Former Gov. Kathleen Babineaux Blanco, the first woman to ascend to the summit of political power in Louisiana and whose tenure as the state’s chief executive was dominated by the devastation wrought by hurricanes Katrina and Rita, died today, August 18th, 2019, after battling an aggressive and rare form of cancer. She was 76.

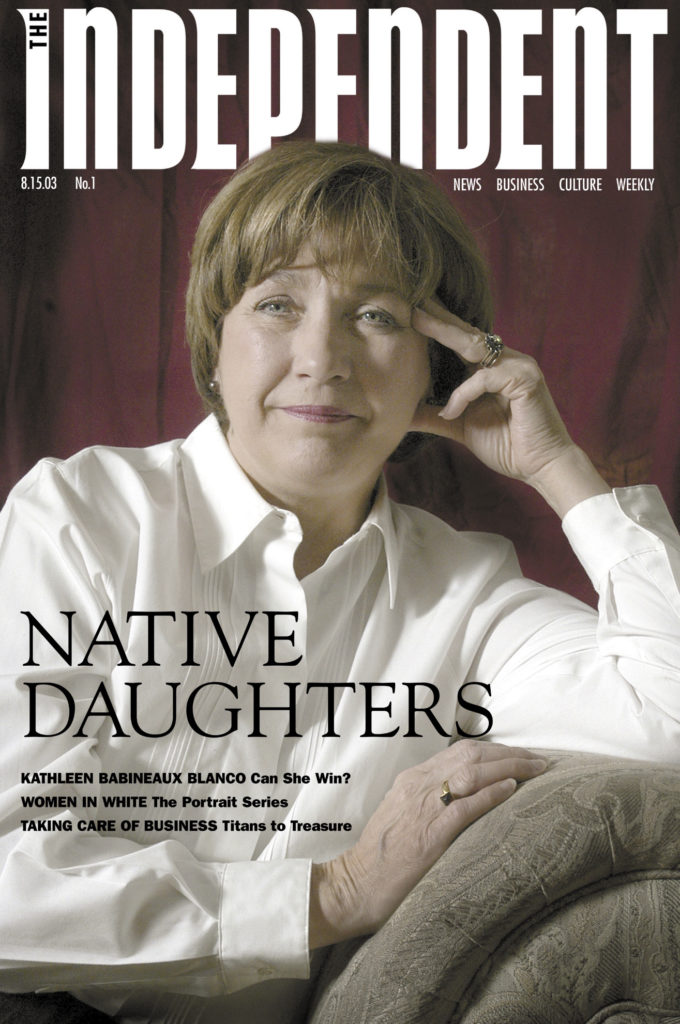

“At a time when few women ventured into the man’s world of government and politics, she just sashayed right on in to the middle of it all,” former U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu told the Bayou Brief in late 2017, shortly after Blanco publicly revealed her prognosis. “Louisiana is a better, more just place because of Gov. Blanco’s life of service.”

Her professional career, which she had placed on hold for nearly fifteen years in order to raise her six children as a stay-at-home mother, was a series of firsts: The first woman elected to represent Lafayette in the legislature, the first elected to the Louisiana Public Service Commission, and the first elected as governor.

And although her predecessor, former four-term Gov. Edwin W. Edwards, was often called the “Cajun Prince,” the truth is that Louisiana’s only Cajun governor since Alexandre Mouton left office in 1846 is Kathleen Babineaux Blanco. (Both of Blanco’s parents were descendants of settlers who had been forcibly exiled from L’Acadie, a region in what is now the Maritime Provinces of Eastern Canada).

Blanco, who opted not to seek a second term as governor, never lost an election.

Today, although the state’s two largest cities, Baton Rouge and New Orleans, are both led by women, every statewide and federal elected office is currently held by a man. All five Public Service Commissioners are men, and women comprise only 15% of the state legislature, none of whom are in leadership positions.

The seat Blanco once occupied in the state House of Representatives has subsequently and exclusively been held by male politicians. During the past four years, repeated attempts to pass equal pay legislation have failed, and a recent effort to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment was resoundingly rejected in the state Senate.

In 1984, Blanco, a lifelong Democrat, arrived at the state Capitol as a 41-year-old freshman, then one of only five women in the legislature. Her 29-year-old colleague, state Rep. Mary Loretta Landrieu, had just been elected to a second term. It may have seemed impossible to imagine then that, only twenty years later, the two women would become the top elected officials in the entire state, with Blanco serving as its governor and Landrieu as its senior United States senator.

In 2011, Blanco was diagnosed with ocular melanoma, but after six years in remission, the cancer had returned and spread to her liver. It was a monster, Blanco said.

The former governor had initially revealed her prognosis in a letter to the public in December of 2017, describing herself as being “in a fight for my own life, one that will be difficult to win.”

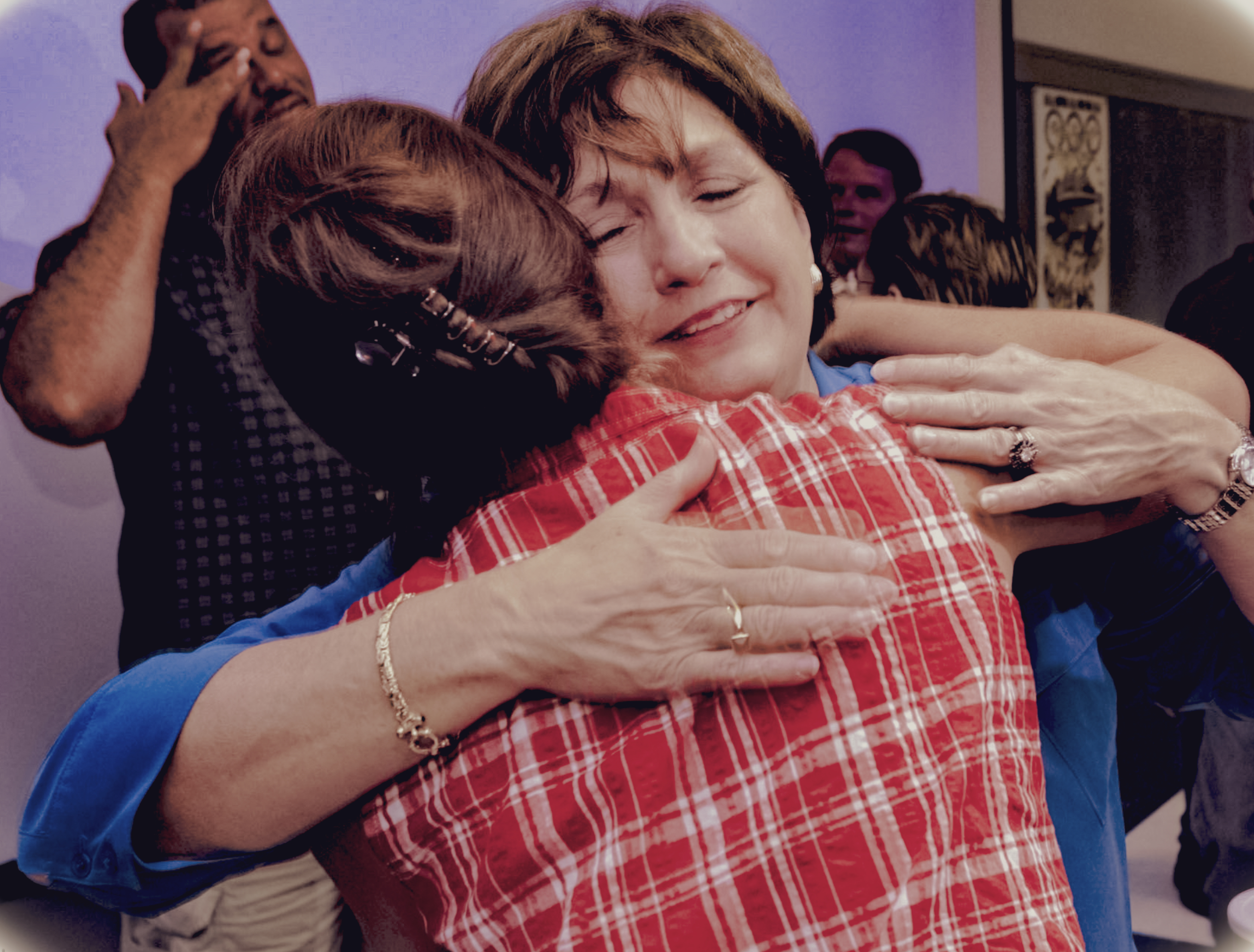

She was met with an enormous outpouring of support, and, for the first time since she left office in 2007, many of those who had assailed her actions in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina reconsidered her leadership. Only a decade prior, Blanco’s legacy had seemed irreparably tarnished by political operatives in the George W. Bush White House, who sought to deflect blame for the federal government’s negligence in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, and by former New Orleans Mayor C. Ray Nagin, whose flummoxed and unsteady leadership frustrated state and federal officials. Today, Nagin, who was subsequently convicted on 21 counts of wire fraud, money laundering, and bribery, is serving a ten-year federal sentence, while Blanco’s legacy has largely been vindicated.

“Gov. Blanco is now rightly acknowledged as the most underrated governor in Louisiana history,” James Carville asserted. “But that’s only part of the story. The truth of the matter is that she’s also one of the most underrated governors in modern American history.”

To those who knew her well, Kathleen Babineaux Blanco was generous but no-nonsense, confident but not braggadocios. She could be effusive with praise for her friends and allies and unsparing with criticism for her opponents. Her maternal, soft-spoken public persona belied her most important attribute: She was a shrewd and brilliant tactician. Along with her husband Raymond, she operated one of the most successful political operations in Acadiana history.

Kathleen Babineaux was born on Dec. 15th, 1942, the first of Leopold “Louis” and Lucille (Fremin) Babineaux’s six children.

She grew up in a sprawling Cajun, devoutly Catholic family in the hamlet of Coteau, Louisiana, located in Iberia Parish, approximately 15 miles south of Lafayette. Her father Louis, Sr. was a professional carpet cleaner. He passed away in February of 2001 at the age of 83. Her mother Lucille will celebrate her 100th birthday in October; two years ago, she renewed her driver’s license.

As a girl, Kathleen was first educated at Coteau Elementary, and at Mount Carmel Academy, a historic, all-girls school with a campus spread out over seven acres along the banks of Bayou Teche in New Iberia, where her family had relocated when she was fourteen.

Mount Carmel changed its name in 1987, but by the next year, the school had been forced to permanently shut its doors, only two years shy of the 100th anniversary of its inaugural graduating class.

After high school, she earned a bachelors in Business Education from the University of Southwestern Louisiana, now known as the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

On August 8th, 1964, Kathleen Babineaux married Raymond Sindo “Coach” Blanco, a school teacher and football coach originally from Birmingham, Alabama, at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic Church in New Iberia.

The couple met in May of 1962 at a high school graduation party Kathleen’s parents hosted in her honor. Coach was 26 at the time, fresh off of guiding the Catholic High School football team and Kathleen’s brother Kenneth to victory in the state championship. At first, Kathleen, then 19, didn’t think she had met the man she would marry, but Coach was smitten and persistent.

By the time he had worked up the courage to propose, Coach, now a defensive coordinator at USL (ULL), was strapped for cash, unable to afford an engagement ring. So, in order to pay for the ring, the couple told journalist Tyler Bridges in 2004, one night, Coach headed to the Tropicana Casino, in between Lafayette and New Iberia, and went on an extraordinarily lucky blackjack streak.

After six years coaching football, Coach would spend the remainder of his professional career working, in various capacities, as an administrator at the USL (ULL), retiring in 2009 as its Vice President of Student Affairs.

Kathleen Blanco also began her career in education, briefly teaching business at Breaux Bridge High School before the school forced her to quit once she became pregnant with her first child. She and her husband had six children, four daughters and two sons, and she put her professional career on hold for nearly fifteen years to raise their children as a stay-at-home mother.

Throughout her life, Kathleen Blanco never ventured far away from the land or the people who lived along Bayou Teche. She was particularly fond of a young artist her husband had taught in high school. As she often recalled, Coach had kicked the boy out of class one day for “doodling” in his notebook.

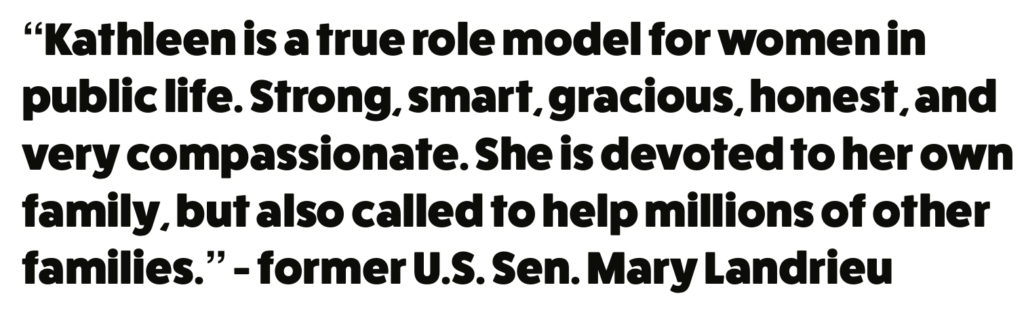

After debuting a series of works featuring his dog Tiffany painted in bright blue, George Rodrigue and his Blue Dog both became Louisiana icons. Once she was elected governor, Blanco commissioned him to paint her inaugural portrait, which she had displayed in the Governor’s Mansion, and, later, in the entrance to her home in Lafayette. Incidentally, one of Rodrigue’s important early works- which doesn’t feature his Blue Dog- is a painting of his mother’s 1927 graduating class at Mount Carmel Academy, which recently sold at auction for a record-shattering $152,500, the most-ever paid for one of the artist’s Cajun works.

In February, Blanco made what would be one of her final public appearances, alongside Gov. John Bel Edwards at the groundbreaking of the George Rodrigue Park in New Iberia and the dedication of the nearby Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Exhibit Hall, housed inside of the Bayou Teche Museum.

Shortly after qualifying to run for a second term, Gov. Edwards shared a video of Blanco’s endorsement, making her the first person to “officially” endorse the governor’s re-election.

After leaving office, Blanco donated her archives, said to include a draft of a memoir she wrote following her departure from public office, to ULL, which launched a public policy school named after Blanco last year.

Although Kathleen Blanco had previously volunteered to support J. Bennett Johnston’s 1971 unsuccessful bid for governor against Edwin Edwards and for Jimmy Carter’s 1976 presidential campaign, her first paid job in public service was with the United States Department of Commerce. After acing the Department’s exam, she was hired as Acadiana’s District Manager for the 1980 Decennial Census. It may have only a been year-long gig, but it provided her with invaluable, extensive insight into her community and the unique part of the country she called home.

Conducting the census is, in many respects, similar to running a grassroots political campaign. It requires administrators to manage an extensive canvassing operation, to reach out to marginalized populations, and to maintain a detailed inventory of demographic data.

Afterward, Blanco and her husband recognized an opportunity to use the insight she had gained during the census and his political instincts to assist candidates for public office, and together, they launched Coteau Consulting, a marketing and political consulting firm, which proved to be a launching pad for Blanco’s own ambitions.

While Coach, who had always been known as a savvy political operator, never sought the limelight, he proved to be a skilled, behind-the-scenes strategist and campaign manager who championed his wife’s career and nurtured a string of relationships with members of the media and the male-dominated business community. Last year, he was inducted into the Louisiana Political Hall of Fame in recognition for, among other things, his contributions to his wife’s undefeated record.

In 1983, the year former Gov. Edwin Edwards made his first of two extraordinary comebacks, the state featured what would easily become the most extravagant election its history, as chronicled in John Maginnis’ now classic book The Last Hayride. Louisiana was flush with revenue from a resurgent oil and gas industry, and the marque race between Edwards, a Democrat, and the Republican incumbent John Treen ended up raising more money, at the time, than any other non-presidential election in American history. Edwards obliterated Treen in the October primary, later celebrating his victory with a trip to Paris, along with 400 of his campaign supporters.

That July, four-term state representative J. Luke LeBlanc decided to surrender his seat in order to care for his ailing wife. It would be the first election in 27 years LeBlanc’s name wasn’t on the ballot, and Kathleen Babineaux Blanco would be the first to declare her desire to replace him.

She faced two other Democrats, Lafayette City Councilman Bob Domingue and attorney Stephen Spring, and one Republican, Jan Heymann, the wife of Herbert Heymann, then the wealthiest man in Lafayette. The Heymann family are generally credited with attracting the oil and gas industry to Lafayette, after Herbert’s father Maurice, a department store owner, developed the Oil Center complex.

Jan Heymann spent six times more as the other three candidates combined, and many had believed she would win the election in the primary. But Blanco upended the conventional wisdom, forcing Heymann into a runoff after trailing her by fewer than 1,000 votes. Blanco swiftly picked up the support of fourth-place finisher Spring, and local political pundits speculated that the candidate who received the endorsement of Domingue would likely win. However, after Domingue announced he was endorsing Heymann, the Republican, and not Blanco, the Democrat, there was speculation that he had been unduly pressured, which resulted in the unusual decision by Domingue’s wife and three daughters to place a full-page open letter in the local newspaper. Instead of putting the issue to rest, the letter only reinforced the perception that something was amiss.

In her first campaign, Blanco emphasized her support for increased funding for public education and for USL (ULL), much as she would do again in her campaign for governor.

It worked. In a low-turnout runoff, she won by a ten-point margin, much to the surprise of Heymann, who had believed the election was much closer than it proved to be.

When she sought re-election in 1987, J. Luke LeBlanc attempted to come back from retirement, but by then, Blanco had earned a reputation as an effective and impressive legislator. She won again by ten points.

Buoyed by her strong showing, Blanco almost immediately set her sights on a different office, a six year-term on the Public Service Commission, the five-member elected body that regulates utilities. She squared off against three opponents, including “Skip” Hand, a Republican colleague who represented Jefferson Parish in the legislature. Blanco finished ahead of Hand in the primary but not enough to secure an outright victory.

In November of 1988, she beat him by nearly 41,000 votes, becoming the first woman elected to the position. Hand would subsequently become an elected judge, and Jerry LeBlanc, the son of former state Rep. Luke LeBlanc, took back his dad’s old seat in the legislature, which he would hold for a record five consecutive terms.

When Blanco sought re-election to the Public Service Commission in 1994, no one bothered to run against her, and once again, she decided to set her sights higher.

In 1995, Mary Landrieu, now state Treasurer, was widely considered to be the favorite in the race for governor. Landrieu had sufficiently distanced herself from outgoing Gov. Edwin Edwards, and, although she was only 39, the only other candidate who could match her experience was former Gov. Buddy Roemer, who had managed to squander his political base and upset members of both political parties when he defected from the Democratic Party and became a Republican in 1991, the final year of his first and only term.

But Landrieu’s bid for governor became complicated by back-room political shenanigans. Democratic state Sen. Murphy “Mike” Foster, the grandson of former Louisiana Gov. Murphy Foster, had also declared his candidacy, but after failing to gain traction, he made a last-minute decision to qualify as a Republican. U.S. Rep. Cleo Fields, an African American Democrat who had only been elected to Congress a year before, was encouraged to run by allies of Gov. Edwards, many of whom resented Landrieu’s criticism of the outgoing administration. And finally, Melinda Schwegmann, the sitting lieutenant governor and a Republican from a well-known New Orleans family, decided to throw her hat in the ring, despite both her and her husband privately vowing to Landrieu that she would not become a candidate.

Blanco, who had always enjoyed a warm relationship with Landrieu, dating back to her first term in the legislature, decided to take advantage of the down-ticket opportunity and campaign for lieutenant governor.

Ultimately, Landrieu would fall short of the runoff by less than 1%; Schwegmann, who captured slightly more than 71,000 votes, proved to be an effective spoiler, setting up a runoff between Fields and Foster. The newly-minted Republican would win by a margin of more than 400,000 votes.

Meanwhile, Blanco, who faced a crowded field that included Republican state Rep. Suzanne Mayfield Krieger and Democratic state Rep. Chris John, easily coasted into the runoff, finishing first in the primary with 44% of the vote and subsequently winning a runoff against Krieger with nearly the same margin as Foster had captured at the top of the ticket.

When she ran for reelection in 1999, Blanco faced only symbolic opposition. She won again, this time with 80% of the vote, and again, she set her sights higher.

Shortly before he took the Oath of Office, Gov. Mike Foster became aware of a 24-year-old McKinsey consultant and Rhodes Scholar originally from Baton Rouge who had submitted, on his own accord, a policy white paper on reforming health care in Louisiana. The young man had also sent his paper to the other leading Republican candidate, former Gov. Buddy Roemer, but after Roemer was vanquished in the primary, Bobby Jindal knew he only had one man he needed to convince.

Foster appointed Jindal as the state’s Secretary of Health and Hospitals, and, at 24, he easily became the youngest cabinet member in Louisiana history. Jindal wouldn’t last long in the job, but Gov. Foster had taken a keen interest in nurturing the young man’s ambitions.

Jindal would not rise through the ranks the same way as Blanco had, yet in 2003, as Foster’s second term headed toward an end, they faced one another in a gubernatorial contest that seemed like a political science experiment: A white Democratic grandmother squaring off against a 33-year-old Indian-American Republican man.

First, though, Blanco had to contend with two other well-known Democrats, state Attorney General Richard Ieyoub and former Congressman and political party broker Buddy Leach. And among those three, it was anyone’s guess who would prevail.

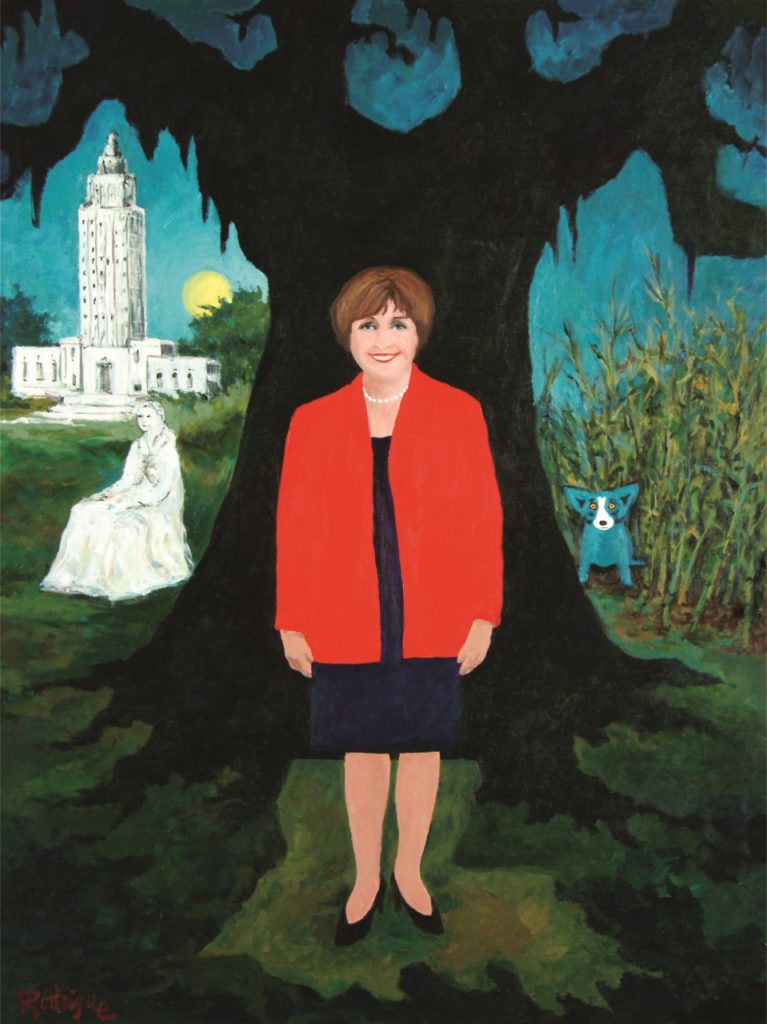

That August, Steve and Cherry May, the former owners and publishers of The Times of Acadiana, were putting the finishing touches on the the debut edition of their new publication, The Independent, a colorful, forward-thinking news magazine covering Acadiana. They decided to make a bold statement and take a risk: Selecting Blanco as the subject of their very first cover story. It may seem like the obvious decision in hindsight, but at the time, Blanco, despite all of her previous successes, was not expected to win.

Given the dynamic, Jindal, the only competitive Republican, could coast into the runoff, and in the October jungle primary, he did just that, easily securing first place and garnering 33% of the vote. Blanco, on the other than, narrowly snuck into second place, besting Ieyoub by fewer than 17,000 votes and Leach by 73,000. All told, she captured second place by receiving only 18%. To her supporters, it seemed like a miracle. The Independent, however, seemed prescient. Their cover article was titled “Can She Win?”, and the answer to that question, increasingly, looked more like a yes. Or at least a definite maybe.

There had been a fear, maybe even an assumption, that the runoff election between Jindal and Blanco would be poisoned with racism by some and misogyny by others, and while there is no question that race and gender were both a part of the story of the election, various studies on media coverage and voter perceptions reveal they weren’t much of a factor.

Republicans were genuinely enthusiastic about Bobby Jindal, who presented himself as a fast-talker and a nimble thinker and who spoke frequently about cleaning up public corruption and changing the state’s image. However, despite his meteoric rise in government, Jindal’s experience was still limited, and Blanco had a command of a much wider range of issues. Like Jindal, she had also worked on health care policy, when she was a member of the legislature, and although Jindal was once briefly the President of the University of Louisiana system, no other elected official in the state was as closely associated with ULL as Blanco, who was a teacher and was married to a teacher. And unlike Jindal, Blanco had worked on utilities regulation as a Public Service Commissioner. She’d spent the previous eight years leading the state’s Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism, which meant she had constantly been traveling across the state. By her estimate, she had been to Shreveport, for example, more than 130 times.

Still, the Republican Party was resurgent in Louisiana; with only a week before Election Day, polling had suggested Jindal was on track to narrowly eek out a victory. That changed in a matter of seconds, though, during the waning moments of the final televised debate, held in New Orleans only three full days before the polls opened.

Blanco and Jindal had already debated twice before, and given the unique dynamic at play, the contest had generated a significant amount of national attention. Their previous debate, hosted by Centenary College in Shreveport, was broadcast live on C-SPAN.

When the moderator asked each candidate to name a personal experience that helped define their life, Jindal was up first, beginning with a reflection on the birth of his first son before pivoting to a clumsy answer about Christ finding him, which may have unintentionally reinforced the perception that his surplus of ambition was offset by a dearth of humility and awkwardness.

Blanco’s answer, however, made for the most powerful moment of the entire election. Even before she began speaking, it was obvious the question- and her answer to it- had called on her to reflect on a source of profound sadness.

“The most defining moment in my life came when I lost a child,” she said haltingly. It was the first time she had spoken publicly about the loss of her son Ben since she delivered his eulogy six years prior, and anyone who tuned into the debate that night witnessed the election turn in Blanco’s favor in matter of seconds.

On Nov. 15th 2003, Blanco was elected Louisiana’s 54th Governor, defeating Bobby Jindal, the 33-year-old Republican wunderkind, and becoming the first woman ever to hold that position. Raymond Blanco’s friends and family members would now call him “First Coach.”

Blanco proved to be an ambitious, tough-nosed governor who, as was custom, yielded tremendous power over the legislature. Her priorities were straightforward: expand affordable health care, invest in higher education, and attract jobs by improving the state’s infrastructure.

However, Kathleen Blanco’s term as governor will never escape the shadows left in the wake of hurricanes Katrina and Rita, back-to-back catastrophes that were exacerbated by what seemed like willful incompetence by local officials and a presidential administration intent on exacting political retribution as a way of deflecting from their own negligence.

Earlier this year, after it was announced she had begun hospice care, Blanco received a phone call from former President George W. Bush.

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the president pressured Gov. Blanco to turn over her command of the National Guard to him, a proposal attributed to Karl Rove, his longtime political “architect,” and White House Chief of Staff Andy Card.

Blanco, whose approach to governance was sometimes belied by her low-key, even-tempered tone, knew how to battle against bullies, and had believed the White House’s proposal to be nothing more than a political stunt. “You guys are now trying to come in and save face,” she told Card. “I’ve got thousands of people here in the trenches while you play your politics.”

The White House escalated the stakes, threatening to invoke the Insurrection Act under the pretense of restoring order. Blanco called their bluff. “You go ahead and declare the Insurrection Act and take it over that way,” she told Card, according to Peter Baker’s Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House. “I’m going to go out and say that you all care more about politics than saving lives.”

Ultimately, Bush ruled against what would have been an unprecedented usurpation of state authority. Today, at his presidential library at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, an interactive exhibit called the Decision Points Theater prompts visitors to determine whether they would have reacted similarly.

Two days after Katrina hit, James Carville phoned Blanco’s press secretary Bob Mann. “Get ready,” he told Mann. “The White House is starting to put the blame on you guys. It’s going to get ugly.”

Carville was right. A day after his warning, Mann read a report in The Washington Post asserting Gov. Blanco had not yet declared a full emergency warning. The governor had actually made the declaration three days before the storm.

Gov. Blanco instructed her staff not to fall into a political trap.

“From the beginning, Gov. Blanco emphatically forbade anything that could be interpreted as an attack on President Bush,” Mann writes.

“We are going to need this president to help us rebuild this state,” she told her staff, according to Mann.

“Let them politicize this storm,” Gov. Blanco said, “We’re not going to do that.”

Her Republican critics ridiculed her for being too emotional, labeling her “momma governor,” a characterization that was brazenly, if not purposely, misogynistic. Among Democrats, however, Blanco remained widely admired. According to at least one survey conducted after Katrina, 70% of residents blamed President George W. Bush for the government’s failed response.

When Blanco left office, forgoing a campaign for a second term, she had the lowest approval numbers of any governor in state history, an ignoble record from which her successor would mercifully unburden her.

In the decade between Blanco’s departure and her diagnosis, her decisions as governor have been largely vindicated or, at the least, forgiven by a public that now has the benefit of hindsight. Since the Civil War, no other governor in America had ever been forced to confront such a chaotic and disastrous set of circumstances.

“Ten years ago I wrote an especially mean column about Kathleen Babineaux Blanco,” the Times-Picyaune‘s former columnist Jarvis DeBerry acknowledged in a remarkable and moving confession. “I attacked her for sport. I mocked and belittled her unnecessarily, and when I look back at what I wrote, I feel ashamed.” DeBerry echoed the sentiments of many in Louisiana.

“I always thought history was a little boring,” she joked last July in an interview announcing the founding of the Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, “because it was hard for me to identify… with all of the men we studied about.”

In addition to the public policy school hall in Lafayette and the exhibit hall in New Iberia, this January, the lobby of the Superdome in New Orleans was also renamed after Blanco, who was instrumental in securing the funding to repair and renovate the iconic building after it was significantly damaged following Hurricane Katrina.

Kathleen Babineaux Blanco made her final appearance in public on July, 2nd, attending a signing ceremony of Senate Bill 134 hosted by Gov. John Bel Edwards in Lafayette.

“I do love all of the people of Louisiana,” she told the audience. “I ran to serve everyone. My life has been so charmed. God puts you where he wants you to be.”

The bill renamed a portion of Highway 90 from Lafayette to Raceland.

The Governor Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Highway runs parallel to the tiny hamlet of Coteau, stretching alongside the banks of Bayou Teche.