Preface

The Saints were robbed, but the state’s budget was saved. The parachute press panicked over a pitiful hurricane, but the Advocate won the Pulitzer for exemplifying the very best about local news reporting. Louisiana lost one of its champions, Kathleen Babineaux Blanco, but not before she received the long overdue gratitude of a state that was enriched by her lifetime of trailblazing leadership and selfless service. Trump came to town, but as for the President, God bless his heart.

Here on the Bayou Brief, we told the true stories of an Erector Set and an Abrascam, but we began the year with an ode to Clementine. When we weren’t covering the election, we shared the tales of a long-lost ship wreck and the forgotten but remarkable lives of the black captains and watermen who built Louisiana back from the ruin of the Civil War. We reintroduced the state to a mayor named Tilly who hoped to bring his city into the catfish farming business and tried to turn a swimming pool into a fishing pond, but ended up leading the bottom-feeders into a massacre.

We traced back the beginning of the Old War Skule to a Union general and a Confederate planter who carried the name of a Founding Father. There were lyrical stories about listening to the river and about a small town named after a saint and ravaged by sinners. And there were stories about the movies and the music that have defined and inspired us.

Before we enter 2020, some hindsight is important. In Part One of this two-part series, we take inventory of the good, the bad, and the ugly of Louisiana politics in 2019.

Le Bon, la Brute, et le Truand de 2019

(The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of 2019)

A few years ago, Bob Mann, the popular LSU political communications professor, biographer, and erstwhile opinion columnist at the Times-Picayune, created his own annual awards, which he would dole out at the end of the year in the pages of the newspaper and on his blog site “Something Like the Truth.” He named the competition after Sergio Leone’s classic spaghetti western “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.”

With his permission, we are reviving this annual tradition with many of the same categories that he created years ago.

Biggest Winner

Gov. John Bel Edwards

In 2015, after he trounced the most powerful Republican in the state, the far-right pilloried John Bel Edwards as the “accidental governor,” serving up a giant dish of revisionist history to console themselves once voters finally had enough of David Vitter.

On the day he took office, Edwards inherited a $2.1 billion budget shortfall and a legislature still under the spell of their most vituperative and mendacious members. Indeed, the very people most responsible for negligently squandering the money that the public had entrusted to their care would spend the entirety of John Bel Edwards’ first term as governor obstinately refusing to help fix what they had broken and repeatedly misrepresenting what was at stake.

While the state’s budgetary woes were the consequence of former Gov. Jindal and this small cadre of the state’s most virulent right-wing partisans, Louisianians could have been spared much of the gridlock and dysfunction four years ago had it not been for a Democratic state representative from New Orleans, Neil Abramson, lining up against the election of a fellow New Orleans Democrat, Walt Leger III, for Speaker of the House. Abramson may have not been the deciding vote, but by turning his back on the newly-elected Democratic governor and his colleague from New Orleans, he nonetheless played a pivotal role in guaranteeing Leger’s defeat and in justifying support for the feckless Taylor Barras. In exchange for his defection, Abramson was given a plum assignment as Chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, a role that proved to be entirely inconsequential in the grand scheme of things. (Incidentally, Abramson’s Wikipedia page was altered to include the laughable claim that his constituents and his district were better-served as a result of his support for Barras. Although those edits have not yet been removed, the user who made them was banned from Wikipedia).

“(Barras) empowered a caucus-led House where party became more important than process,” the Advocate’s Lanny Keller succinctly explained, noting that Barras was also, arguably, the “nicest guy in the state Capitol.” “Politics — above all, not agreeing with Edwards — was even more pernicious in the House. The rules became obstructions to the legislative process.”

Shortly after Barras was elected Speaker, breaking from decades of tradition in which the legislature deferred to the governor for guidance on selecting leadership, House Republican Caucus Chairman Lance Harris touted the importance of an “independent” legislature, but as the past four years definitively proved, Barras’ tenure as Speaker did not usher in a new era of principled independence; instead, the legislature, particularly the House, were dominated by obstructionists.

Nonetheless, despite the inability of some in the House to operate in good faith, Gov. Edwards managed to rack up a remarkable list of accomplishments and resuscitate state government from the disastrous and negligent decisions made during Jindal’s two terms. The $2.1 billion shortfall with which Jindal had saddled the state on his way out is now a $500 million surplus, and as a result of Edwards reversing course and accepting federal funding for Medicaid expansion, nearly 500,000 Louisianians now have health insurance for the first time. Edwards has repeatedly characterized Medicaid expansion as “the easiest big decision” he has ever made in his life.

In a rare bipartisan victory, Edwards and the legislature worked together to usher in a sweeping set of criminal justice reforms that ensured Louisiana was no longer the world’s leader in incarcerating its own citizens.

Although he had preferred to address the state’s budgetary woes by enacting a series of structural tax reforms and avoiding the hike in sales taxes favored by Republicans, his decision to provide local governments more control over who is awarded ITEP (Industrial Tax Exemption Program) incentives helps provide an additional layer of accountability and scrutiny to a program that has proven to be ripe for abuse.

Similarly, Edwards’ support for the ongoing environmental litigation against oil and gas companies who illegally dredged canals and destroyed much of the state’s already-vulnerable coast, in direct violation of the permits they were issued, ensures that the wealthiest industry in the history of human civilization cannot bribe their way out of their responsibility to pay to fix what they broke. The oil and gas and petrochemical companies that dominate the landscape of coastal Louisiana and transformed the corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans from River Road into Cancer Alley have- for far too long- been allowed to operate with impunity, and the residents who live in those communities deserve and demand justice.

As the White House reminded Louisiana voters prior to the bizarre campaign rallies that Donald Trump hosted in support of Eddie Rispone, the state’s economy is performing better than ever. Unemployment is the lowest it’s ever been, and over the course of the past four years, Edwards and his team at LED have landed a series of major economic development “wins,” including a 2,000-job tech facility in New Orleans, the biggest of its kind in the nation.

Although his list of accomplishments is impressive, particularly considering the obstructionism he has faced in the legislature, his decision to affirmatively sign into law the most draconian and punitive abortion law in the country, which sought to prohibit the procedure after five weeks and provided no exceptions in the cases of rape or incest, was rightfully criticized as cruel and brazenly unconstitutional. Indeed, because of a recent decision by the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals that involved a similar but less restrictive law that had recently passed in Mississippi, Louisiana’s law was rendered unenforceable. While it is true that Edwards had made his anti-choice position clear during his first election and that the bill that was sent to his desk had the support of a veto-proof majority in both chambers of the legislature, citizens have a justifiable concern whenever their elected leaders attempt to codify and impose their own religious beliefs on others, especially when they do so with the full knowledge that their actions are in direct violation of well-settled law and nearly 50 years of Supreme Court precedent.

Still, fortunately, most voters recognized the law’s futility, absent a complete reversal by the Supreme Court (which is certainly possible, but probably not plausible, even in the Court’s current composition), and they also recognized that Eddie Rispone represented a far more significant and much more immediate existential threat to healthcare in Louisiana. Among other things, Rispone pledged to enact an enrollment “freeze” for Medicaid applicants, which experts believe would have resulted in more than 300,000 Louisianians losing their health insurance coverage.

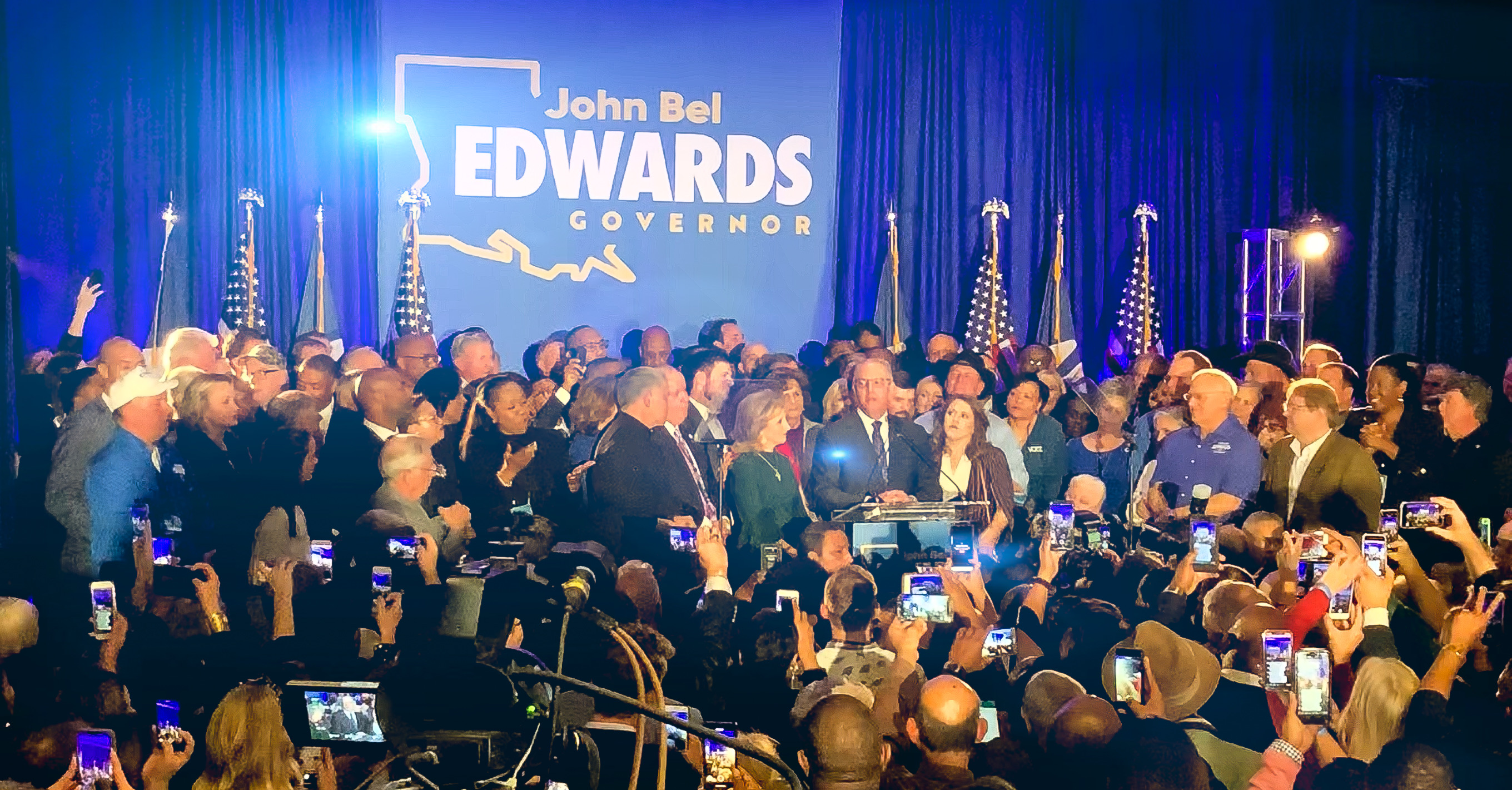

Although it may not make any difference to hard-liners in the legislature, this year, John Bel Edwards proved, once and for all, that his election in 2015 was not an accident. He squared off against two formidable Republican opponents, a well-liked conservative congressman and a wealthy political insider who spent $13.5 million of his own money on a campaign that hinged on ingratiating himself to supporters of the president. Indeed, Edwards didn’t just have to beat Ralph Abraham and Eddie Rispone; he also had to contend the hate machine of the Trump campaign, which invested an enormous amount of political capital in a state he had carried, only three years prior, by nearly twenty points.

In the end, voters rewarded Edwards for his steady, competent leadership and rejected the brand of toxic, vapid, and insult-driven partisanship that swept Donald Trump into a 77,000-vote Electoral College victory over the candidate who had received nearly three million more votes nationwide, Hillary Clinton.

Edwards’ victory proved that his support is much deeper than his opponents had believed and that Donald Trump’s support, even in Louisiana, is far more shallow than they had imagined.

Biggest Loser

Tie: Donald J. Trump and John Neely Kennedy

Since our debut in 2017, we have made a conscientious decision to avoid publishing anything about the 45th President of the United States unless it specifically involves Louisiana. Donald Trump‘s tenure has been characterized by an abandonment of moral leadership and dominated by an erratic, cruel, and profoundly ignorant series of decisions that embolden racists, weaken the rule of law, and undermine the foundational aspirations of this nation of immigrants.

He has appealed to and mimicked the leadership style of authoritarians and despots. He has regularly diminished the dignity of his office (his Twitter account is a never-ending stream of self-aggrandizing baseless braggadocio and unhinged jejune drivel), and although the economy has continued to perform well for some, there is nothing “great” about the America that has been made under his presidency.

But because our focus is on Louisiana, we haven’t had much reason to write about him. Despite the fact that we are led by a Democratic governor, Trump has never been outwardly or singularly antagonistic toward the Bayou State, and during the past three years, somewhat astonishingly, he has enjoyed a cordial working relationship with Gov. Edwards. In fact, John Bel Edwards was the only Democratic elected official invited to the White House for Trump’s very first State Dinner, which honored French President Emanuel Macron. Ironically, the Trump Tax Plan, enacted into law in December of 2017, helped open up an additional source of revenue for the state, triggering a Louisiana law that requires any decrease in federal income tax be offset with a corresponding increase in state income tax (and visa-versa).

That said, whatever marginal benefits Louisiana has gained by having a working relationship with the White House are a credit to our governor’s decency, not to Trump’s leadership, and they pale in comparison to the damage Trump has inflicted on the nation’s most marginalized communities.

That was underscored most prominently during the last month and a half of this year’s campaign season, when the president held three separate rallies in Louisiana to campaign against Edwards. And it was especially obvious in the two rallies he held during the runoff in support of Eddie Rispone, a man whose sycophancy toward the president was so over-the-top it seemed to make even Trump uncomfortable. Indeed, the White House struggled so much to justify his opposition to Edwards that it ended up inadvertently making the case for his re-election, blanketing its social media accounts with talking points about how well the state’s economy has performed during the past three years even though Rispone had been attempting to convince voters exactly the opposite.

In Trump’s final rally in Bossier City, he only stuck to the script once, reading from the teleprompter a series of prepared attack lines against Edwards that were so absurd that Trump, at one point, interrupted himself to let the audience know Edwards had always been good to him in person but others told him the governor “talked bad” about him behind his back. If you were paying close enough attention and recognized that the bluster had been written by a Rispone campaign operative, the subtext was clear: He didn’t believe a damn thing he was saying.

So, why was he even there in the first place?

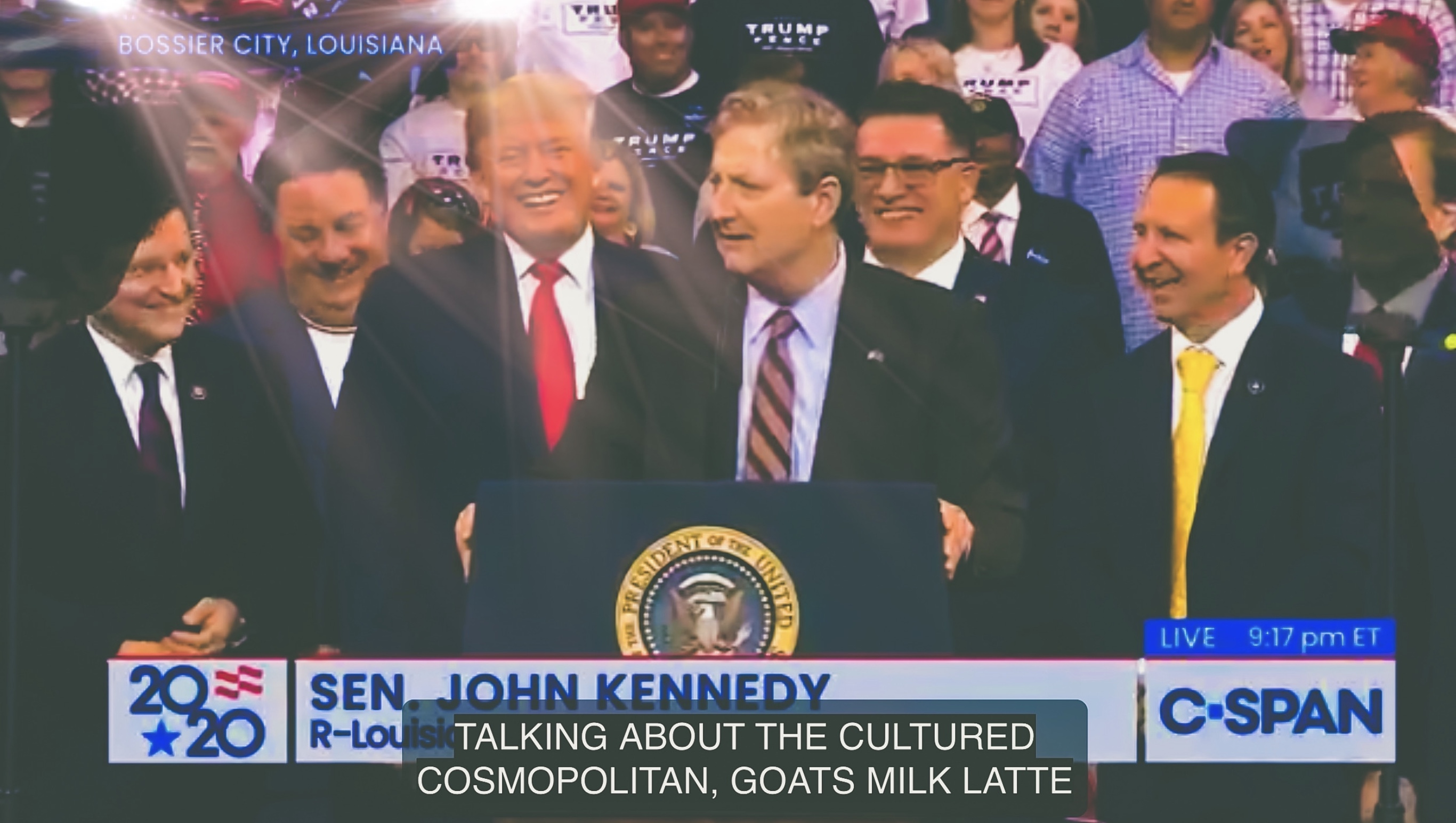

Louisiana’s junior Senator, John Neely Kennedy, is a highly-educated lawyer with degrees from Vanderbilt, the University of Virginia, and Oxford, but since arriving in D.C. in 2017, Kennedy has spent the bulk of his time honing his acting skills. He is the real-world version of Sophie Lennon, the character played by Jane Lynch in the Amazon series “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.” Lennon, a Yale-educated actress, betrays her education and intelligence and becomes famous by performing the role of a gimmicky, frumpy, and crass comedienne from Queens. Everything about the “persona” that made her popular is fake: The accent, the jokes, the fat suit, even the connection to New York.

Kennedy, similarly, has made a name for himself in the Senate by recycling the same formulaic one-liners he used during his audition here as state Treasurer, all delivered with an accent that sounds more like East Texas than South Louisiana. Peter Athas refers to these as “Neelyisms.” The Beltway media has lapped it up, even if, back home, most of us already know the routine. (In fact, most of us remember when our junior Senator was an outspoken Democrat. It wasn’t that long ago). And Kennedy, for his part, has proven himself to be skilled at locating a spotlight and a microphone whenever he can.

It’d be a mistake to confuse his huckster persona with a lack of intelligence, as was made evident during his absolute evisceration of judicial nominee Matthew Petersen. But there is a difference between being an intellectual and being intellectually honest, and as hard as he tries to lampoon liberals as snobbish elites, the truth is that John Neely Kennedy is just as much of a “goats-milk-latte-drinking” elitist as the people he ridicules. Magna cum laude at Vanderbilt. Order of the Coif at UVA Law. First class honors at Oxford’s Magdalen College. He’s the author of an entire casebook on Louisiana Constitutional Law, and, among other things, a law review article titled “The Dimension of Time in the Louisiana Products Liability Act.”

During his eighteen-year stint as Louisiana state Treasurer, he ran for the United States Senate three times. In 2004, as a Democrat, he finished in third in the jungle primary behind fellow Democrat Chris John and Republican David Vitter, who won outright. Four years later, he ran again, this time as a Republican against incumbent Mary Landrieu, and Landrieu very effectively diminished his candidacy by branding his campaign as “Kennedy for Whatever.” She also won outright. But the third time was a charm in 2016, when, in a 24-person field that included two Republican congressmen, two well-funded Democrats, and former KKK grand wizard David Duke, Kennedy squeaked out a 25% first-place finish in the jungle primary and then trounced the second-place finisher, Democratic Public Service Commissioner Foster Campbell, in the runoff.

Initially, he didn’t seem to enjoy his new gig all that much, and almost as soon as he was sworn in, he signaled that he was entertaining a way out. He began testing the waters on a potential run for Louisiana governor, but very quickly, it became obvious that it’d be an uphill battle. Most polls had Edwards ahead of Kennedy in a head-to-head match, and perhaps most importantly, the deep-pocketed donors who had supported his run for Senate weren’t exactly thrilled with the idea of funding yet another Kennedy for Whatever campaign. So, eventually, he made it clear that he had cooled to the idea and would be staying put. However, that didn’t mean he had any intention of staying out. Throughout the campaign season, Kennedy took an unusually active interest in the affairs of state government, trolling Edwards whenever the opportunity presented itself, even if the facts weren’t on his side.

According to the New York Times, at least one member of Louisiana’s federal delegation with knowledge of the president’s decision to involve himself in this year’s gubernatorial campaign (almost certainly not its lone Democratic member, U.S. Rep. Cedric Richmond), Kennedy shoulders much of the blame for convincing Trump to campaign against Edwards, despite the objections of White House political aides. This account matches what others have said on background to the Bayou Brief. Kennedy, allegedly, had misrepresented or cherry-picked polling data and voter surveys to make the case to Trump that Edwards was far more vulnerable than he appeared to be.

The gambit backfired: Even though Trump had essentially gone “all-in,” appearing in those three campaign rallies in Louisiana and dispatching both his son and Vice President Mike Pence, he barely made a dint in turning out voters for Rispone, and whatever positive effect he may have had was offset by the negative. Trump not only couldn’t claim a victory; he had actually helped increase Democratic enthusiasm for Edwards.

Most Competent

State Sen. W. Jay Luneau

Even before this year’s legislative session was gaveled in, the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry (LABI), the trade association that has devolved into a powerful right-wing lobbying organization, had made it clear their top legislative priority was the passage of a bill that claimed to be about reducing the price of auto insurance premiums, something that nearly all Louisianians would enthusiastically support. But there was one small problem: The bill they were promoting, state Rep. Kirk Talbots’s HB 372, the so-called Auto Insurance Premium Reduction Act of 2019, had almost nothing to do with reducing the cost of car insurance and nearly everything to do with protecting the profits of the insurance industry through a series of so-called “tort reforms.”

In recent years, LABI has showered campaign cash on lawmakers with the best grades on its annual “scorecard,” funneling the contributions through one or more of its four political action committees, a questionable arrangement that may implicate the state’s ethics laws, according to two legal experts familiar with the practice. For its part, LABI claims that legislators who support its agenda are not automatically rewarded with financial support; in other words, correlation does not equal causation. But one thing is for certain: Because of its network of ancillary PACs, LABI is capable of single-handedly funding candidates to run against lawmakers who stand in their way. That creates an enormous disincentive for legislators who represent competitive districts to avoid outwardly antagonizing the organization.

Put simply, “tort reform” refers to any changes in the law that minimizes or eliminates a person’s ability to hold a wrongdoer accountable in the civil justice system. Although there is no evidence whatsoever that demonstrates any direct connection between the premiums individuals pay for car insurance in Louisiana and the amount of money the insurance industry as a whole spent on litigation in the state, the business lobby- specifically LABI and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce- have spent a veritable fortune attempting to convince the public that they are the victims of this stubborn little thing known as the law. No doubt, their case has been made easier by a small handful of personal injury attorneys who spend their own fortunes advertising how much money previous clients have received after being injured in a car wreck, often in misleading and sensational terms. (For example, instead of reporting the actual amount that an injured party received, they instead advertise the total damages awarded, conveniently leaving out the massive contingency fees their law firms typically collect).

LABI had, for years, attempted to find a legitimate public policy justification to implement an array of tort reforms, and with car insurance, they believed they finally had something they could sneak through the legislature, provided, of course, that no one asked too many questions about the bill itself.

Perhaps not too surprisingly, Talbot’s HB 372 breezed through the House, but when it arrived in the state Senate, there was one member, in particular, who had read the bill thoroughly and done his homework, state Sen. Jay Luneau, a Democrat from Alexandria. Luneau is a lawyer by trade, but he isn’t the kind who advertises on billboards or day-time court TV shows. He simply wanted to know- mechanically- how Talbot’s bill would work, how it would change existing law, and the answer to a question no one had bothered to ask: What it would cost?

Up until that point, LABI had avoided labeling the bill as a “tort reform” measure, focusing exclusively on the too-good-to-be-true promise of reducing the cost of car insurance. But when Luneau began asking questions, it soon became readily apparent that the bill’s central premise- its primary public policy justification- was a ruse. As it turns out, none of the proposed changes had ever been proven to have any correlation with the price of insurance premiums. No one doubted that Louisiana drivers pay too much; the question was why. The Senate Judiciary A Committee, on which Luneau served as a member, heard testimony from a national insurance expert, Douglas Heller, who outlined a number of sleazy ways the industry inflated prices for customers that had nothing whatsoever to do with a person’s driving record. Separately, the Senate Insurace Committee heard from one of the state’s top insurance lobbyists, Kevin Cunningham, who was ostensibly there in support of the bill but then unwittingly revealed that the proposed legislation was entirely based on a false premise. “I think it’s a misnomer to ever really believe that your (car insurance) rates are ever going to go down,” Cunningham said.

Luneau had offered a separate bill that he then amended to include making a series of regulatory changes outlined by Heller, including ending the practice of discriminating against widows and widowers. That bill failed to make it out of committee.

But most importantly, Jay Luneau was successful at convincing his colleagues on the Judiciary A Committee to request a “fiscal note” from the state Legislative Auditor, in order to get an informed estimate of the financial costs and benefits of the proposed legislation. When the auditor’s office provided the report, it estimated that the savings were entirely speculative and, in any event, likely to be only very minimal at best, but the costs to taxpayers would total in the millions of dollars every year. The legislation would have resulted in a surge in the number of jury trials, inundating an already-overwhelmed civil justice system.

That proved to be the fatal blow for LABI’s “most important bill of the year;” HB 372 died in the Senate Judiciary A Committee.

However, LABI had hoped to have the last laugh against state Sen. Jay Luneau, directly funneling $10,000 to the campaign of his opponent, former one-term state Rep. Randy Wiggins, a State Farm Insurance agent. All told, Wiggins received nearly $27,000 from political action committees, and he personally loaned his campaign another $23,000. The vast majority of his individual donors were fellow insurance agents and brokers; though, altogether, they barely covered his personal loans.

On the night of the jungle primary, Luneau won reelection in a landslide, beating Wiggins 61% – 39% and by more than 6,000 votes.

Already, far-right legislators have signaled their intention to revive LABI’s half-baked auto insurance bill during next year’s session. This time, hopefully, lawmakers will spend more energy working toward an actual solution, instead of reflexively kowtowing to the demands of the insurance lobby. Either way, they should expect at least one state Senator to ask the tough questions.

Most Incompetent

The Campaign to Create St. George, Louisiana

If at first you don’t succeed, lie, lie again.

What had started as an effort to form a new school system turned into a years-long campaign to create a brand-new, affluent, and predominately white municipality in East Baton Rouge Parish. This year, a slight majority of voters in the proposed city approved a ballot initiative enabling the establishment of what could become the fifth largest city in the state of Louisiana, despite its organizers knowing full and well that they were asking voters to saddle those who lived across the street and within the city limits of Baton Rouge with an enormous financial burden. If the courts allow the city’s creation to proceed, then those who will suffer the most are already among the parish’s most vulnerable.

Let’s not waltz around the obvious: The initiative was animated by a series of thinly-veiled racist and classist tropes that have persisted in Louisiana since well before Thomas Jefferson struck a deal with Napoleon Bonaparte, though the notion of using public education as a raison d’etre is from the residue over school integration, something that Louisiana had stubbornly attempted to resist in the decades that followed the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

Baton Rouge was actually the first city in the country in which leaders of the civil right-shirt movement staged a bus boycott, and the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow have continued to perpetuate de-facto segregation and created ample space for two very different versions of law enforcement, as the entire nation was reminded by the harrowing video footage of Alton Sterling’s final moments alive.

Predictably, those who led the fight for St. George insist that the effort has nothing to do with race and everything to do with ensuring “local control,” but the historical truth cannot be altered to account for a contemporary (and convenient) blind spot. Indeed, the taxpayers of Baton Rouge financed the infrastructure upon which the would-be city is built, something that- again- has been conveniently ignored.

But willful ignorance and myopia are not the only reasons we selected the organizers of the campaign to create St. George as the winners of the Most Incompetent Award, because, no doubt, many of those who voted in favor of the new municipality were not motivated by the kind of racial antipathy that had initially informed the proposal. Many were instead led to believe that the new city would be financially self-sustaining and would have almost no negative impact on the region. Moreover, they were also told that the proposal was in compliance with existing law. All of these things are untrue.

Rather than confront the stark reality that their numbers simply did not add up, campaign organizers continually insisted otherwise, even if it meant rejecting the findings of multiple comprehensive analyses and reports. Because so many of the existing retail and commercial developments upon which they had relied to ensure the new city’s financial solvency decided instead to request annexation into Baton Rouge, it’s unclear how exactly St. George would provide for even the most basic services. They may be able to form a breakaway public school district, but they apparently won’t have enough money to fund their own police department.

Additionally, as was clear from the very beginning, the proposal is in direct violation of the approved city-parish plan of government, which expressly prohibits the formation of any new municipalities.

Organizers may have fashioned themselves as patriotic revolutionaries, but there is nothing virtuous or patriotic about capriciously harming your neighbors and misrepresenting the truth about the costs of breaking away.

Most Improved

Col. Rob Maness

In 2017, following two failed bids for the United States Senate, Rob Maness, a retired Air Force colonel from St. Tammany Parish, found himself in the middle of a surprisingly competitive race for state Representative- a seat he should have been able to easily win- when he lost his cool. Maness had decided to openly criticize his fellow Republicans for abandoning Alabama Judge Roy Moore after several women alleged Moore had sexually assaulted them years ago, including two women who claimed the abuse occurred when they were teenagers and Moore was in his thirties.

There was nothing righteous about Manesss’ position. The allegations were credible and lurid, and ultimately, even voters in ruby-red Alabama couldn’t stomach the prospect of being represented by an alleged child molester. But when David Bellinger, a liberal commentator who frequently calls into Jim Engster’s radio show, confronted Maness on air and labeled him an “extremist,” the retired military veteran erupted. “Blow me and get out of here,” he said to Bellinger.

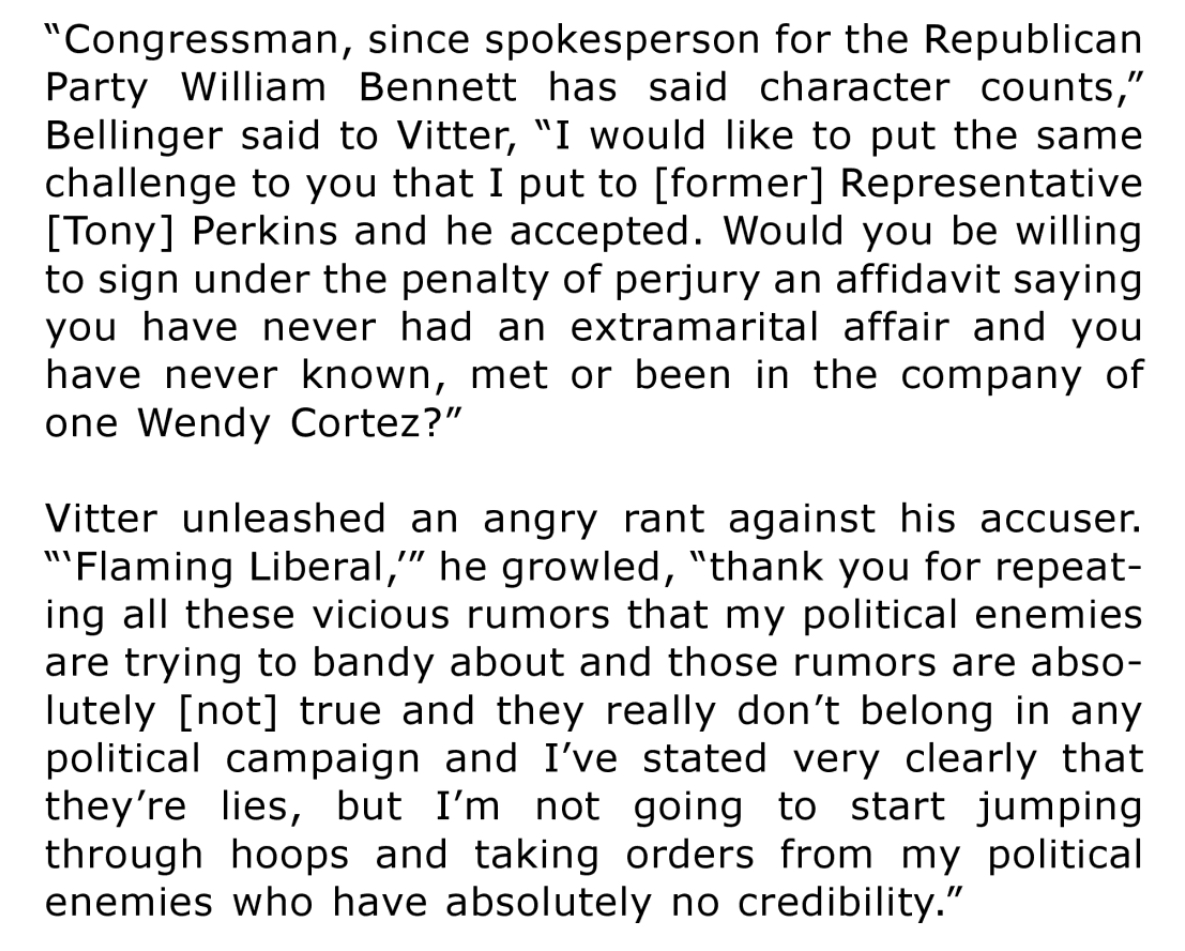

Bellinger, it is worth noting, has made headlines before for crawling under the skin of Republican candidates and elected officials. In the book “Republican Gomorrah: Inside the Movement that Shattered the Party,” writer Max Blumenthal recounts a memorable exchange that Bellinger, who often uses the nom de plume “Flaming Liberal,” had in 2003 with then-Congressman David Vitter:

For Maness, the exchange with Bellinger marked a low point in his public career, and he would go onto lose the race for state Representative to another Republican, Covington City Councilman Mark Wright.

But this year, Maness did something unusual, particularly in the current era of toxic partisanship: He decided to take a principled stance against the very political party he had once reflexively championed, and in speaking about his decision, he shared details about the pain that he and his family had endured as a direct consequence of the actions taken by Louisiana GOP mega-donor and would-be “kingmaker” Lane Grigsby.

Maness decided he’d had enough after Grigsby attempted to bribe a Republican candidate to drop out of a race for the legislature that had appeared to be headed toward a rare three-person runoff and subsequently boasted about the imperial control he had over the state GOP. Two years prior, Grigsby had helped to finance a series of especially nasty attack ads against Maness, and as a result, Maness’ autistic son was abandoned by his only two friends.

Initially, even though he’d announced that he had left the Republican Party and would be “voting for divided government,” Maness couldn’t bring himself to expressly endorsing the Democratic incumbent, John Bel Edwards. But that changed after Eddie Rispone appeared on a morning radio show on Alexandria’s KSYL and told host Jim Leggett that West Point should be ashamed that Gov. Edwards was a graduate.

Maness may not share the same politics as those of us at the Bayou Brief, but his decision to publicly repudiate the endemic corruption and defend the integrity of a leader on the other side of the aisle is commendable and a complete reversal from his cynical defense of Judge Moore only two years prior, which, as David Bellinger accurately pointed out, was “extremist.” It’s unfortunately uncommon for a politician to admit his mistakes and to put principle above party, and it’s especially rare for conservatives in the age of the most mendacious president in American history.

Shameless Ambition

Gary Landrieu

Shortly after Gary Landrieu showed up to qualify as a candidate for governor, he was told by an official with the Louisiana Secretary of State that he wouldn’t be allowed to use the nickname “Go Gary” on the ballot.

Of course, Louisiana has had its fair share of candidates who prefer to be known by a nickname, including former governors Bobby Jindal and Mike Foster, and we’ve had an ample supply of candidates whose nicknames are far less common and much more absurd. Who can forgot Chicken Commander or Live Wire or Cowboy Phil? If they were around today, does anyone doubt that Earl K. Long wouldn’t ask to appear on the ballot as “Uncle Earl” or that his brother Huey wouldn’t be tempted to have “Kingfish” appear next to his name?

The problem with “Go Gary” was that it, very clearly, wasn’t actually his real nickname; it was his campaign slogan. Gary, the first cousin of Mary and Mitch and the nephew of Moon, seems to enjoy capitalizing off of the surname that was made famous in Louisiana by his more accomplished, adult relatives.

This wasn’t his first attempt at elected office. In 2012 and in 2014, he challenged Cedric Richmond for Congress, and in between those two bids, he campaigned for a seat as Councilman-at-large in New Orleans. In 2016, he qualified as a candidate for the U.S. Senate, but by then, it had become obvious that he was more of a professional troll than a serious candidate.

This year, though, he deserves the Shameless Ambition Award not merely because of the ways in which he has acted out his own issues with family jealousy, but because of how he behaved after being told he couldn’t use “Go Gary” as his nickname. Instead of accepting the decision in stride, Gary summoned his elderly mother to the Secretary of State’s office in Baton Rouge to have her repeat the ridiculous lie that “Go Gary” was a nickname that dated back to his childhood. That was shameful of him, and the only convincing part of the whole spectacle was that his disrespect.

The Secretary of State’s office didn’t budge on its decision, and as it turns out, “Go Gary” couldn’t even get his own nickname right. For several days, his campaign Facebook page directed people to the web domain “GoGayGovernor.com.”

Most Authentic

LaToya Cantrell

She was a still a teenager when she arrived in the city she would one day become the first woman ever to lead, an incoming freshman at the one and only Catholic HBCU in the nation, Xavier University, located in the heart of Gert Town. Back in those days, the litmus test question that established a person’s New Orleans bonafides—“Where’d you go to high school?”— carried with it implications about a person’s “pedigree,” their class, their race, their religion, and even their place in the city’s history.

But LaToya Cantrell went to Palmdale High School, nearly 2,000 miles away from the Big Easy, on the other side of the San Gabriel Mountains from Los Angeles. That meant a few things. Yes, she was an outsider, but she was also more free to define herself- on her own terms- than most of her New Orleans-born classmates. The downside, of course, was it’d be difficult- if not impossible- for her to ever be accepted as authentically New Orleanian.

Before Cantrell’s election in 2018, the last person to be elected mayor of New Orleans who wasn’t actually a native of the city was Vic Schiro in 1961. Schiro was born in Chicago, but, unlike Cantrell, he moved to New Orleans with his family when he was still a small child; he could have answered the question about where he went to high school. Before Schiro, there was deLesseps Story “Chep” Morrison, one of the most consequential mayors of the last century. Morrison was born in tiny New Roads, Louisiana, the seat of Pointe Coupee Parish. But through his mother, Mayor Morrison was a descendant of three iconic New Orleans families, the deLesseps, the Storys, and the Tremés. The city’s former red-light district, Storyville, was named after one of his cousins, and his third great-grandfather was Claude Tremé, whose surname also appears prominently on the city map. The point is: For most of its history, despite the fact that it has always been a cosmopolitan city of immigrants, New Orleans has nonetheless been known to be wary of “outsiders.”

LaToya Cantrell didn’t inherit a famous name, and although father-in-law, Magistrate Judge Harry Cantrell, is also an elected official, she didn’t marry into a well-known political family either. Judge Cantrell won his first election in 2013, a year after LaToya Cantrell had won her first, defeating Dana Kaplan for the District B seat on the New Orleans City Council despite being outspent nearly six-to-one. Indeed, her first election would serve as a blueprint for how she approached the race for mayor, relying on an aggressive and relentless field operation that allowed her to build personal relationships with hundreds- if not thousands- of residents all throughout the city.

As a Councilwoman and, before that, as a neighborhood leader, Cantrell made a name for herself as an outspoken advocate for affordable housing and equitable redevelopment. She didn’t get everything right all of the time; her ambivalence about the removal of four white supremacist and Lost Cause monuments, for example, wasn’t exactly a profile in courage. And although she ultimately voted in favor of their removal, the concerns she had expressed about procedural trivialities were unconvincing.

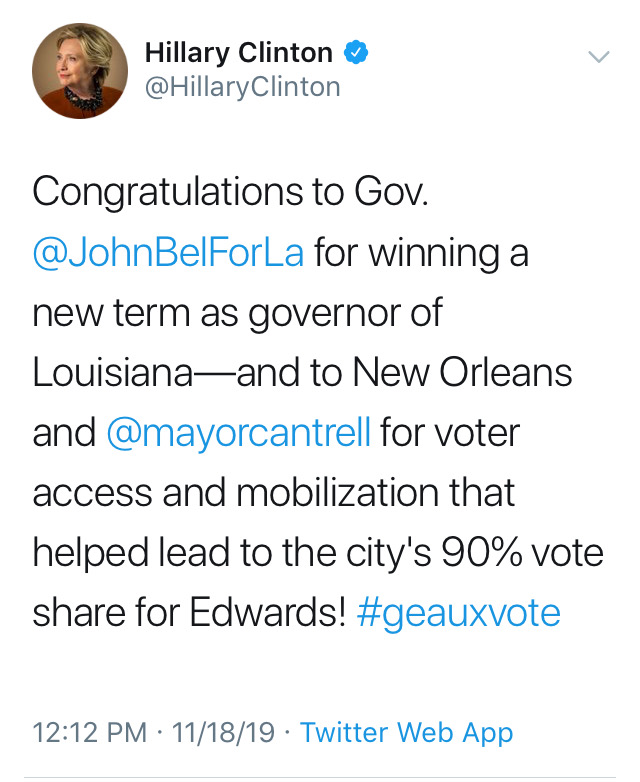

During her year-and-a-half as New Orleans Mayor, however, Cantrell has consistently proven herself to be a born leader, particularly when the stakes are high and the spotlight is on. She has repeatedly stood up against the Trump administration’s egregious and inhumane treatment of undocumented immigrants, and when it looked possible that Eddie Rispone- a man who had denounced New Orleans for being a “sanctuary city” (it’s not) and promised to dispatch Gestapo-like raids in order to arrest and deport those found to be residing in the city without the requisite documentation- could be elected governor, Cantrell turned Action New Orleans, the organization that was born from her campaign operation, into high gear, earning the attention and the admiration of several national Democratic leaders, including Sec. Clinton.

To be sure, there have been slip-ups and mistakes, most notably her decision to quietly approve lowering the speed threshold on traffic cameras located in school zones, which quickly generated more than $1 million in anticipated revenue from tickets sent to unsuspecting drivers. (In April, the Times-Picayune’s James Gill excoriated Cantrell for “hornswoggling” New Orleans voters over the traffic camera issue). As a result of the public backlash against the way in which the new policy had been rolled out, the city decided to refund drivers who were ticketed before the changes were announced. Others have criticized the Cantrell administration for its lackadaisical approach toward enacting or enforcing a coherent set of regulations that could stem the unfettered proliferation of short-term rentals, which have already priced many people out of the city’s increasingly expensive housing market.

But when faced with the biggest and most important test that she has encountered thus far- the looming threat of a potential hurricane aiming its sights on the Louisiana coast, LaToya Cantrell was at her absolute best, looking less like a rookie mayor and more like a seasoned veteran who knew how to speak with authority and calm the nerves of a city that the national media had shamelessly attempted to stir into a panicked frenzy. Without question, her steady, even-keeled approach, along with the city’s near-perfect deployment of its emergency preparedness protocols, prevented the kind of nightmare scenario similar to the one that unfolded in Houston in 2005, when more than 100 people died in the process of evacuating in advance of Hurricane Rita. Rita pummeled the Lake Charles area, but Houston was spared completely.

Cantrell deserves immense credit for refusing to contribute to the sensational and entirely baseless doom-and-gloom that was being sold by the national media; at one point, her team even called out the Washington Post directly for its irresponsible coverage.

And since this is about her authenticity, it’s also worth mentioning that her enthusiasm for the Saints isn’t something you can fake.

In a state dominated by the far-right and represented in Washington by seven white Republicans, all of whom have tethered themselves to a president that, with only one exception (Clay Higgins), they had privately opposed as a candidate, and only one African American Democrat, LaToya Cantrell offers a refreshing reminder that, in Louisiana, our very best leaders have always known how to inspire people by simply being honest with themselves.

Biggest Blunder

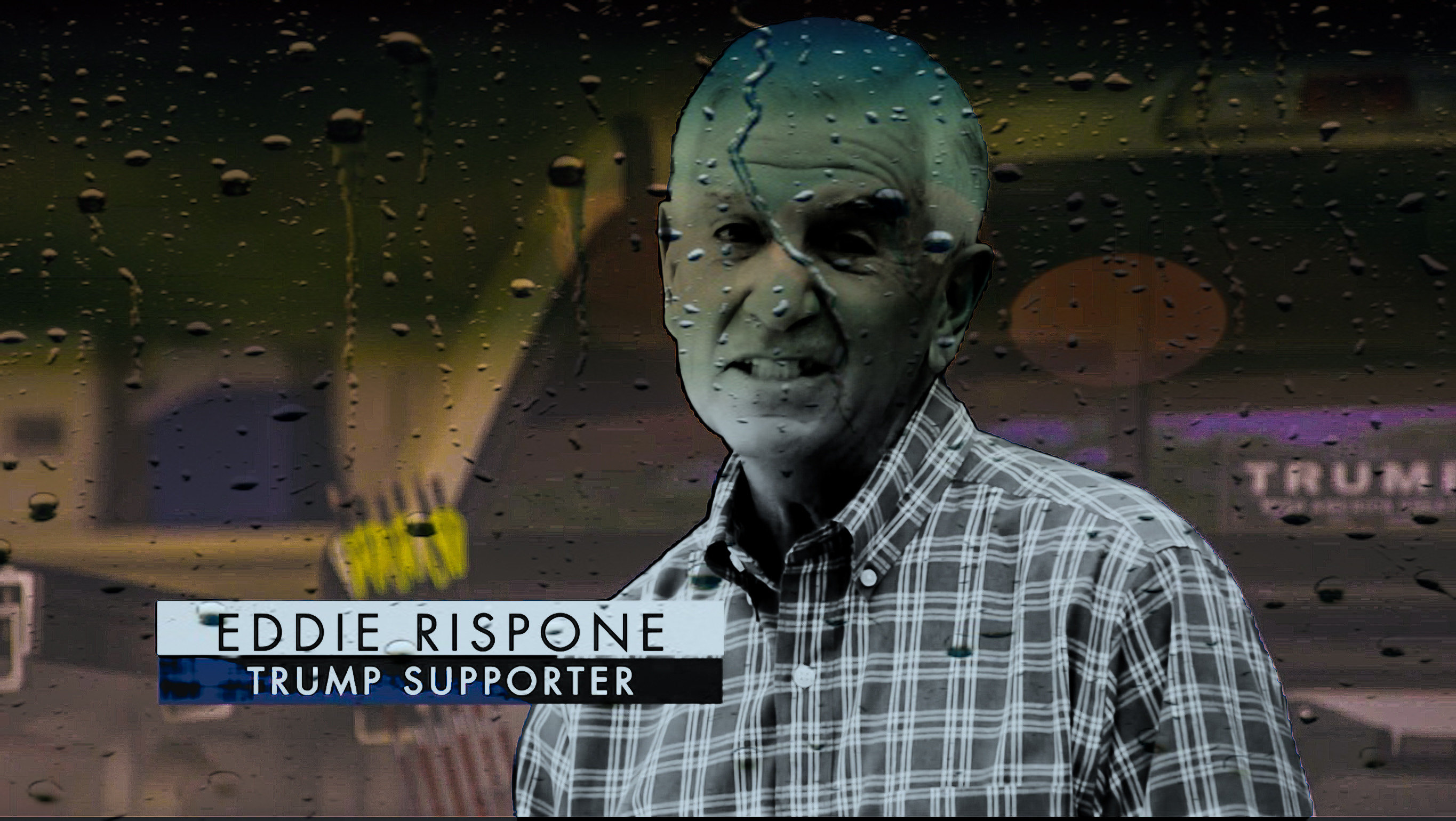

Eddie Rispone’s First Commercial

This year, Eddie Rispone accomplished something extraordinarily rare in American politics: He somehow managed to lose support from the commercial that introduced him as a candidate for governor. It’s difficult to overstate how disastrous his debut was. Over the next five months, he would end up spending $13.5 million of his own money attempting to repair the damage. It’s important to note that, prior to declaring his candidacy, Rispone had been almost completely unknown.

Even today, with the benefit of hindsight, he still seems to believe that the problem with the commercial was the pitch of his voice and not the pitch he was selling, cluelessly claiming to the Advocate that the team he had hired didn’t realize he normally didn’t sound as nasally (notwithstanding the fact that, presumably, he still approved and paid for the ad to blanket the airwaves).

No, the most glaring problem with the ad had nothing to do with his Ross Perot impression; the problem was its basic premise: It wasn’t about Eddie Rispone, the self-made millionaire with a vision for how to lead Louisiana (perhaps because he didn’t really have much of a vision other than changing a few things that would financially benefit his business). The commercial was about Eddie Rispone: Trump Supporter, and right out of the gate, Eddie Rispone: Trump Supporter made himself immediately unlikable to nearly half of the state’s electorate and antagonized the entire city of New Orleans.

Trump may remain slightly above water in Louisiana, with 53% of voters approving of his job performance, but according to Morning Consult, since taking office, Donald Trump’s net approval in the state has decreased by 21 points. By putting Trump, who wasn’t even on the ballot, front and center, literally towering over Rispone and his wife, Rispone had effectively introduced himself not as a leader but as a follower.

But the decision to frame his introductory commercial around his obsequious support of the president isn’t the only reason the ad was such a spectacular failure. Rispone outlined three things he would do if elected governor: Work with the president on protecting Constitutional rights (i.e. the Second Amendment, not the First or the Fourteenth Amendments); ban sanctuary cities (and to ensure everyone understood he was talking about New Orleans, he included aerial footage of the French Quarter), and end taxpayer benefits for illegal immigrants (a nonsensical and vague pledge he would make repeatedly and that apparently referred to an estimate that 0.05% of Medicaid spending went toward physicians and hospitals for treating undocumented patients).

Put another way, Rispone’s message was Trump, guns, and illegal immigration, all issues that may have poll-tested well with conservative voters but have almost nothing to do with the job responsibilities of the governor.

But the line that was most memorable- and that ended up defining Rispone for the rest of the election was his reference to the Trump bumper sticker he put on his pick-up truck. He may have been telling the truth, but because of the way the commercial was staged, it came across as frivolous and scripted. Soon thereafter, GumboPAC responded with an ad that would end up defining him for the rest of the election season and would be replicated later by John Bel Edwards’ campaign: A still-frame image from Rispone’s debut commercial of the Republican candidate sitting on the flatbed of his truck, with his Trump bumper sticker visible on the back windshield, along with a caption that succinctly expressed what most people were thinking: Phony Rispone.

Most Innovative Idea

Douglas Heller

During the discussion that occurred in the state Capitol this year over how to best address the state’s high price of auto insurance, most lawmakers (and even a few members of the media) seemed more than happy to accept at face value the specious arguments made by the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry (LABI). As we mentioned earlier, the right-wing business lobbying organization was nearly successful in ramming through a series of changes to existing law that purported to be designed to lower car insurance premiums but actually amounted to a costly giveaway to the insurance industry, all intended to rig the civil justice system against drivers and in favor of insurance companies.

It’s always a good idea to be skeptical whenever politicians begin preaching about “tort reform,” because most of the time, the real aim is to make it more difficult for ordinary Americans to hold the powerful accountable.

There is no question that car insurance is too expensive in Louisiana. Depending on who you ask, we pay either the second or fourth highest prices in the nation on insurance premiums. However, there is significant disagreement about what is driving up those costs. The insurance industry blames trial lawyers, suggesting that people like Gordon McKernan and Morris Bart- whose billboards and commercials are ubiquitous across the state- are the symptom of a legal climate that makes it vastly more expensive to do business. They latch onto isolated and often inaccurate stories about frivolous lawsuits and staged car wrecks to illustrate their point, and in so doing, they’ve been able to convince a great number of otherwise reasonable people that the insurance companies are the real victims, not the people who seek remedy through the justice system.

It should be obvious, but considering the way in which the debate has been framed in Louisiana, it bears emphasis: If you’re in a dispute with an insurance company, you’re inherently at a disadvantage. They hold nearly all of the cards. It also should be noted: Despite their pollyannish outrage over lawyers who advertise their services, the insurance industry spends more every year on advertising than almost anyone else in the state of Louisiana, easily five times the amount the legal industry spends.

This year, the Bayou Brief teamed up with Douglas Heller, a nationally-renowned expert on auto insurance and how public policy affects the industry’s profits and the premiums they charge drivers. Heller spent nearly three months studying Louisiana’s auto insurance market and the laws and regulations that govern it, and his findings, which he presented on two separate occasions to the legislature, suggest there are several ways the state could act to lower the costs of car insurance premiums. Unlike the proposal pushed by LABI, the solutions outlined by Heller have all been empirically proven to work.

Despite their claims to the contrary, the truth is that the insurance industry continually hits their profit targets in Louisiana, year after year. They’re not hurting, far from it, in fact. Indeed, the proposal that LABI outlined, which was carried by state Rep. Kirk Talbot’s HB 372, would’ve resulted in only one thing for certain: Millions more in taxpayer spending every year.

Heller’s “innovative idea” is actually quite simple: Enforce existing regulations that are designed to protect consumers and enact laws that prohibit insurance companies from discriminating against drivers on the basis of their credit score and gender and prevent companies from penalizing widows, widowers, and those reentering the marketplace, like returning military veterans.

If the legislature is seriously concerned about lowering premiums and not lining the pockets and rigging the system in favor of the insurance industry, then the conversation should begin with insurance- and not tort- reform.

Most Embarrassing Quote

Lane Grigsby

Alexandria native Lane Grigsby made his fortune and a name for himself 125 miles away from his childhood home on Thornton Court, arriving in Baton Rouge for good after his new bride and their new baby made it impossible for him to remain at West Point. Aside from a profile in the Town Talk several years ago, Grigsby had been largely forgotten in Alexandria. His construction company, Cajun Industries, didn’t do much work in Central Louisiana, and even though he emerged as a prominent Republican megadonor more than two decades ago, he largely stayed out of the area’s politics as well.

This year, however, Lane Grigsby became known across the state, and in the city of his birth, he finally made a name for himself, not as Boo’s son or as the hometown boy who struck it rich, but as a smug, conniving, and brazenly unethical partisan radical who attempted to bribe, lie, and buy his way to the top of state government, not as a kingfish but as a kingmaker.

Four years ago, recognizing before many others in the Louisiana GOP that David Vitter’s gubernatorial campaign was doomed, Grigsby asked for and received a refund of the $100,000 donation he’d made to Vitter’s PAC, and along with his close friend and fellow construction magnate Eddie Rispone, he poured a fortune into electing a slate of like-minded candidates to the state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE). No one had ever before spent as much on BESE elections, and with the state’s attention squarely focused on the top of the ticket, nearly all of the candidates supported by Grigsby and Rispone won their races. They had effectively ensured that they would both possess disproportionate influence over state education policy- or, at the very least, the ability to force a stalemate over changing education policy. Both Grigsby and Rispone were outspoken supporters of school privatization initiatives and funneling taxpayer dollars to vocational training tailor-made to fit the workforce needs of their construction companies.

A couple of years later, the two men decided to embark on another electoral project: They began actively attempting to recruit a candidate willing to run against incumbent Gov. John Bel Edwards. This, as it turned out, was easier said than done. No one of their shortlist was interested in the gig. Steve Scalise, their top choice, was adamant about staying put in Congress, where he currently serves as House Minority Whip. And the interview they had with U.S. Rep. Ralph Abraham had left them unimpressed; afterward, Grigsby couldn’t even remember Abraham’s name, referring to him as Abramson. That’s around the time that a sleep-deprived Rispone decided that God Himself wanted him to run for governor;

Eddie Rispone would spend millions of his own fortune directly on the campaign, and his friend Lane Grigsby would spend his millions through a shadowy constellation of PACs and nonprofits he’d created to support Rispone through negative advertising against Edwards.

Grigsby’s primary beneficiary was a 501(c)(4) he founded called, ironically, Truth in Politics. Truth in Politics had intermittently published a website that was designed to resemble a news organization, but their real debut was a commercial that aired stateside that featured Juanita Bates-Washington, a former aide to gubernatorial assistant Johnny Anderson. In the commercial, Washington, who goes by several different aliases and had collected hundreds of thousands of dollars in tax liens and a string of disgruntled former colleagues, inaccurately implied that she was fired from her job by the governor after credibly accusing Anderson of sexual harassment. Notably, Washington’s attorney, Jill Craft, who negotiated a settlement on her behalf, subsequently issued a public endorsement of John Bel Edwards, and after making a splash with the commercial, a public records lawsuit, and a press conference during the jungle primary, Truth in Politics lost interest in Washington in the runoff campaign. Their next ad, which inaccurately claimed that one of Edwards’ college classmates had been given a lucrative, multi-million dollar state contract, was ordered to be taken off the air.

But Grigsby’s award-winning quote- “I’m a kingmaker. I talk from the throne.”- actually had nothing to do with the governor’s race, at least directly. When it looked as if there could be a rare three-way runoff election for a state Senate seat in Baton Rouge, which included two Republican candidates and one Democrat, Grigsby attempted to convince one of the two Republican candidates to drop out in exchange for a promise of future financial support. When Grigsby’s offer made headlines, it was met with bipartisan outrage. And in a moment of candor, Grigsby lashed out, proving himself to be even more of megalomaniac than he appeared and reinforcing the belief among many that Eddie Rispone, if elected governor, would merely be a proxy for his buddy, the self-anointed kingmaker.

(Dis)Honorable Mention for Most Embarrassing Statement: “I am a person of myself.” – Eddie Rispone.

Biggest Liar

Jeff Landry

It took nearly two weeks before General Landry, as he calls himself, realized that the campaign commercial he had been airing statewide contained one glaring error: The word Louisiana was misspelled.

It’s a fitting metaphor for how he had led the state Department of Justice during the past four years. Landry has certainly provided us with plenty of material: His creation of a phony police force to arrest people in the French Quarter for smoking pot, the official-looking badges he handed out to his friends and campaign donors, his apparent contravention of state policy on travel reimbursements, his clearly politicized and ultimately fruitless investigation into LaToya Cantrell’s city credit card, and his use of federal HUD fair housing funds to purchase thousands of pens and plastic go-cups with his name on them, among other things.

But the reason Landry deserves this year’s Biggest Liar Award is because of another glaring inaccuracy that appears in his campaign commercial. To be sure, it’s something said about him, not something said by him directly, though that’s a distinction without much of a difference given that it was still his commercial.

Last year, Jeff Landry joined Ken Paxton, the disgraced Texas attorney general who is still awaiting trial after being indicted in 2015 with two securities fraud felonies, in a suit over the constitutionality of Obamacare’s individual mandate. The U.S. Supreme Court, in a majority opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts, had previously ruled that the individual mandate was constitutional under the Tax and Spending Clause, even though most legal scholars had believed the more compelling constitutional rationale was located in the Commerce Clause. Eventually, a Republican-led Congress effectively eliminated the penalties imposed against people who do not comply with the law’s individual mandate, which provided Landry, Paxton, and other far-right Republican attorneys general to challenge the law again. The central premise of their argument is that because the penalty has been reduced to nothing, the individual mandate should no longer be considered constitutional under the Tax and Spending Clause.

Hoping for a favorable ruling, Landry and Paxton filed the suit in the Northern District of Texas (it’s a tactic known as forum-shopping), and as predicted, the judge agreed, sending the case to the conservative Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal. Recently, a divided, three judge panel in the Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court’s ruling but sent the case back to Texas for a clarification on whether or not the individual mandate is severable (or removable) from the Affordable Care Act or if the entire law should be held unconstitutional.

It’s important to emphasize: Landry’s objective isn’t just to have an unenforced penalty be declared unconstitutional. He hopes to convince the court to throw out the entire Affordable Care Act, and importantly, that’d also mean ending legal protections for people with pre-existing conditions.

Landry didn’t bother to worry himself or the legislature about how to ensure Louisiana kept the widely popular provisions that guarantee insurance companies cannot discriminate against people with pre-existing conditions. That means if Jeff Landry is ultimately successful, his efforts could be devastating for hundreds of thousands of people in Louisiana.

So, what did Landry’s commercial claim? Why did he think he deserved to be reelected?

According to a teenager named Bella, who suffers from cystic fibrosis, and her mother, apparently, Jeff Landry somehow guaranteed protections for people with pre-existing conditions, the precise opposite of what his lawsuit intends to do.