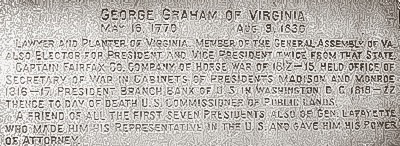

George Mason Graham, the so-called “father of LSU,” had a name that opened doors.

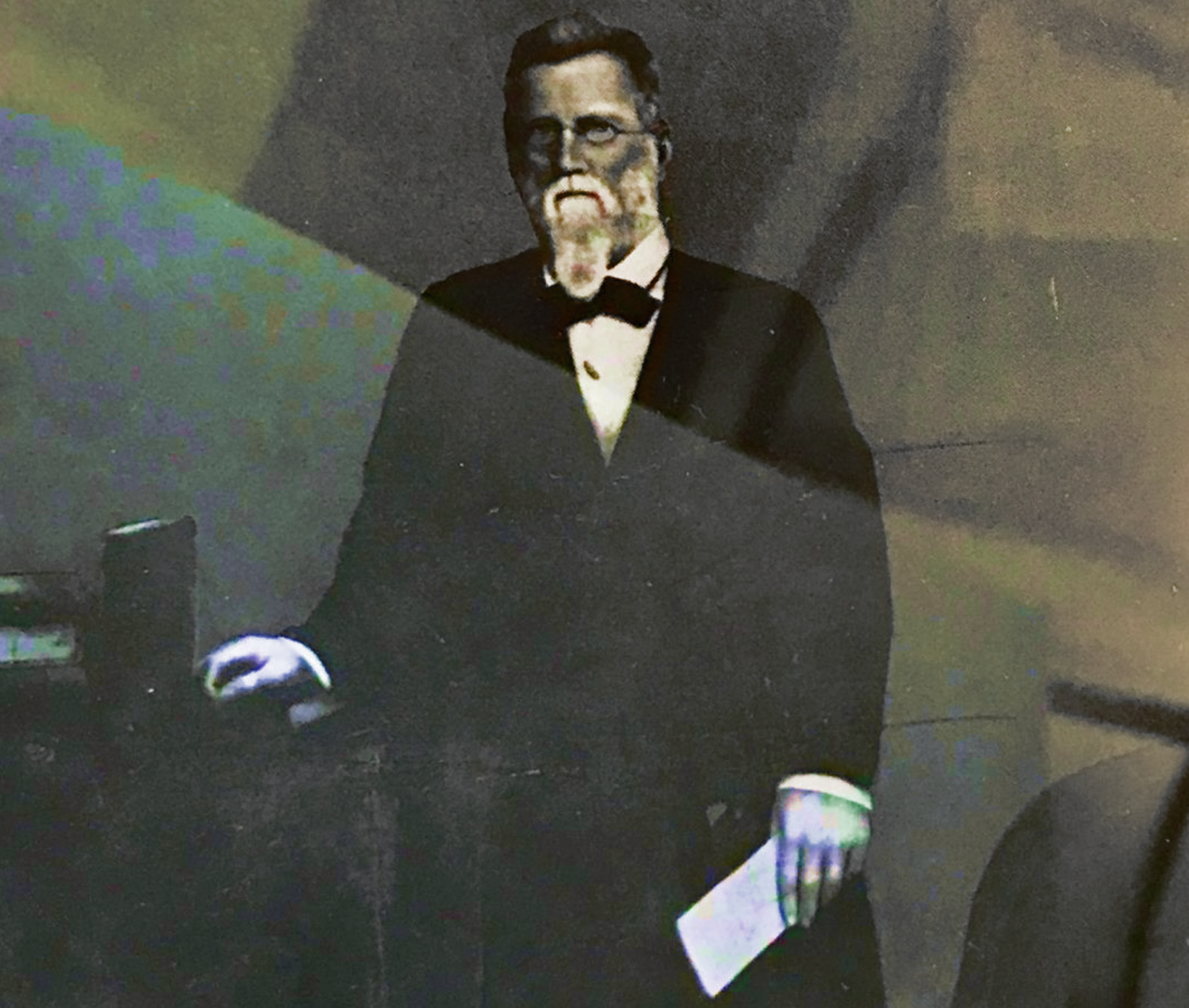

Yet today, despite his central role in establishing the state’s flagship university, there is very little scholarship on Gen. Graham of Tyrone Plantation. You won’t find his name on the school’s Wikipedia page. The $4.1 million residential hall that had been named in his honor in 1958 was quietly demolished about a decade ago. In 1980, in an art heist that remains unsolved, the only known full-length portrait of Graham was stolen, cut off of its frame and removed from the walls of LSU’s David Boyd Hall.

Even though there are affiliated campuses in Alexandria, Eunice, and Shreveport, LSU- as a brand- is now inseparable from Baton Rouge. The university is at the core of the city’s cultural, social, economic, and political identity. But LSU actually began in the piney hills of northern Rapides Parish, 2.5 miles away from Louisiana College, a tiny private school that squandered its academic reputation after a faction of far-right Southern Baptists hijacked its leadership 14 years ago. Aside from a few historical markers, some wooden benches, and a picnic table, LSU’s original campus is now only a couple of acres of otherwise unremarkable vacant land next to the VA Hospital.

For most of my life, I’ve been fascinated by the complicated history of Rapides Parish, the land where I was born and raised. My interest is partly because Rapides and its parish seat, the city of Alexandria, had once seemed poised to become the state’s second-largest metropolitan area and economic engine before it was decimated during and then in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Some believe Interstate 10 serves as the unofficial line of cultural demarcation in Louisiana, but in my opinion, the real border is the Red River, which slices through the state, splitting both Shreveport and Bossier City as well as Alexandria and Pineville before wandering into the Atchafalaya and connecting with the Mississippi. Alexandria is located in the geographic center of Louisiana, in a region that is both literally and figuratively the crossroads of the state.

On the other side of the Red River, across from Alexandria, the landscape changes dramatically: Cypress and swamp are replaced by pine and rolling hills; Baptists outnumber Catholics; country dethrones jazz and zydeco; food is fried, not boiled, and French is a foreign language spoken in a distant land.

Admittedly, my fascination with the history of Rapides Parish is also driven by curiosity about my own genealogy; my father’s family has been in Rapides Parish for at least five generations, mostly arriving in the early 1850s, the same time a wealthy Virginia-born planter living on the banks of Bayou Rapides began charting out his vision for a new public university.

In addition to his own autobiography and the genealogical work of his descendants, Mason Graham, as he was known, is the subject of only one serious work of academic scholarship, which was published in 1969 and, unfortunately, contains a handful of glaring factual errors. During the past three weeks, I’ve consumed just about everything one can find out about Mason Graham, and the portrait that has emerged is of a man beleaguered by tragedies, haunted by his family’s legacy, and animated by both the good and the evil of his young country. He was a thoughtful, intelligent, and generous man to his friends and colleagues, but he was also a virulent racist who saw no contradiction between his support of slavery and his belief in the high-minded aspirations about equality, justice, and freedom that breathed life into a new nation.

No doubt, there will be those who disagree with my characterization of Mason Graham. I do not find any value in sentimentalizing the antebellum South or in conveniently overlooking the horrors of slavery, nor do I find it credible to promote the pernicious belief that slave owners should be understood merely as “men of their time,” as if they were just victims of circumstance.

Given the recent efforts across the American South to reconsider the ways in which municipalities and public institutions contextualize their historical ties to slavery, the Confederacy, and the Lost Cause, it should not be too surprising that there’s been renewed attention to a remarkable irony about Louisiana’s flagship university: Its very first executive (then known as a superintendent, once known as a chancellor, and now known as a president) was Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. While Sherman remains one of the most consequential and controversial leaders in American history and the subject of countless biographies, LSU would not exist today if not for the other general.

“If you know your LSU history, you know that George Mason Graham was the glue that held the university together after the Civil War,” Henry Bacot, the long-time Director of LSU’s Museum of Art, told the Daily Reveille two years ago. Professor Bacot’s assessment is accurate, but Mason Graham was also much more than the glue that held LSU together during Reconstruction. He was the singular force that assembled the school’s creation.

Yet Graham has largely been relegated to the footnotes. Perhaps this is due to a dearth of scholarship. Perhaps it is also because his extraordinary contributions to the school are complicated and undermined by his hypocritical support of slavery. 154 years after the Civil War, we continue to grapple with how to tell the story of America’s original sin, and according to polling, even today, nearly half of the country believes monuments that glorify Confederate leaders should remain in the public square, despite their gross distortion of historical truths and the numerous ways in which they communicate oppression and hatred to racial minorities.

But you cannot tell the story of Louisiana without also confronting the horrors of slavery, and you cannot tell the story of LSU without also confronting the good, the bad, and the ugly truths about the school’s father, Mason Graham.

George Graham’s Son

His name was his mother Betsey’s idea, a way of honoring her late husband, former Secretary of War George Mason V., who died in 1796 on his 43rd birthday. Betsey was just 28, widowed with six small children. Seven years later, she married another man named George.

Although he lacked a famous surname, George Graham, a lawyer with whom she would have four more children (two of whom died in infancy), eventually became one of the young country’s most distinguished public servants.

He had briefly served as the nation’s Acting Secretary of War, under both President Madison and President Monroe, the same job as Betsey’s late husband had held. Graham helped transform West Point into both an academic institution and military academy, and he ironed out the details of a treaty with Spain that recognized the Sabine River as the border between Texas and Louisiana. After the Department of War, he served four years as President of the Washington, D.C. branch of the Bank of the United States, and after the bank, he was appointed as the nation’s Commissioner of Public Lands. When he passed away in 1830, he was remembered as a friend to all seven U.S. Presidents and as the legal representative of the Marquis de Lafayette.

The Masons, though, were one of America’s first family dynasties.

Betsey’s former father-in-law, George Mason IV, had been a Founding Father, a contemporary, childhood friend, and neighbor of George Washington, and the author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, the document that formed the foundation of the Bill of Rights in the U.S. Constitution. In fact, Mason was also one of three delegates to the Constitutional Convention who refused to sign onto the document, which he believed needed to be amended to include an itemized list of guaranteed rights and a repudiation of slavery (despite the fact that he was himself a slave owner). In 1792, as George Mason IV was on his deathbed, Thomas Jefferson traveled to Gunston Hall, Mason’s home in Fairfax County, Virginia, to say farewell and pay his respects.

There were only a handful of families as well-known- the Taliaferros, the Lees, the Randolphs, and the Townsends- almost all of whom were also from Virginia. Although he wasn’t technically a member of the Mason family dynasty, Mason Graham had been born into the rarefied air of the American aristocracy.

Betsey gave her son a name that opened doors, but it also left him big shoes to fill, with a foot in two extraordinarily accomplished families.

After Betsey’s tragic death in 1814, George sent their seven-year-old son Mason and their young daughter Mary to live with his brother John, an assistant to then-Secretary of State James Monroe. (Mary would later become a highly-respected nun, Sister Mary Bernard of Georgetown).

George decided to go “into the field” as a captain, to investigate the “Napoleonic exiles” that had established Champ d’Asile, a French armed settlement in southeast Texas, earning the distinction of being the first-ever “Anglo-American” to travel to the area. On that tour, Captain Graham met Jean Lafitte, “the notorious smuggler” who was then living like a king in Galveston; apparently, he received some commitments from Lafitte to recognize the United States’ authority in the neighboring Louisiana territory.

As a kid, despite his father’s absence, Mason had received a stellar education: Small private schools in Georgetown and Washington, D.C., and then a coveted spot at the military academy George had helped to transform: West Point. (He received his “warrant” to attend West Point from Vice President John C. Calhoun). Mason didn’t last long there, ostensibly due to his poor eyesight, and he transferred to the University of Virginia. In 1828, instead of returning to UVA for his junior year, 21-year-old Mason dropped out of college and moved a world away, to Rapides Parish, Louisiana.

Years before, his father had purchased a cotton plantation there, and Mason was tasked with overhauling its operations. It’s likely he had been sent to Louisiana- more than 1,100 miles away from his hometown- as a temporary assignment. At the time, Mason was aimless, having flunked out of two schools and appearing to have very few prospects as a military officer.

Today, Fairfax, Virginia is home to George Mason University, now the largest four-year school in the Commonwealth. But a century before George Mason University opened, Mason Graham had spearheaded the creation of a different school, a small seminary and military academy in Pineville, Louisiana that eventually moved to Baton Rouge and changed its name to Louisiana State University.

“Ranaway”

Mason Graham wasn’t the founder of LSU; the state legislature was. Yet LSU, as an institution, would likely not exist if Mason Graham hadn’t moved to Rapides Parish, Louisiana. And Mason Graham wouldn’t have ever moved to Rapides Parish if the slave trade had been illegal.

Six years after he arrived, Graham returned to Virginia, got married, and brought his new wife and his sister, Sister Mary, back to Louisiana. By then, he had owned his own plantation near Cotile Landing, in what is now the town of Boyce. A year later, in 1835, his young bride died after giving birth to the couple’s first child. A month later, the infant passed away.

“This left Mr. Graham in a restless, objectless condition,” the Daily Picayune later reported, “and under the influence of this spell he sold his plantation and returned to Washington.”

He came back for good in 1842, purchasing Tyrone Plantation on the banks of Bayou Rapides, a few miles outside of Alexandria.

At the time, an astonishing 74% of those living in Rapides Parish were enslaved African Americans. There were more slaves in Rapides Parish- over 15,000- than anywhere else in the state.

Graham quickly reasserted himself as a prominent planter and civic leader. Indeed, even though he had been “rambling about” until his return in 1842, he never severed his ties to Louisiana. In 1839, he served as the state’s one and only Whig delegate at the party’s presidential convention, supporting- to no avail- the candidacy of Henry Clay.

In 1843, a year after moving into Tyrone Plantation, Mason Graham organized a militia group, the Rapides Horse Guards, which, by all accounts, was essentially a precursor to the Ku Klux Klan. The Rapides Horse Guards was formed for only one purpose: To prevent an insurrection by terrorizing and inflicting violence against black slaves.

Three years later, as the nation became embroiled in the Mexican-American War, Graham refashioned his militia as a volunteer military regiment, and because he had briefly attended West Point and had organized the Rapides Horse Guards, he was named as its captain. Even though his company spent only three months in Mexico before being sent home to Louisiana, Mason Graham stayed put and saw action as the aide de camp to Col. John Garland during the Battle of Monterrey.

At the age of forty, with his military credentials finally firmly established, Mason Graham went back to his family at Tyrone Plantation.

Graham was born into privilege, but slave labor and cotton made him independently wealthy.

By 1860, he was worth the equivalent of at least $6.1 million. It’s unclear, however, if he ever possessed more than twenty human beings at any point, but there is very little doubt that Mason Graham was capable of horrific cruelty, despite his reputation as a “high-toned gentleman” and his fierce opposition to secession.

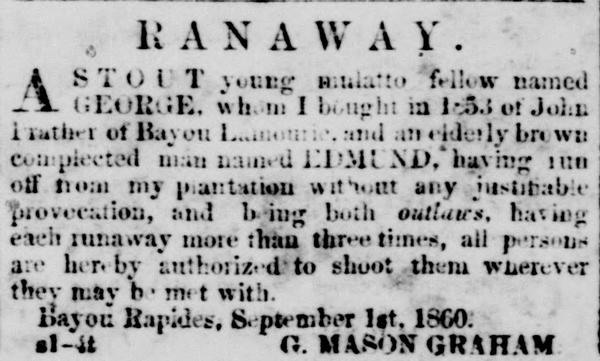

In September of 1860, he took out a classified ad, announcing that anyone who encountered “an elderly brown complected man named Edmund” and a “stout young mulatto fellow named George,” two slaves who had runaway from his plantation “without any justifiable provocation,” were authorized to shoot and murder the men “wherever they may be met with.”

We may never know the fates of Edmund and George, but when they fled Tyrone Plantation, Mason Graham was already beginning to panic about his own future and the future of his proudest accomplishment, the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy.

After nearly seven years of false starts, including a series of engineering failures that required a complete rebuild, the school had finally opened its doors in January, but as the nation prepared for a presidential election, Mason Graham recognized the inevitable: The union would break, and along with it, so too would his young school.

Esto Perpetua

On Jan. 18th, 1861, William Tecumseh Sherman, superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy, sent Gov. Thomas Overton Moore a letter of resignation.

“I accepted such position when Louisiana was a state in the Union, and when the motto of this Seminary was inserted in marble over the main door: ‘By the liberality of the general government of the United States. The Union — esto perpetua,’” he wrote.

Although he had served for only a year, Sherman was widely admired by the Board of Supervisors, including Gov. Moore, a staunch secessionist. Like all but one other member, Gov. Moore was from Rapides Parish and had been an enthusiastic supporter of the school well before he was elected governor.

For most of the 19th century, higher education was virtually non-existent in Louisiana. There were a small handful of private schools. A couple of Harvard-educated professors opened the College of Rapides in Alexandria in 1824. A decade later, in 1834, seven physicians in New Orleans founded the Medical College of Louisiana, which was ostensibly a public school even though it received barely any public support. “Although the Territorial Legislature in 1805, and, later, the state legislatures, attempted to provide for public education, the effort was mostly on paper,” Sue Eakin explained. “The legislature made provisional grants to these private academies requiring a certain number of indigent students be allowed to attend the school. There is no evidence that this was carried out.”

The Medical College of Louisiana subsequently rebranded itself as a part of the University of Louisiana, which was created, at least on paper, in 1847, at the same time the legislature also authorized a search for the land they needed to construct an entirely new public university. It took them five years to decide on land three miles north of Alexandria, across the Red River, in an area that would one day be known as the town of Pineville. (After closing down during the Civil War, the University of Louisiana eventually reopened as a private university named in honor of its benefactor, Paul Tulane).

Mason Graham was appointed by Gov. Paul Hébert as Vice President of what was then called the Board of Trustees in 1853, but because the governor was, by statute, the president of the board, Graham was effectively its leader. (While Gov. Hébert had appointed Graham, the decision to locate the school in Pineville was made by Hébert‘s predecessor, Gov. Joseph Marshall Walker, who owned a plantation in Rapides Parish).

While the legislature may have had little appetite for funding the University of Louisiana, they believed in Mason Graham’s vision for the school in Rapides Parish. The state sank money into building the new campus. It’d take another decade before the main building was finally erected, only to be deemed structurally unsound by two engineers working for P.G.T. Beauregard. But for a number of reasons, state lawmakers and the school’s leaders were determined.

Antebellum Rapides Parish was at the epicenter of the state’s cotton industry, which meant it was home to both a small number of wealthy and enormously powerful white planters and a massive population of enslaved African Americans. Not surprisingly, this made men like Mason Graham paranoid, especially as the practice of slavery became increasingly less tolerated nationally and Northern and Western states and territories began banning slavery within their borders.

Graham wasn’t just concerned about the possibility of a mass insurrection; he was also concerned about the younger generation of white men. They were lazy, he thought. Undisciplined. They lacked a work ethic and had been spoiled by inherited wealth.

When the Board of Supervisors convened their first meeting at Tyrone Plantation, they were divided about what kind of school they would open. Some argued in favor of emulating the University of Virginia, where Graham had spent two listless years. Others, including Graham himself, believed in following the example of another school in Virginia, the esteemed Virginia Military Institute. Only a military academy could guarantee the kind of rigorous discipline Graham had believed to be in desperate need.

Mason Graham ultimately prevailed. A military academy, it turned out, would be significantly cheaper to operate than a traditional four-year university, and Graham already knew exactly the person who should lead the new school. He had worked his contacts in the Department of War and received a glowing recommendation from Gen. Don Carlos Buell for a 39-year-old lawyer and banker who had served under him during the Mexican-American War. His name was William Tecumseh Sherman, and as Graham soon discovered, he had also served under Gen. Roger B. Mason, Graham’s half-brother.

Sherman and Graham would enjoy a unique and lifelong friendship, exchanging countless letters both before and after the Civil War. Even though he was the only Northerner on the school’s staff and his brother John was an ambitious Republican congressman from Ohio who opposed slavery, William Tecumseh Sherman was trusted by the men who had hired him to run Louisiana’s new military academy. After Abraham Lincoln was elected and the secession became a reality, Sherman tendered his resignation. He’d tried to resign once before, after a job opportunity in London seemed too good to pass up. Mason Graham begged him to stay.

This time, though, Graham made little effort to change his mind; he respected Sherman as a man of principle, and he deeply opposed Louisiana’s decision to secede, believing that the state could reach some sort of compromise with its northern neighbors.

With Sherman gone, the Louisiana State Seminary and Military Academy suspended classes, and its cadets became Confederate soldiers.

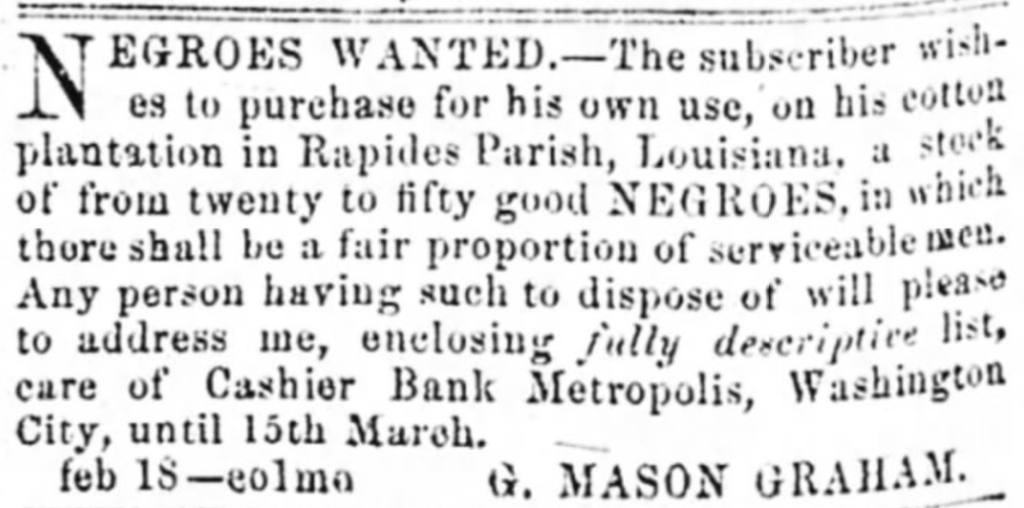

A month later, Mason Graham took out another classified ad:

Conflagrations

William Tecumseh Sherman and Don Carlos Buell, the man who recommended him for the job in Louisiana, became national heroes during the Civil War, fighting to preserve the Union that Mason Graham’s father and the family of his namesake, the Masons, had helped to create. Mason Graham lost nearly everything.

His home at Tyrone Plantation had been spared, but his cotton fields were burned to the ground and his cattle was either killed or set loose. He lamented the destruction in his autobiography, writing in the third person. “His (Graham’s) gin and 600 barrels of cotton and all of his barn burned. His corncribs full of corn and all others of his foodstuffs stolen, along with his horses, mules, and oxen. His cattle, hogs and sheep slaughtered, and his slaves gone,” he wrote.

He began the decade with a fortune worth the equivalent of at least $6.1 million, and he ended it with less than $160,000 in assets.

George Mason Graham officially earned the rank of “general” in 1867, though he had been elected as a Brigadier General by his company in Rapides and Avoyelles Parishes following the Mexican-American War. While horseback riding with his wife, Graham suffered a horrific injury that rendered him paralyzed. Gov. James Madison Wells, who was also from Rapides Parish, named him an Adjutant General of the State of Louisiana.

In May of 1864, Union Gen. Nathaniel Banks burned down the city of Alexandria. It would take two decades for the city to rebuild.

The school in Pineville was left alone, and on Oct. 2nd, 1865, it reopened under Superintendent David Boyd. Four years later, though, on Oct. 15th, 1869, the main building of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy (it was already being referred to as Louisiana State University, though the name wouldn’t be official until the following year) caught fire. It was a total loss.

By then, Mason Graham had receded into a nominal role on the state school’s Board of Supervisors. He had been spending more time back in his native Virginia, where he was free to vote for a Democrat. Against his will, he had been nominated to run for Congress in what was then Louisiana’s Fourth District. He made it abundantly known he was not interested in the job and lost an election in which he had never campaigned.

In 1878, he came back to Tyrone Plantation for good, for the second time in his life. He re-immersed himself into the school, which had swiftly been relocated into the former home of the State Institution for the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind. It was supposed to be a temporary move, but despite the best efforts of those in Rapides Parish, LSU would remain in Baton Rouge.

Toward the end of his life, Graham sent a dispatch to an old friend who was now working in the Department of War, William Tecumseh Sherman. He asked Sherman for the government’s permission to use the Pentagon Barracks in Baton Rouge for the school. The irony didn’t escape either man. Years before, when Louisiana decided to oust federal troops from the barracks, Sherman knew he had no other choice but to resign. This time, though, he was happy to oblige.

Mason Graham died in the early morning of Jan. 31st, 1891 at the age of 84. He is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Pineville next to a chapel that had served as the makeshift headquarters for the Union during the Civil War.