I’ve done my part, in all the things.

More than 40 years ago, I served my country, in the Army.

After that, I married, had and raised three kids who now have their own families. Don and I stayed together through richer, poorer, in sickness and in health until his death parted us last year.

I’ve worked at whatever jobs were necessary to support my household: as a nursing assistant, making beds and emptying bedpans; tending bar, waiting tables or painting houses; as a bill collector or tax preparer.

And for the past 25 years, I’ve brought you the news – in one form or another. I’ve done radio newscasts, sportscasts, weathercasts, and voiced your weekend lineup of community events. I researched, shot, wrote, and presented TV stories on education issues for LPB. After that, I updated you five days a week on Louisiana political issues via the state’s various NPR-affiliate stations. And for the past couple of years, I’ve been bringing you in-depth coverage of the state Legislature, along with environmental issues through the long-form journalism we do here at the Bayou Brief.

Yes, I know I dropped the ball during the session last year, and you all were most kind and understanding of why I did so, and my need to grieve. I thought things would return to “near-normal” this year, and so began coverage of the legislative session with much of my usual, albeit cynical, enthusiasm.

The unrelenting bullying exhibited by our duly-elected legislators changed that.

The Republican legislative leadership had no compunctions about bullying the Democratic governor over his orders to protect the people of this state (including those lawmakers’ constituents) from the worst effects of a viral epidemic. They didn’t hesitate to declare “locals know better than the state” when it came to decisions on whether, when, and how to reopen businesses. Just days later, they turned around and passed a law to prohibit those same local officials from banning firearms in places like schools and parks.

They held public testimony on the budget during the height of the coronavirus pandemic, when there wasn’t even a budget bill filed yet.

They’ve forced the longtime head of the Legislative Fiscal Office, John Carpenter, to retire because they didn’t like the feel of the numbers his staff of accountants were providing, regarding the costs of some of those lawmakers’ schemes.

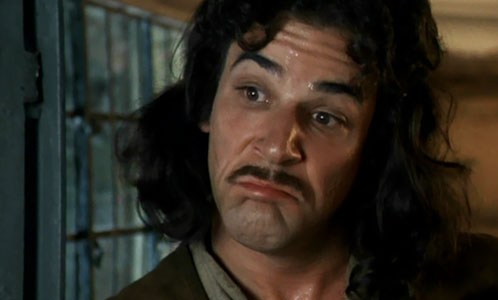

“I do not think that means what you think it means.” – Inigo Montoya in The Princess Bride

Perhaps they simply misunderstand the meaning of the political phrase “the bully pulpit.”

Coined by Teddy Roosevelt, a Republican, and U.S. President from 1901-1909, the change in perception of the meaning has come about because of a change in usage of the word “bully.” At the turn of the 20th Century, “bully” meant “jolly good,” and Roosevelt was saying his office provided a magnificent platform to speak out upon high-minded ideals. In Safire’s Political Dictionary (first published in 1968, last revised in 1993), “bully pulpit” is defined as “the active use of the president’s prestige and high visibility to inspire or moralize.”

But now, “bully” means “a person who habitually seeks to harm or intimidate those whom they perceive as vulnerable,” or as “action of seeking to harm, intimidate or coerce someone perceived as vulnerable.”

Bullies aren’t just schoolyard phenomena. As adults, they manifest as office managers, law enforcement personnel, and state legislators.

Clinical psychologist Dr. Albert J. Bernstein explains why this is so, saying, “Bullies are hooked on excitement. Their drug of choice is anger. Anger is an addiction with bullies. They don’t stop because they’re always getting caught up in the rush of chemicals to their brains. They like power, but they don’t understand it. They aren’t interested in the sedate ways of real power. Bullies are angry people who have discovered, to their delight, that anger – which they would engage in anyway for its thrill value – also gets them power and control, at least in the short run.”

Sound like anyone you know?

Bernstein adds, “Bullies don’t know that anger is something they’re doing; they think it’s being done to them. They say they’re not looking for an altercation; it’s just that they can’t allow people to push them around. Actually, when they’re angry – which is most of the time – they don’t see other people as people at all, but as obstacles.”

We, the people, are obstacles to the growth of power and control being exerted by certain politicians, including those legislators we elected. And in the case of state lawmakers, we’re stuck with this crew of bully-boys for another three and a half years.

When I would see something fundamentally unfair or wrong proposed or enacted by our officials, I would point it out, and try to offer one or more ways to repair the damage being done. Yet as we see our state revenues fall off due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic while business and industry lobbyists froth at the mouth for more tax cuts for them, and as we watch oil and gas prices plummet with lawmakers and industry doing everything possible to salvage our identity as a petro-colonial state, I realize I have no solutions to offer.

I’ve looked at the recommended ways for dealing with bullying: (1) Stay calm, (2) Ask the bully to stop – if it seems safe to do so, (3) Walk away, toward other people, (4) Tell someone so the bully will stop.

That last option is basically appealing to someone with more power who can bully the bully into stopping.

But what do you do when the person at the top is the biggest bully of all, and revels in it?

I can’t stand to watch the legislative committee or floor debates any longer.

I haven’t wanted to watch or listen to the local news.

I’m unplugging from social media.

I’m retiring from the political arena entirely.

I’ve done my part.

I’m choosing to walk away.

Actually, I’ll be rolling away, in this.

I’m renovating it now (the beige and brown hues of the interior are not my “signature colors”), and will begin my adventures in the next couple of months, or as soon as a steady decline in virus infection rates makes it seem safe to do so.

I will be sharing tales of my travels, my reflections from the road, here – as time, your interest, and the Bayou Brief’s illustrious publisher Lamar White, Jr., will permit.

In the meantime, love and light to you all.