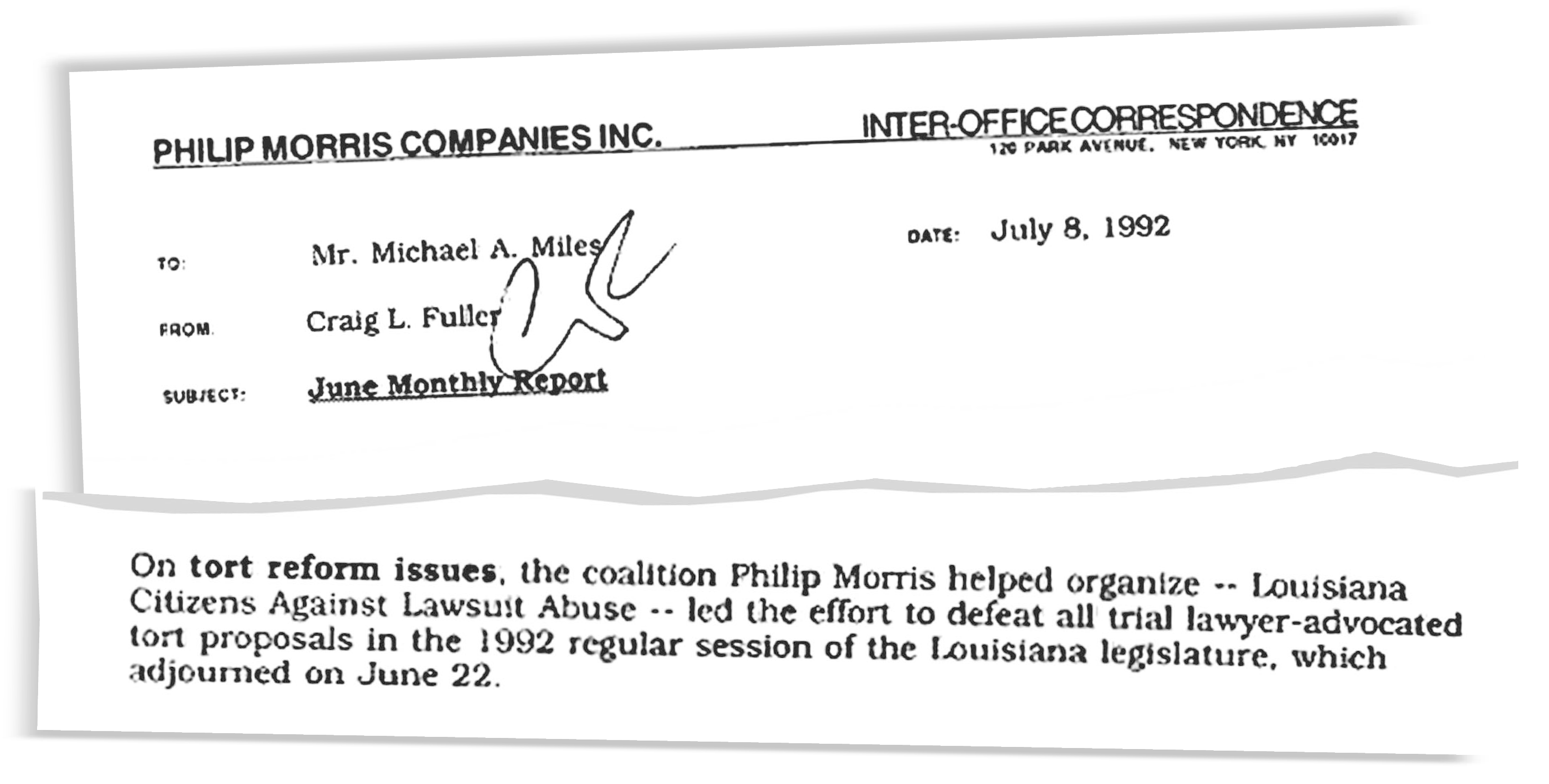

Nearly 30 years ago, a constellation of paid lobbyists, corporate front groups, phony think tanks, and Louisiana’s most powerful trade association mounted a massive, aggressive campaign for “tort reform,” pressuring legislators to reject a package of civil justice expansions and prevent the repeal of a products liability law.

Unbeknownst to the public, however, the effort was created and almost exclusively funded by cigarette manufacturers. Today’s push for “tort reform” was built on the same foundation and constructed around the same scaffolding left in place by Big Tobacco.

Prologue:

“It’s déjà vu all over again.” – Yogi Berra.

Almost everyone over a certain age remembers the case of the New Mexico grandmother, Stella Liebeck, who was awarded $2.86 million after spilling a cup of McDonald’s hot coffee on her lap. It made headlines all across the globe, and since then, it’s been the punchline of countless, mostly bad jokes, including a reference in the most recent Will Farrell and Julia Louis-Dreyfus comedy, “Downhill,” when a French ski resort official indignantly proclaims, “This isn’t America, where you sue when your coffee is hot.”

Most, however, don’t recall that, prior to the suit, McDonald’s had been requiring their restaurants to serve coffee at 180 to 190 degrees, a temperature it knew to be at least 20 degrees higher than what was safe, and most are not aware that Liebeck, who acknowledged it was her fault for spilling the coffee and who had repeatedly attempted to settle the case for $20,000, had suffered third-degree burns, so severe she required skin grafts and was permanently disfigured.

The media largely overlooked the fact that the jury award (which was later reduced) amounted to the profit McDonald’s made in only two days from its coffee sales, and news coverage rarely mentioned that the company had known about more than 700 other customers who had also been badly injured. Liebeck subsequently settled for around $600,000, and McDonald’s agreed to stop burning their customers and changed the way they served coffee.

The jury had meant to send a message to McDonald’s to get their act together; that’s part of the point of punitive damages: A jury of ordinary citizens making it clear that their community isn’t okay with a restaurant maiming grandmothers.

But instead, the case became used as the prime example of “jackpot justice.” It was endlessly cited by proponents of “tort reform,” which they said was needed to end the proliferation of what they called “lawsuit abuse.”

At the same time of the McDonald’s case, “large corporations afraid of being sued for making unsafe products created front groups like Citizens Against Lawsuit Abuse to turn public opinion against lawsuits,” University of Washington professor Michael McCann explained to Adam Conover of Adam Ruins Everything. “(But) the best social science evidence shows that the number of personal injury lawsuits in recent decades has declined, and the median payout is only $55,000.”

Right now, Louisiana’s most influential business lobbyists are peddling a story that seeks to blame frivolous lawsuits for all of the state’s economic woes, and a paid network of incurious and reflexively conservative apologists have attempted their best to reinforce this narrative.

Despite what these groups and their allies in the legislature proclaim publicly, the push for “tort reform” in Louisiana has never remotely resembled a grassroots campaign; rather, it has always been a narrative constructed and scripted by big corporations. For the past two years and under the pretense of protecting consumers, “business-friendly” conservatives in the state legislature have attempted to use the problem of expensive car insurance to justify the passage of a series of laws that would force innocent victims to spend exponentially more money to access the civil justice system.

If this all sounds familiar, it should.

I. How Louisiana Became the Epicenter in the Battle Against Big Tobacco

“It ain’t the heat; it’s the humility.” -Yogi Berra

New Orleans resident Frank J. Lartigue was just nine years old when he started smoking cigarettes. He preferred Picayune Extra Milds, the “Pride of New Orleans.” This, of course, was a long time ago, in 1899 to be exact. Murphy J. Foster, Sr. was in his final year as Louisiana governor; a century later, his grandson would hold the same office.

For the next 55 years of Frank’s life, he smoked at least two packs a day, eventually switching his Picayunes for Camels. But at some point, his breathing became more labored. He knew the cause, and so did his wife Victoria. It had to be the cigarettes.

As we now know, the tobacco companies knew this as well, but at the time, they were concealing studies from the public; in fact, they continued to promote cigarettes as beneficial for your health in magazines, newspapers, billboards, and even television commercials.

After his death, his widow sued the cigarette manufacturers, and she hired one of the nation’s best lawyers, Melvin Belli of San Francisco, later known as “the King of Torts,” to represent her.

In 1958, the Louisiana case Lartigue v. R.J. Reynolds became the first tobacco lawsuit in the nation to make it to the jury. The jury wasn’t buying it, however. The King of Torts would fly home to California and establish himself as a legal giant, and cigarette manufacturers would continue to evade responsibility, mislead the American people, and conceal the truth about their industry.

More than three decades later, at the age of 87, Belli returned to Louisiana at the urging of New Orleans attorney Wendell Gauthier for the chance to take another shot at Big Tobacco.

“30 years ago I filed the first suit against these same tobacco companies in the same city of New Orleans. We lost because we couldn’t prove the addiction of nicotine then,” Belli said at the time. “Now I have great satisfaction in filing this first class action suit with Wendell Gauthier against this industry that will finally have to defend themselves against these charges. We will prove that the tobacco industry has conspired to catch you, hold you and kill you, all without a moment of remorse or self-examination.”

Originally, that lawsuit, Castano v. American Tobacco (1995), seemed likely to become the largest class action case in American history, but on appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit decertified the class, forcing the team of more than 60 law firms that Gauthier had assembled to adopt a new strategy. The Castano lawyers, each of whom pitched in $100,000 to participate, filed more than two dozen suits, “baby Castanos,” in state courts, though only one of which, Louisiana’s Scott v. American Tobacco, eventually made its way to trial.

In Scott, the court later required Big Tobacco to pony up nearly $300 million (originally $591 million) to fund a smoking cessation program for those in Louisiana who had picked up the habit before 1998. (In November of 1998, Big Tobacco agreed to pay 46 states, including Louisiana, $206 billion in damages, a landmark victory also known as the Master Settlement Agreement). As of last year, more than 100,000 people had qualified as members of the Louisiana Smoking Cessation Trust.

But I’m getting ahead of myself, because all of these years later, it is easy to forget that, at the time, cigarette manufacturers were still telling the entire world that while their products may have been harmful to your health, they most certainly were not addictive. The companies endured over 40 years of lawsuits and had never paid a dime in damages.

However, by the early 1990s, their story began unraveling.

II. Castano

“You’ve got to be very careful if you don’t know where you are going, because you might not get there.” – Yogi Berra

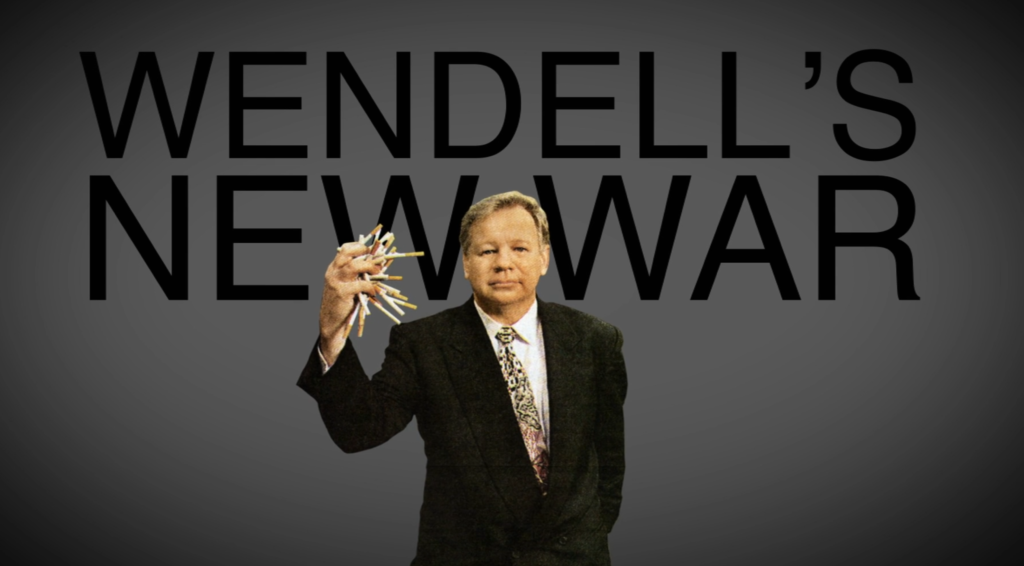

Wendell Gauthier considered Peter Castano to be his “absolute best friend.”

“You know, your relatives, your born with. Your friends you select,” Gauthier told the Los Angeles Times.

He spoke with the kind of lilting drawl that pegged him, at least to other Louisianians, as someone who grew up hours away from New Orleans, in the prairies of Cajun Country. It was the same cadence as the state’s governor, Edwin Washington Edwards, who had started his career as a lawyer in Crowley in Acadia Parish, 11 miles down the road from Gauthier’s boyhood home in Iota. Not surprisingly, the two men were friends; Gauthier’s father had managed Edwards’ very first campaign, a run for Crowley City Council.

The brash and garrulous Gauthier had already slayed a few dragons before he battled Big Tobacco, and as a result, his boutique firm in Metairie had suddenly become known as “elite.” He drove a Rolls Royce, bought an ownership stake in the New Orleans Saints, and lived large. In 1993, Gauthier lost his best friend to lung cancer, and at the urging of Peter Castano’s widow, he decided to take the fight to Big Tobacco.

His approach, however, was different. While others had tried and failed to hold the companies accountable for smoking-related illnesses and deaths, he focused on consumer fraud, and as it turns out, his timing couldn’t have been better.

Secretly, Phillip Morris had hired a behavioral pharmacologist, Dr. Victor DeNoble, to help them develop a “safe cigarette.” The company knew nicotine caused cancer and heart problems, despite what they’d been saying in public, and they needed DeNoble to find out if there was anything they could use to replace nicotine. It would have to be addictive, which was necessary to ensure repeat customers, but it couldn’t be bad for your health.

DeNoble began running experiments with laboratory rats, and fairly quickly, he was able to demonstrate, definitively, that cigarettes weren’t just addictive and bad for your health because of the nicotine. There were other dangerous chemical additives as well. It’d be impossible to ever develop a “safe cigarette.” DeNoble’s research had been a breakthrough, and he rushed to publish a paper in a scientific journal.

Phillip Morris executives, on the other hand, did everything they could to sweep it under the rug. They stopped DeNoble from publishing his research, closed down his lab, reminded him of his nondisclosure agreement, and then, they fired him.

But they couldn’t contain the research forever.

When U.S. Rep. Henry Waxman announced his intention to call the executives of the seven largest tobacco companies before the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health and the Environment, he heard rumors about DeNoble’s research. And when the opportunity presented itself, he coordinated with one of his colleagues to ask the President of Phillip Morris, on the spot and under oath, to release DeNoble from any confidentiality agreement.

Down in Louisiana, Wendell Gauthier was watching on television.

He’d been corralling other plaintiffs lawyers to work with him on his class action suit against Big Tobacco, which had planted its political apparatus in the state only a year before and was spending a fortune riling up voters about “personal responsibility” and “lawsuit abuse.”

Louisiana’s chapter of Citizens Against Lawsuit Abuse wasn’t just funded by Big Tobacco; it was essentially created by Big Tobacco, which hired a former state legislator to be its spokesperson.

When DeNoble finished testifying in front of Congress, there was a message waiting for him on his answering machine.

“Doc, my name is Wendell Gauthier, and I’m the best goddamn lawyer that you’ll ever see,” the man said. “I’m watching you on television, and dammit, you’re good. Me and you, we takin’ the sons of bitches down.”

DeNoble called him back. He was on board.

“Wendell decided it was time to sue the tobacco companies,” New Orleans plaintiff attorney Joseph Bruno later recalled in the documentary Addiction, Inc. “At the time, I thought, ‘You’re out of your freaking mind. You know, they’ve never lost a case. It’s impossible.'”

III. Team-building

“Pair up in threes.” – Yogi Berra

Today, it is impossible to separate the well-funded campaign for “tort reform” and the proposals in the Louisiana legislature to change state law, under the pretense of lowering auto insurance premiums, with the legacy of Big Tobacco.

Indeed, some of the very organizations at the center of the effort are the offspring of tobacco companies and the now-defunct Tobacco Institute, which were exposed as participants in what Judge Gladys Kessler of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia found to be “a massive 50-year scheme to defraud the public, including consumers of cigarettes, in violation of RICO.” And other organizations, particularly the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry (LABI), had been the beneficiary of Big Tobacco’s public relations operation.

As lawmakers debate the merits of a proposal to limit a victim’s rights in the civil justice system, the champions of “tort reform” are employing the same tactics and using an almost identical set of talking points that Big Tobacco developed during the 1990s: bogus studies and phony or exaggerated outrage amplified and recycled by a small network of paid lobbyists and industry front groups who all cynically pretend to be representing a grassroots movement.

During the 1990s, while plaintiffs attorneys battled in the Louisiana legislature and against an adversarial governor, they found more success where it mattered: the courtroom. The hysteria over “jackpot justice” and “lawsuit abuse” worked primarily as soundbites. When people learned the full story, they were far more likely to support the victims and far less sympathetic to the notion that big corporations should be allowed to evade responsibility whenever it was bad for their bottom line.

If you’re interested in learning more about the history, the Center for Justice & Democracy and Public Citizen published “The CALA Report: The Secret Campaign by Big Tobacco and Other Major Industries to Take Away Your Rights” nearly 20 years ago, and you can read the full report in the Coda at the very bottom.

IV. Coda

“It ain’t over til it’s over.” – Yogi Berra

Wrecked: A “Premium Reduction” Bill That Would Only Reduce Car Insurance Accountability, Protections for Injured

On Monday, the state House Civil Law committee recommended a bill that, if signed into…

Wrecked: How Auto Insurance Takes Louisiana for a Ride

Louisiana’s auto insurance rates rank as one of the most expensive in the nation, right…

In Louisiana, Widows Pay As Much As 15% More for Auto Insurance

Four of Louisiana’s six largest auto insurance companies increase rates for people who have lost…

In Louisiana, Auto Insurers Charge Wealthy Drivers with a DWI Staggeringly Less Than Drivers with a Spotless Record but Poor Credit.

Most drivers do not realize that their credit history might be the cause of their…

In Louisiana, Auto Insurers Have a License to Discriminate

Driven Into the Ground

This afternoon, following a nearly four hour-long debate, Louisiana state Rep. Kirk Talbot’s sweeping tort…

VIDEO: Douglas Heller, Nationally-Acclaimed Auto Insurance Expert, Eviscerates LABI-Backed “Reform” Bill

The Task Farce: What a Missing Report Reveals About the Insurance Industry’s Failed Effort to Avoid Accountability

On April 15th, when state Rep. Kirk Talbot first introduced HB 372, a now-defeated proposal…

Major Insurers Charge Louisiana’s Blue-Collar Workers More for Basic Coverage Than White-Collar Workers

Insurance Commissioner Donelon Accepts $20K from Man Indicted for Attempting to Bribe NC Commissioner

Deployment Penalty: How Big Auto Insurers Hike Premiums on Returning Vets

In what amounts to a deployment penalty, several large Louisiana car insurers raise rates, in some…

Careless Operation: Part One