Part One: Shreveport and the Patrick Williams Rule

After I declared on social media that I considered the election in Alexandria to be the state’s most fascinating, a friend of mine with ties to Shreveport wrote me privately. “One minor correction,” he said, “Shreveport’s election is the most consequential.” That’s not what I said, I reminded him. I said Alexandria’s was the most fascinating, not the most consequential. There is a difference.

Maybe both of us are correct.

In this commentary, I argue both, using vastly different analytical approaches. In Alexandria, my hometown, the location of the state’s most fascinating election, I rely both on my own personal observations and political science to examine the ways in which whites and blacks have failed the community by both refusing to honestly confront and by cynically exploiting endemic racism as an instrument of political organizing.

But I begin with Shreveport, the consequential election, and I attempt to explain why the absurdly crowded and tightly competitive field could result the third largest city in Louisiana ushering in a new, visionary, young, and progressive era of leadership or a sharp return to a style of power politics and quid pro quo dealmaking that treated elitism as a virtue.

Shreveport’s election is consequential because a relatively unpopular incumbent, Mayor Ollie Tyler, is locked in the toughest battle of her political career, and she does not intend to go down without a fight. When Tyler became the first African American woman elected mayor of a major city in Louisiana, the entire nation took notice, and her victory helped create precedent for two other African American women to win historic victories in the state’s two largest cities, Sharon Weston-Broome in Baton Rouge and LaToya Cantrell in New Orleans.

Tyler’s win may have been an historic breakthrough, but her job performance during the past four years has left many of her own supporters disappointed.

Initially, Tyler drew an astonishing nine opponents. Since then, two of those candidates, Kenneth Krefft, a white Independent, and John-Paul Young, a white Democrat, withdrew.

And then there were seven.

They are: Anna Marie Arpino, a white Independent who allegedly called African Americans “negroes” at an event hosted by an HBCU during her previous run for mayor four years ago and is known for making outlandish statements about her family essentially “building” Shreveport; Tremecius Dixon, an African American Democrat who has largely avoided campaigning; Steven Jackson, an African American Democrat and outgoing Caddo Parish Commissioner who was instrumental in ordering the removal of a white supremacist monument from the front lawn of the parish courthouse (and whose campaign was endorsed by Young, following his withdrawal); Adrian Perkins, an African American Democrat who returned back to Shreveport after a nearly 15 year absence and first announced his intention to run for office in an editorial published in the student paper of his law school in Massachusetts; Jerone Rogers, an African American Democrat and civil engineer; Lee O. Savage, Jr., a white Republican businessman whose campaign biography is heavy with references to his Christian faith and whose platform appears to be a standard recitation of conservative platitudes about crime, gangs, drugs, and unspecified “corruption,” and Jim Taliaferro, a white Republican who appears directly out of central casting for the role of career police officer (which he was and even has the mustache to prove it).

Given the crowded field, the polling is predictably all over the place. Republican-backed polls suggest that one of the two GOP candidates will likely emerge in a runoff election. Other polls suggest the race will come down to two Democrats. But one thing is certain: Mayor Tyler is heavily favored to finish in first place in the primary.

In the absence of public data, some political observers assume that newcomer Adrian Perkins is in the best position to capture the other spot in the runoff election on Dec. 8th, but that analysis is based entirely on Perkins’ strong fundraising numbers. (No one believes Tyler could possibly win outright in the jungle primary.) However, Shreveporters would be wise to remember the Patrick Williams Rule before presuming that a candidate with the most money is necessarily in the best position, especially when voters discover the sources of a candidate’s largesse may not necessarily reflect the values they espouse on the campaign trail.

For those unfamiliar with the Patrick Williams Rule from the 2014 Shreveport mayoral election, the following charts should be illustrative:

The bulk of Perkins’ major contributors, for example, were businesses and individuals tied to the nursing home industry and major engineering firms, which generally prefer conservative candidates.

During the past month, Perkins also played a minor role in the Kavanaugh hearings, signing a letter in support of the judge’s nomination to the Supreme Court and then awkwardly attempting to retract his name from the letter by first blaming The Bayou Brief for reporting it and then his own law school classmates for never getting his permission. (Only seven other students were signatories). Perkins’ response to the controversy was clumsy and strangely conspiratorial, and if your only news source was The Shreveport Times, you may be under the mistaken impression that Perkins’ minor role was a minor story; it actually received hundreds of thousands of readers. Perkins never denied his support for Kavanaugh’s nomination.

Most recently, although it has not yet been disclosed, sources familiar with Perkins’ campaign claim that he has hired a well-known lobbyist and political consultant in Baton Rouge. Three sources told The Bayou Brief that individuals connected with the Perkins campaign have been floating a rumor that Gov. John Bel Edwards plans on endorsing Perkins prior to the election. I reached out to a member of the governor’s senior staff who told me that they had been frustratingly aware of the rumors and then unequivocally denied there was any truth whatsoever to the speculation.

“The governor is not at all issuing an endorsement,” the staffer told me.

At the same time, Steven Jackson’s campaign quietly began making strategic investments in voter contact technology and building up a more durable coalition between African Americans and white progressive voters, many of whom had been initially attracted to Perkins because of his impressive resume but eventually became disillusioned by his aggressive courtship of white social conservatives and big business donors. Some also expressed dismay that Perkins has never before cast a vote in Shreveport.

With only eleven days until the election, the contest in Shreveport may come down to a competition of electoral philosophies: The empowerment model versus the strategic candidate model, which I will explore in greater detail in the discussion about Alexandria.

Although Tyler remains the frontrunner, there has been a long-held assumption that she would likely lose in a runoff election if she faced anyone other than a Republican. That assumption may need to be amended, however, if the Patrick Williams Rule still applies.

For the purposes of full disclosure, I made a personal contribution to Jackson’s campaign after he received threatening and racist hate mail urging him to drop out of the election. I am not involved in his campaign, and I did not consult or interview anyone associated with his campaign about this analysis. I do not regret or apologize for my donation. I regret Louisiana is still a place in which African American candidates are threatened with racist violence merely for having a desire to serve their communities.

Part Two: Alexandria, the Future Great

The managing editor and co-founder of The Alexandria Daily Town Talk, Edgar McCormick, was arguably the greatest cheerleader the city has ever known. McCormick embodied a philosophy that Robert F. Kennedy would articulate nearly a century later. “Some men see things as they are and say why,” Kennedy said. “I dream things that never were and say why not.”

For McCormick, his dreams weren’t just about his fledgling little newspaper; they were about his hometown. In column after column, he extolled Alexandria as “the Future Great.” He imagined it could one day become Louisiana’s answer to Atlanta.

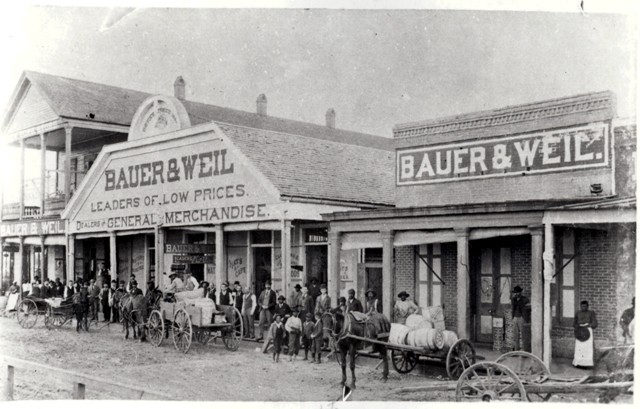

“Undaunted by the ‘postage stamp’ size of his struggling paper, or the fact that rural central Louisiana of the 1880s lacked the means to support a daily, McCormick zealously publicized local affairs, boosted central Louisiana’s farm and timber industries, lobbied for more railroads, promoted town businesses, and championed (with limited results) New South manufacturing enterprises,” the late historian Frederick Spletstoser wrote in his remarkable book The Talk of the Town: The Rise of Alexandria, Louisiana and the “Daily Town Talk.”

McCormick was, in many respects, a man both of his time and ahead of it, but more than anything else, he was someone who considered aspiration to be a virtue.

When I first encountered Spletstoser’s book, I read it in a single day, enthralled not only by the character and the relentless enthusiasm of the man who had founded what would eventually become one of the nation’s most innovative newspapers but also disheartened by the fact that Alexandria never believed in itself as much as Edgar McCormick believed in it. I bought twenty copies of the book from LSU Press. At the time, I’d been working for the newly-elected mayor, Jacques Roy, and the story of McCormick had echoes of the optimistic vision we had crafted during his campaign.

When we had to chose a theme for his first inauguration, we all agreed it should be called, “A renewed spirit.” And during my first few years working for his administration, any time an out-of-towner would arrive to find out exactly what this young new mayor envisioned for a town that the late political writer John Maginnis characterized, perhaps accurately, as a place frozen in time, I would give away one of my own copies of The Talk of the Town. We could be the “Future Great.”

During the past two weeks, I have published two reports on the upcoming mayor’s race in Alexandria, both of which, in various ways, were perceived by some as rabidly critical of one of the three candidates, state Rep. Jeff Hall, an African American Democrat who had run unsuccessfully for the office four years ago.

Although I have grown accustomed to criticism for just about everything I have ever published, I was not prepared for the viciousness I encountered, but in hindsight, I should have been.

I have made it a part of my life’s work to become as knowledgeable as possible on the politics, the history, and the people of my hometown. I’ve written more about Alexandria than any other single subject, and I have always understood, since I was a young boy, that race permeates every aspect of daily life and racism infects the city’s politics like a cancer that at times seems in remission only to reemerge more deadly than ever.

It is difficult to talk about racism in Alexandria, particularly among other white people who do not understand or refuse to acknowledge that racism is structural and institutional and constructed on regimes of power inherited over generations. We lack the vocabulary too often to differentiate between racism and hatred or prejudice, though these concepts can be sometimes interchangeable.

When African Americans from my hometown read a report, written by a white man, that may seem critical of an African American elected official or candidate, some of them may assume the criticism is informed by racial animus. Given our city’s history, this assumption is not without merit, and it is my obligation- indeed, my challenge as a writer- to demonstrate otherwise to a community struggling with the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, and the simple fact that there remain institutional barriers for African Americans to achieve leadership positions in the public and private sectors, despite the fact that Alexandria is a majority-minority city.

But this also requires we all confront some basic truths: There is no excuse for political corruption. We lose our sense of shared humanity when we fail to repudiate a white elected official who builds his political base by accommodating white supremacists just as we do when we fail to reject a black elected official who builds his base by smearing one of his black colleagues merely for speaking with a white constituent, which is what City Councilman Jules Green attempted to do to fellow Councilman Roosevelt Johnson recently.

We also lose our moral and our ethical compasses when we judge people first and foremost by the color of their skin.

Depending on who wins, the next mayor of Alexandria will be the first person in city history to break the so-called “color barrier” or the first person to shatter the glass ceiling. Only one of the three candidates, however, has ever lost and won an election.

For several years, local African American political organizers have argued that the failure of black candidates in mayoral competitions is a consequence of fragmentation and the repeated inability to “clear the field” for a single African-American candidate. This, it turns out, is largely incorrect, at least according to the data. After all, in the 2014 mayoral election, the three African American candidates received a combined total of 45.12%, nearly ten points below the combined total of the two white candidates.

A 2014 study by Dr. Paru Shah, titled “It Takes a Black Candidate,” examines the likelihood of success for African American candidates specifically in local elections in Louisiana, the only state that collects racial demographic data on all candidates, concluding that a black candidate is twice as likely to win in Louisiana if there are multiple black candidates in the race.

Not surprisingly, a black candidate is four times more likely to win if they are already the incumbent. This is not only due to the power of incumbency; it is also due to the fact that approximately 60% of all local elections in Louisiana lack even a single African American candidate. It also speaks to the notion that once a community elects its first person of color in a position of power, that community is far more likely to accept minority leadership in the future.

Dr. Shah’s study also finds that African American candidates, like state Rep. Hall, who have previously run before are five times more likely than others to run again, though prior campaign experience has only a negligible effect on their chances of ultimately winning, particularly in races for mayor or parish president.

After publishing “It Takes a Black Candidate,” Dr. Shah, who earned her PhD in political science from Rice University and is currently a professor at the University of Wisconsin, turned her attention specifically to mayoral elections in Louisiana with minority candidates, collaborating with scholars at Penn State and Ohio State.

Obviously, underlying all of the data are the legacies and realities of discrimination and racism. One of the reasons African American voter registration and turnout in Louisiana lags behind whites is directly due to institutional barriers in education and employment opportunities. We know, for example, that African American candidates are significantly less likely to win office in communities with a high rate of black unemployment. Opportunity begets opportunity.

That said, political science scholarship may also provide a blueprint for an African American candidate to win local and regional elections in Louisiana, and this could explain why state Rep. Hall now appears to be losing ground.

Even in majority-minority communities like Alexandria, black candidates seeking citywide offices are never successful when their campaigns exclusively concentrate on bolstering and cultivating support among other African Americans (i.e. the empowerment model). This is not merely because of registration and turnout numbers, though; it is also because voters of both races prefer candidates whose campaigns engage in coalition building (i.e. the strategic candidate model).

There may still be enough time for state Rep. Jeff Hall to bounce back into a more competitive position in the race to become the next mayor of Alexandria, Louisiana. Yesterday, U.S. Rep. Cedric Richmond, the lone Democrat in the state’s federal delegation, endorsed Hall at a small event the Hall campaign called, somewhat ironically, a “Unity Rally;” none of Hall’s competitors had been invited.

The event was sparsely attended; between three and four dozen people showed up, according to one participant and based on video footage and photographic documentation of the event. Richmond delivered an almost identical speech he had given a couple of months prior in New Orleans in support of Texas congressional candidate Colin Allred, an African American Democrat in Dallas who is locked into a close race with long-time Republican incumbent Pete Sessions. (Full disclosure: I personally contributed to Allred, who lives within earshot of my former home in Dallas).

In their study of successful black mayoral candidates, the four political science scholars arrive at a simple but profound conclusion: To win, an African American candidate must first demonstrate their viability in the primary election, and viability means more than merely shoring up the entire available universe of black voters. There is no meaningful increase in voter turnout in a primary election featuring a black candidate (the attendance at Rep. Richmond’s rally is illustrative); the increase only occurs during a runoff election.

However, win or lose, there are already lessons to be learned from Hall’s campaign strategy, particularly for those in Alexandria who have long hoped the majority-minority city could one day elect a person of color to lead City Hall.

As I reported previously, a local nonprofit is currently circulating a sample ballot that falsely asserts former President Barack Obama endorsed a slate of local candidates based on their race.

Here is what the former president actually said on the subject:

“We need to reject any politics that targets people because of race or religion. This isn’t a matter of political correctness. It’s a matter of understanding what makes us strong. The world respects us not just for our arsenal; it respects us for our diversity and our openness and the way we respect every faith.”

****

Yet Robert F. Kennedy may have articulated this idea better than anyone, and, in so doing, provided a model for a “future great” to which all of us should aspire. Quoting in full:

“We must admit the vanity of our false distinctions among men and learn to find our own advancement in the search for the advancement of others. We must admit in ourselves that our own children’s future cannot be built on the misfortunes of others. We must recognize that this short life can neither be ennobled or enriched by hatred or revenge.

“Our lives on this planet are too short and the work to be done too great to let this spirit flourish any longer in our land. Of course we cannot vanquish it with a program, nor with a resolution.

“But we can perhaps remember, if only for a time, that those who live with us are our brothers, that they share with us the same short moment of life; that they seek, as do we, nothing but the chance to live out their lives in purpose and in happiness, winning what satisfaction and fulfillment they can.”