”

“I’m sick of y’all pushin’ this, and I’m tired of y’all attacking these police officers constantly!” she continued, ignoring the chairman’s interruption. “All these special interest groups better pack their bags, and quit pushin’ this in Louisiana!”

“Ms. Perkins, you can’t threaten…” Mack said, making a half-hearted attempt to quell her raging.

“I am a Christian! I don’t know what Bible they’re readin’, but that’s not what my Bible says. If you kill somebody in the state of Louisiana, they need to be held accountable! I resent all this talk of ‘racism, racism racism,’ then y’all talkin’ about how much it’s gonna cost. That’s an insult to every law enforcement officer in the state of Louisiana!”

“Ms. Perkins…”

“That’s it! I’ve had it!” she shouted, and then revealed what truly had her undies in a bunch. “I’m upset. I was on vacation in Florida, and had to come back because this bill was being presented, and I’m fuming mad that I had to end my vacation to come back here. But this is my state of Louisiana. This is my home, and we are not gonna keep people alive that kill other people.”

“Ms. Perkins, thank you for comin’ to the Capitol,” Mack said, politely but firmly, indicating that her time at the table was done.

Some committee members were deeply offended by the woman’s words and tone, and made their disapproval known to their chairman and the public as a whole.

“To the victim families, I have sat where you are sitting,” Rep. Denise Marcelle (D-Baton Rouge) said. “I had a brother murdered, and I understand your pain. People have different perceptions of pain, so we shouldn’t badger victim families.” Turning to glare at Chairman Mack, she continued, “Neither should we call out the members of this body for their differences of opinion. Because when we’re talking about a margin of error for the death penalty, if one person dies that is wrongfully convicted, that one is too many. I support abolishment of the death penalty.”

“Killing a person won’t bring your loved ones back,” observed Rep. John Bagneris (D-New Orleans). “We need to look further than killing someone to get revenge.”

In his closing on the bill, Rep. Landry thanked those committee members who came to his defense, saying, “This is part of the process, and I don’t take anything said personally. I was law enforcement, a Vietnam vet, Louisiana State Police commander. I feel for the families, and I don’t take offense at them taking it out on the author of this bill. I am at peace, and I seek peace.

“This is not for political reasons. I am not seeking re-election or election to anything else. I’ve brought this bill three years in a row because I believe in it. Death by violence, death by government is wrong.”

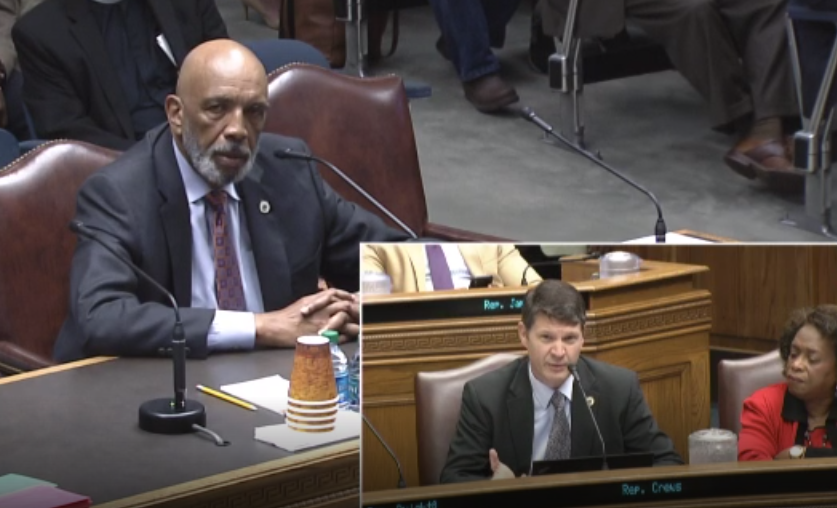

And while it is customary not to permit any other speakers once the bill’s author has made his closing argument, the chairman let Rep. Raymond Crews (R-Bossier City) respond directly to Landry.

“You argue death by government hands is wrong? I’d argue that it’s the only way it’s right!” the clearly agitated Crews argued. “We have to show how important life is by having a supreme penalty for taking a life. Life is so valuable that you can’t take it willy-nilly. The death penalty teaches morality.”

Pause for a moment, and compare Crews’ statement to this question posed by author Robert Heinlein, in his 1966 novel, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress: “Under what circumstances is it moral for a group to do that which is not moral for a member of that group to do alone?”

“I believe this is an important enough issue that each of us should vote,” the committee chairman stated. “ So while Rep. Marcelle has moved we report the bill favorably, with respect, I object, so we will take a roll call vote.”

Two Republican members were not in their chairs and did not vote, but the other seven Republicans on the 17-member committee voted no. The rest of the committee, seven Democrats and one Independent, voted yes.

The full House will likely debate the measure early next week, leaving barely enough time – if it passes – for the measure to move through the Senate side before the end of session June 6.