A pair of stilt walkers charged the City of Alexandria $5,000 to amble around its downtown for 40 hours over the course of three days last May. They were accompanied by a couple of “non-clown balloon artists,” who billed the same rate, $125 an hour, for a combined 36 hours. The quartet were all traveling from Baton Rouge, so they also included a $300 “out of town” fee. That doesn’t account for the cost of their rooms at the Hotel Bentley, $742 in total. It would’ve been $712, but they decided to use the hotel’s valet parking.

The fire breather from Houston sent an invoice for $2,400. He didn’t bill by the hour or add on any travel fee, but he and his assistant both got free rooms at the Bentley as well. They parked their own car.

Alexandria paid the stilt walkers, the non-clown balloon artists, and the fire breather what they had requested, even though it is unclear how they spent their time once the city moved everyone inside on Friday night and then again on Saturday night. They could’ve been downtown, where they planned to be, performing their act at an empty riverfront amphitheater. Sure, it may have been lonely, but the weather wasn’t nearly as bad as people feared it could be.

According to a trove of public records obtained by the Bayou Brief, the last-minute decision by the City of Alexandria to replace its “signature event,” Alex River Fête, with an entirely new festival- the clumsily-named Alexandria Red River Festival- cost nearly twice as much than the $100,000 it had budgeted and resulted in a dramatic reduction in attendance.

The Bayou Brief would ordinarily upload the entirety of the records request as attachments; however, the documents provided by the City reveal un-redacted, private banking information for at least one of its vendors. Susan Broussard, the City’s Chief of Staff, refused to answer any questions or provide any comment.

Taken together, the records raise major concerns about what appears to be an extraordinary lack of oversight as well as serious questions about the legality of a substantial amount of public spending.

A contract employee hired as an office assistant in the Community Services Division signed checks and entered into contractual agreements on behalf of the city government. There were significant accounting discrepancies, which appear to vastly understate the cost of hiring the headline musical acts. And when asked specifically to provide copies of any ordinances or resolutions authorizing the Mayor to enter into contracts related to the festival, a city official affixed a handwritten note arguing, erroneously, that permission was unnecessary because the funding had already been “budgeted.”

A separate review of the minutes from the past year of council meetings reveals that the City never budgeted, requested, or received authorization for spending in excess of $100,000 for the festival. In fact, the City Council didn’t even officially recognize the event. It still hasn’t.

All told, however, the Division of Community Services approved invoices totaling $190,418.58. The records do not indicate how it spent $17,500 to pay a portion of the fees associated with four separate musical acts: Whodini, Jeremy Fruge, Midnight Star, and Jeff Bates. These costs do not include the price of labor from the public works department or police overtime for security, which in prior years amounted to approximately $30,000.

This year, Alexandria spent (or obligated itself to spend) more money on just music and entertainment than it had spent to host the entirety of three of the six previous Alex River Fête events, all of which attracted between two to four times as many people in attendance (and no, we can’t blame it on the rain).

The previous iteration of the festival had drawn in more than 15,000 to 30,000 people a year, rain or shine. This year, even according to the most generous estimate, over the course of three days, the Alexandria Red River Festival was attended by 6,000 people, 5,000 of whom showed up on Sunday.

If you live in Central Louisiana and haven’t heard of the festival, it’s understandable. Despite the fact the city spent nearly $27,000 in one month on advertising and promotions, primarily for radio commercials (including thousands of dollars for sponsored interviews and paid spots on the AM dial), it may have been too little and too late.

Among other things, it coughed up more than $1,500 to buy the web domain www.RedRiverFestival.com, which never ended up working. The website is dormant, just as it had been for the past fifteen years.

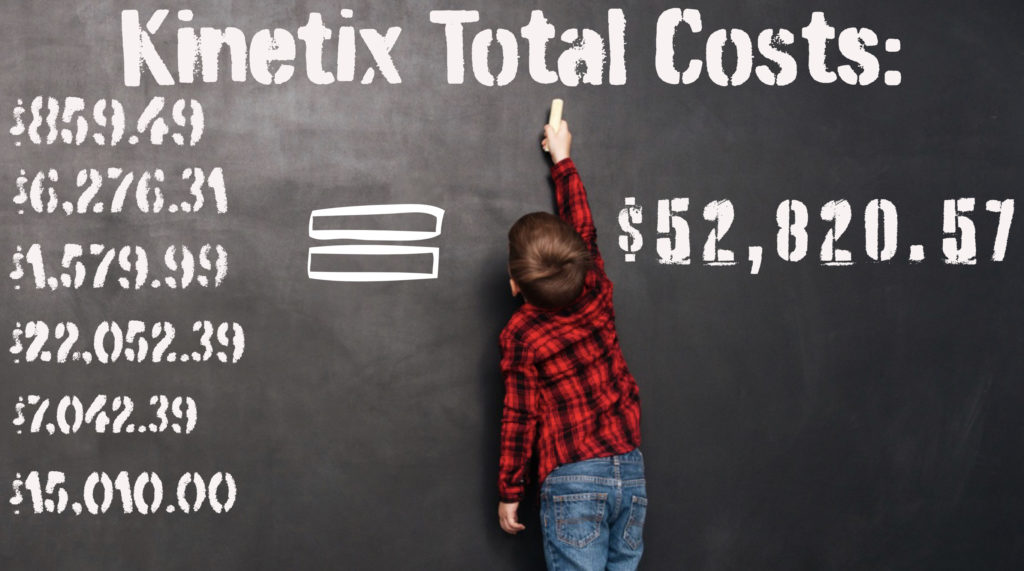

More than 25% of the expenditures- $52,820.57- went to a single company, Kinetix, a local website development and marketing firm.

Put another way, this year, the City of Alexandria paid Kinetix more money to assist in rebranding and marketing the Alexandria Red River Festival than the total amount it spent out of pocket six years ago to launch Alex River Fête, which was attended by twice as many people.

To be sure, some of the expenses from this year included pass-through costs. For example, Kinetix was actually responsible for purchasing that expensive web domain, and it appears there is a good reason they never got around to flipping the switch and turning the thing on: The domain wasn’t transferred to them until May 2nd, a day before the festival began.

For the purposes of full disclosure: Eight years ago, when I worked at Alexandria City Hall, I coordinated with Kinetix on multiple projects, and I believe they create exceptional, high-quality work. But they were being asked to rebrand something they had spent six years helping to build, and they were given less than two months and assignments that primarily should have been handled by city staff.

Still, it is difficult to take their effusive characterizations of the event too seriously. In a “media audit” they provided afterward, Kinetix includes a screencapture of a Facebook post they published and then paid to promote on the festival’s page about one of the musical acts, the band Whodini. “Everyone was so excited about seeing Whodini!” they claimed. All told, the post received 182 ”likes.” Not exactly reassuring.

Liz Lowry, the Kinetix employee who managed the project, declined multiple requests for comment.

During the past two months, eight credible sources with knowledge of decisions made concerning the event, all of whom requested anonymity, agreed to provide me with additional information.

Alexandria is a small city.

The decision to rebrand the festival had been made unilaterally and hastily by then-Director of Community Services Von Jennings. According to three sources familiar with the timeline, Jennings did not receive the permission or approval of Mayor Jeff Hall. She named it the Alexandria Red River Festival, they say, without consulting with any of her colleagues or even members of her own office. Hall, who took office in December, is the first African American ever elected mayor in the city’s 200 year history.

Jennings’ decision to spearhead a new event on behalf of Mayor Hall was met with swift public criticism, and on the final night of the festival, she lashed out on Facebook at a local waitress who made the benign and accurate observation that the Alexandria Red River Festival had been poorly attended, calling the woman “a racist piece of shit.” Under immense public scrutiny, Jennings was forced to resign two days later. She has not yet responded to a request for comment.

Notably, at no point during the campaign season did Mayor Hall or either of his two opponents discuss replacing its signature event, though candidate Catherine Davidson proposed changing its dates after New Orleans’ JazzFest.

When Alex River Fête launched in 2013, it was as a “conceptual test event” that could potentially replace Alexandria’s annual barbecue festival, Que’in on the Red, which had become beset by logistical problems and was constrained by its association as a circuit event for the Memphis in May competition. In that first year, the City spent $45,000, which was matched with a $45,000 donation from GAEDA, the local economic development authority. The “hard costs” actually incurred totaled approximately $81,000; the festival came in under budget, and attendance was right on target.

By the time Mayor Hall took office, the two Fêtes- River and Winter- were both on track to be self-sustaining if not revenue-generating events.

In a state in which the number of festivals is in competition with the number of days in a year, Alexandria had done something that had eluded it for decades: It had finally created a pair of brand name regional events that drew in tens of thousands of people, both in the late spring and in the early winter.

Unfortunately, it may be difficult, if not impossible, to pretend as if the Alexandria Red River Festival was just a rookie mistake. Within only a matter of three months, the City burned through more money than it was legally authorized to spend, but more importantly, it burned through the reservoir of goodwill that had taken more than six years to collect.

This year, the new festival failed to attract a single community or private-sector sponsor (though a handful of people who were paid for their services may claim they provided a “discount,” the documents suggest otherwise).

Now, that will be doubly hard to regain.

Particularly because one of the very first things the former Community Services Director did before hitting the reset button: She hit delete, and in an instant, evaporated the social media pages of the River Fête and, along with that, the ability of the City to message a note of apology to the tens of thousands of people who once cared enough to show up.