When I die, I want to be buried in St. Martin Parish so I can remain politically active.”

With the arguable exception of Illinois, there is perhaps no other place in the country with a reputation for political corruption as legendary or as colorful as the “Gret Stet” of Louisiana. The stories are legion, but considering the recent ill-fated attempts by President Donald Trump and a contingent of his Republican loyalists in Congress to shamelessly overturn the results of the 2020 election by concocting a series of fantastical and ultimately baseless allegations of “voter fraud,” there are at least a couple of classics from Louisiana’s past that jump out.

In 1957, four years after voting machines were mandated statewide, Gov. Earl K. Long, the wily younger brother of the martyred Kingfish, fresh off of a commanding victory over his arch-nemesis, New Orleans Mayor deLesseps Story “Chep” Morrison, and still basking in the afterglow of his triumphant return to power, convinced his allies in the legislature to establish a new position.

It was part of a four-pronged package of so-called “reforms,” each intended to gut the Office of Secretary of State, then held by another one of Long’s political enemies, Wade O. Martin, by stripping away all of his most important powers and responsibilities. This included, most critically, control over the new instrument of American democracy, the voting machine.

For nearly 40 years, Louisiana’s Custodian of Voting Machines, once described by Governing Magazine as “the most ridiculous elective office in American state government,” was also “the personal possession of a single family.”

Originally, the custodian was appointed by members of a newly-established Board for Voting Machines, who each served at the pleasure of the governor.

“Gimme five (voting) commissioners,” Earl K. Long famously boasted, “and I’ll make them voting machines sing ‘Home Sweet Home.'”

But by the time term limits forced Long to step down from office in 1960 (which would also be the last year of Long’s life), the Custodian of Voting Machines had become an elected position.

Douglas Fowler, a Long crony from the small town of Coushatta, the seat of Red River Parish in northwest Louisiana, became the first person actually elected to the job (subsequently rebranded as “Commissioner of Elections” in the mid-70s), holding onto power until his retirement in 1979, at which point his son Jerry, a former professional football player for the Houston Oilers, took the reins. Jerry would win five consecutive terms before an illegal kickback scheme landed him in the federal penitentiary in 1999.

Two years later, at the dawn of the new millennia, the Louisiana legislature decided to eliminate the office entirely, assigning the responsibilities back with the Secretary of State. Leery of the potential for partisan abuse, the new law also included a provision that prohibited the Secretary of State from “raising political funds, assisting any candidate, or participating in party activities of any kind.” In other words, Louisiana’s Secretary of State isn’t allowed to participate in any campaign other than their own.

Good luck trying to enforce the prohibition, however. Last year, shortly after we pointed out that the office’s current occupant, Republican Kyle Ardoin, had violated the law by participating in a campaign rally held by Donald Trump, Ardoin was invited back on stage at another Trump campaign rally by the state’s chief legal officer, Attorney General Jeff Landry.

Louisiana has done very little to discredit the notion that political corruption is more rampant within its borders than it is practically anywhere else in America. Occasionally, it can seem as if the state actually relishes in the notoriety. At the very least, it can be said that Louisiana takes pride in its peculiar and sometimes arcane political traditions. In 1932, U.S. Sen. Tom Connally of neighboring Texas advised anyone who believed they knew everything there was to know about politics to “go down to Louisiana and take a postgraduate course.”

I’ll leave it to others to determine whether Louisiana’s reputation was ever legitimately earned, but I would caution against reaching any conclusion, particularly as it relates to the subject of “voter fraud,” until considering first the larger context.

Earl K. Long, for example, may have been corrupt for a whole host of reasons, but one thing is for certain: He didn’t know a damn thing about hacking into a voting machine and altering the results of an election. If he had, then it’s unlikely he would have suffered a pair of humiliating losses in 1959 when he ran for Lieutenant Governor and for what should have been a shoo-in spot as Winn Parish’s representative on Louisiana’s Democratic State Central Committee. His quip about commanding the state’s voting machines to play “Home Sweet Home” can only be understood as a playful taunt against his political adversaries, the vast majority of whom were rattled and threatened by Long’s enormously successful efforts to expand the state’s voter rolls by eliminating barriers that had deliberately disenfranchised hundreds of thousands of Black Louisianians.

Indeed, when you scratch beneath the surface of almost every story about “voter fraud” from Louisiana’s past, you will likely be confronted with the distinct possibility that the controversy was cooked up, fabricated by an almost exclusively white and predominately conservative political establishment staunchly opposed to any effort that expanded access to the polls or better protected the rights of a predominately Black and historically marginalized electoral minority.

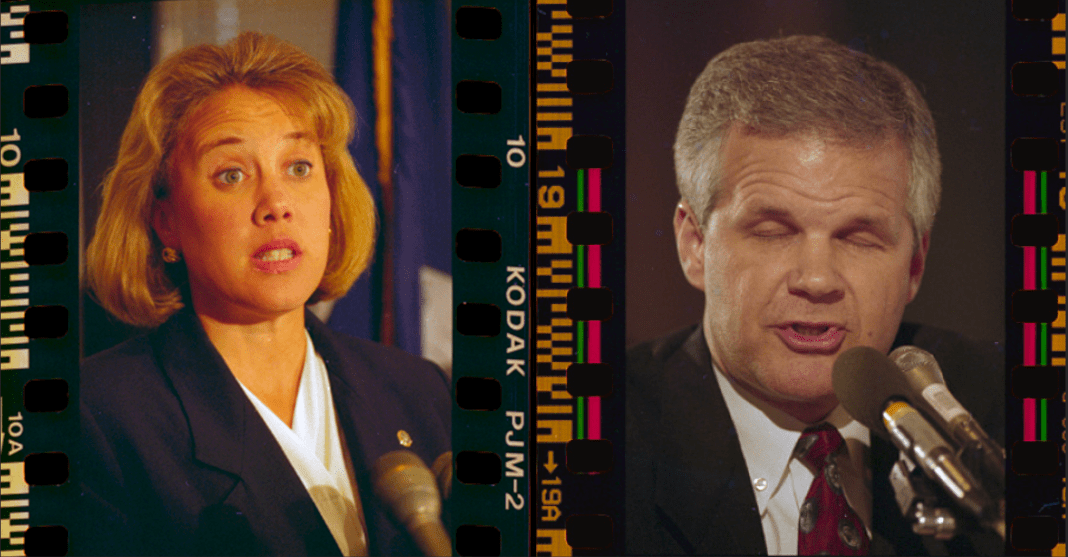

There is perhaps no better example of this dynamic and its enduring mythos than one of the closest elections in state history: the contentious race in 1996 for J. Bennett Johnston’s seat in the United States Senate. It’s a saga worth revisiting, not simply because we now have the benefit of hindsight, however helpful it may be, but also because of the staggering similarities between the wild and mendacious allegations of “voter fraud” currently being leveled by President Donald Trump and the claims that were made nearly a quarter of a century ago by a lesser-known Republican loser named Woody.

“Mr. Michael Douglas,” the Military Social Aide announced in a booming baritone, signaling the famous actor to shuffle up the receiving line at the White House, where President Bill Clinton, beaming, stood beside his guest of honor that night, French President Jacques Chirac. Seconds before, the actress Candace Bergen had breezed by.

That night, the place was ablaze with some serious star power. This was, after all, a State Dinner at the Clinton White House. Gregory Peck was there, as were the novelist John Grisham, the fashion designer Oscar de la Renta, the architect I.M. Pei, and Stephen Sondheim, the renowned composer.

“Hold on,” Clinton told Douglas, “I think I’m standing in your spot.” Clinton slid to the side, and Douglas laughed along with the joke. His most recent leading role was in the hit film “The American President.”

It was Feb. 1, 1996.

The menu that evening began with lemon lobster thyme with roasted eggplant soup followed by a rack of lamb with winter fruit and pecans, a layered artichoke salad with an endive balsamic dressing, and, for dessert, an apple and cherry sherbet pyramid with peanut butter truffles and white almond bark chocolate fudge. Of course, since this was in honor of France, there was also an ample supply of wine, primarily from California and Oregon. The chef would later claim that the meal was inspired by the First Family’s new health kick.

Also that night, U.S. Sen. John Breaux, a two-term Democrat from Crowley, Louisiana, brought along a special guest of his own.

During the previous three and a half months, Mary Landrieu had barely left her house. The then-outgoing state treasurer, who had only recently turned 40, was exhausted, physically and emotionally drained.

Her 1995 campaign for Louisiana governor, which once appeared to be on the brink of making history, had fallen short in a crowded jungle primary. The loss, she knew deep down, had less to do with any missteps she had made and much more to do with the machinations and the “unholy alliances” of the good ol’ boy’s club in Baton Rouge. But that’s another story.

Suffice it to say, it’s hard to blame Landrieu for being dispirited by what she had just experienced. Later, she would look back on the days and weeks after the ’95 campaign as the lowest point in her entire career.

John Breaux, however, thought there was an obvious silver lining to Landrieu’s loss, and while he and his wife Lois had invited Mary and her husband Frank up to D.C. under the pretense of a State Dinner, his real purpose was to talk with her about a job opportunity. J. Bennett Johnston, who’d arrived in the Senate in 1972, was ready to retire, and Breaux believed there was only one candidate in Louisiana who could keep that seat for the Democrats.

At the time, running another statewide campaign for office had been the furthest thing from her mind. She’d spent the better part of the past two years thinking of all of the things she would do if she became governor. There were mountains of policy white papers and stacks of draft legislation, not to mention all of the things she’d picked up on the campaign trail. She had hoped to put education front and center in her administration, not something you can really do as a member of the U.S. Senate. She and Frank had two small children, and they’d wrapped their heads around how to make things work, logistically, if they were to move into the Governor’s Mansion in Baton Rouge. But splitting her time in between D.C. and Louisiana? That would be tough.

Never mind all that, Breaux told her.

The night before the State Dinner, John and Lois welcomed their guests from back home with a pot of homemade gumbo. Damn good gumbo, Landrieu still recalls all of these years later.

Now wasn’t a bad time for her to run, Breaux told her. It was the perfect time. Name recognition was never an issue for the daughter of former New Orleans mayor and HUD Secretary Moon Landrieu and someone who’d entered public service in her own right at the age of 23 and already had won two statewide elections for treasurer.

Yes, she’d fallen short of winning the governor’s race, but she still had a real statewide infrastructure and a constellation of supporters, especially women, who would be willing, ready, and able to hit the ground running.

They were still with her, and so was John Breaux, who, with Johnston’s impending retirement, would become Louisiana’s senior United States Senator and the state’s highest-ranking Democrat.

Mary Landrieu officially launched her campaign for the Senate on May 15, 1996 by kicking off a three-day statewide tour in her hometown of New Orleans. But she first made the decision to run in February, after a discussion over the kitchen counter and a bowl of gumbo at John Breaux’s Washington townhouse.

No one recruited Louis Elwood Jenkins, Jr. to run for the United States Senate. Not that it would have mattered. The longtime Baton Rouge state representative, better known by his nickname “Woody,” had already tried and failed twice before, first in 1978 and then again two years later in 1980.

Despite his previous losses, by 1996, Jenkins, the owner of a couple of fledgling, “low-power, Class A” television stations in Baton Rouge, believed that the timing was finally ripe for his stridently conservative brand of politics. Like countless others, Jenkins had only recently switched to the Republican Party, which, even in the mid-90s, was still in its nascency in Louisiana. If he succeeded, he would become the first Republican from Louisiana elected to the Senate since Reconstruction.

But for someone who had spent 24 years serving in the state legislature, joining when he was still in his final year at LSU Law, Jenkins’ record was remarkably flimsy—heavy on grandstanding but light on accomplishments. He was more of an ideologue, known primarily as an anti-abortion zealot, than a deal-maker, but it’s easy to understand why someone like Woody Jenkins could convince himself that the ascendancy of the religious right and the so-called “moral majority” had cleared a path that would lead him into the world’s greatest deliberative body.

All told, 14 others, including Landrieu, qualified to run for Johnston’s soon-to-be-vacant seat that year. Jenkins wouldn’t make the same mistakes he had in the past. This time, buoyed by the support of his allies in the religious right, including, most notably, his campaign manager, a newly-elected state representative named Tony Perkins, Woody Jenkins could afford to run things more professionally.

Five other Republicans signed up for the race, including sitting U.S. Rep. Jimmy Hayes, who, like Jenkins, had also recently defected from the Democratic Party, and the state’s most virulent racist since Leander Perez, former klansman David Duke, whose political stock had plummeted considerably since his landslide loss to Edwin Edwards in 1991 but who nevertheless still commanded a significant constituency on the far-right. Importantly, though, there wouldn’t be a party primary; instead, the first round would be a Louisiana specialty—the notoriously unwieldy and often unpredictable jungle primary.

If Jenkins had any doubt whether he had misjudged the moment, it likely disappeared on the night of Sept. 30, 1996, when it became clear that not only had he survived the jungle primary, he would be heading into the runoff against Mary Landrieu as the clear frontrunner.

Jenkins had good reason to feel confident of his chances. Landrieu had squeaked into second place by a margin of only 14,000 votes over state Attorney General Richard Ieyoub, a fellow Democrat. But even more importantly, the Republican candidates had garnered a combined total of 54% of votes.

Woody Jenkins didn’t wait to get to work. He hired Roy Fletcher, a hard-nosed political consultant with good instincts and the kind of institutional knowledge that money can’t buy. Fletcher came with another important asset: He also ran Republican Gov. Mike Foster’s campaign shop. Almost immediately, he began cutting ads for Jenkins that put the endorsement of the popular incumbent governor front and center.

Privately, Tony Perkins, on behalf of the Jenkins’ campaign, opened up a back-channel with David Duke, negotiating a deal to purchase the former klansman’s voter database and “computerized calling service” for the tidy sum of $82,500, something that would only become known later (along with the disclosure that Foster had spent nearly twice as much with Duke). In 2002, the Federal Elections Commission handed Jenkins a $3,000 fine for illegally concealing the purchase. Had it been known at the time, it’s likely that voters wouldn’t have been as forgiving as the FEC, something that Jenkins and Perkins must’ve recognized at the time. Whatever marginal benefits they may have gained by purchasing access to Duke’s political operation would have never been enough to overcome the public backlash. Woody Jenkins didn’t want his supporters to know that his campaign was literally enriching the country’s most notorious white nationalist. (Incidentally, by the time the FEC finally took action against Jenkins in 2002, Tony Perkins was challenging Landrieu’s reelection. Perkins finished in a distant fourth place, capturing less than 10% of the vote in the jungle primary, and Landrieu ultimately prevailed in the runoff against Republican Suzie Haik Terrell).

The campaign’s “deal with the devil,” as it were, may have been kept secret from the public, but there was at least one problem that Jenkins couldn’t conceal: The more voters got to know Woody Jenkins, the less they liked him.

During a televised debate with Landrieu, when asked whether he would support increased federal funding for AIDS research, Jenkins didn’t mince words.

“I probably would support less (funding),” he said, “because I think the answer to the AIDS problem, in terms of the contagious nature of it, is in 90% of the cases very simple. We need to make sure that gay people stop engaging in the acts that they are engaging in. If they would do that, that’s gonna stop 90% of the AIDS problem. You don’t need a lot of education for that, because they know exactly what they’re doing and what’s causing it.”

Woody Jenkins’ cavalier cruelty—his outlandish bigotry—wasn’t limited to gay people; it also wasn’t especially noteworthy in a race that had also included David Duke. His comments about AIDS funding, for example, barely registered in the press coverage, but nonetheless, the remarks are a good illustration of why Jenkins struggled with a fundamental issue, his own likability. Instead of presenting himself as a humble but earnest Christian conservative, Jenkins often came across as an arrogant, patronizing, holier-than-thou charlatan.

“If you’ve got someone whose running for office who thinks they’re anointed from God to have a certain position, and when the voters decide they’re not so anointed,” Orleans Parish Clerk of Criminal Court Edwin Lombard would later remark about Jenkins, “you’re going to have problems.”

There’s at least one other issue that made Jenkins distinguishable from mainstream Republicans: His bizarre and half-baked proposal to eliminate income taxes, shut down the IRS, and enact a nationwide sales tax, which he insisted would be no higher than 15% but economists said would have to be closer to 35% to 40% to work.

Jenkins made the quixotic plan the centerpiece of his campaign, seemingly indifferent to the fact that, even if he were to win, his harebrained proposal had no chance of even making it to the Senate floor, much less being enacted into law.

By the eve of the election, Landrieu’s campaign had a good reason to feel at least cautiously optimistic. The latest statewide poll had their candidate up by six points, outside of the margin of error, and they had executed a nearly flawless effort against Jenkins during the runoff. Democratic voters appeared to be solidly united behind them, and they had largely succeeded in defining their Republican opponent as a radical right-wing extremist whose views were well outside of the mainstream and who seemed far more interested in embarking on an ideological crusade than in the actual job of a United States Senator.

On the other hand, Jenkins, we can surmise, must’ve been supremely confident that he would go to sleep the next day as Louisiana’s newest Senator-elect.

No one could have predicted an Election Day that began on Nov. 5, 1996 but wouldn’t end until Oct. 1, 1997.

If there is one fundamental maxim about close elections in Louisiana, it is this: Wait for Orleans Parish.

Orleans is a deep blue bastion in a blistering red desert. In recent years, it frequently appears like a mirage, giving false hope to the supporters of far too many Democratic candidates than can be named. But every now and then, when it looks as if an election has been signed, sealed, and delivered to a Republican, Orleans pours in a deluge of votes and suddenly, miraculously, the election swings irretrievably, and the Democrat prevails.

Orleans Parish is notoriously—some may argue deliberately; others may say smartly—the last to post its election returns.

On the night of Nov. 5, 1996, for more than two glorious hours, Woody Jenkins watched as he built a commanding 95,000 vote lead over Mary Landrieu and then, for more than two agonizing hours, he watched as his lead evaporated.

By the time all 1,700,102 votes had been counted, Mary Loretta Landrieu defeated Louis Elwood Jenkins, Jr. by a razor-thin margin of only 5,788 votes. Voters in Landrieu’s native Orleans Parish were single-handedly responsible for snatching away from Jenkins what would have otherwise been a 53% victory.

Landrieu became the first woman from Louisiana elected to serve in the United States Senate, and that same night, Bill Clinton became the first Democratic president since Franklin Delano Roosevelt to win a second term in office. And just as he had four years before, he painted Louisiana blue.

Landrieu took the stage in front of her supporters at the Fairmont Hotel (now known by its former name, the Roosevelt) in New Orleans ten minutes after midnight. 15 minutes later, when Jenkins addressed his supporters in Baton Rouge, he offered no concession.

The next morning, he announced his intention to file an official challenge, citing a hodgepodge assortment of vague allegations about potential “voter fraud” and illegal vote buying.

“One of the issues out of many that we will look at is whether or not there was a tainting of this election by gambling money that was brought into this state and spent illegally. Corporate contributions are illegal in senatorial races, and we need to find out the facts,” said Jenkins, who was actively and illegally concealing his campaign’s financial ties with David Duke, a Nazi sympathizer and former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

“Who paid people out on the streets?” Jenkins asked rhetorically. “Who paid for transportation?”

Two weeks later, Jenkins abandoned a formal challenge, claiming he didn’t have a sufficient amount of time to build his case, and instead took his complaints to the Republican-controlled Senate, where he correctly believed he’d find a more receptive audience willing to entertain his inchoate and almost entirely speculative allegations.

It should be noted upfront that mistakes are a part of every major election because elections are run by human beings and human beings make mistakes. But after the Senate concluded its ten-month-long, bipartisan investigation into Woody Jenkins’ claims of a stolen election, it found absolutely no evidence of the kind of pervasive and systemic fraud or corruption that could have conceivably altered the results in his favor.

Among other things, Jenkins claimed the election was tainted by more than 7,000 “phantom voters,” an amorphous and poorly-defined term that he applied to characterize discrepancies typically attributable to a malfunctioning machine or human error. In any event, the General Accounting Office concluded that 98% of Jenkins’ “phantom voters” were not, in fact, “phantom voters,” and Jenkins, by his own admission, could only identify, at most, 200 votes that he alleged to be duplicative, not even remotely close to the nearly 5,800 votes he would need to alter the results of the election.

His campaign also claimed that thousands of voter signatures didn’t match, though when they were finally forced to cough up evidence, they could only provide the names of 65 people, all of whom happened to be Black residents of New Orleans and many of whom were later located and confirmed to be legitimate. At least initially, Jenkins had floated an allegation that more than 1,300 voters had listed their address as a recently demolished public housing project, but again, when they were pressed to provide evidence of this claim, they walked back the assertion, suggesting that a computer glitch may have resulted in an inaccurate tabulation.

At one point, Jenkins even claimed that his campaign had interviewed people who alleged that they were paid to cart voters around from one polling place to another so that they could vote multiple times, but he refused to provide the names of any of those individuals, asserting that they feared they could be “murdered” if their names were ever revealed publicly.

The Landrieu campaign conducted their own investigation and discovered Jenkins had hired a convicted felon with a long record of crimes of dishonesty to locate people willing to testify that they had been paid to vote for Landrieu. According to Landrieu’s campaign, the man hired by Jenkins had been offering to pay people for their testimony, allegations that Jenkins would deny, though ultimately, it was rendered moot when the effort failed to produce anything even remotely credible.

The investigation dragged on for 10 grueling months. But in the end, on Oct. 1, 1997, the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration voted 16 to 0 to dismiss Jenkins’ complaint. Committee Chairman John Warner, a Republican from Virginia, “reported that the committee had found ‘a failure of safeguards and discrepancies in records. It has revealed possible campaign finance violations, although no indication of such violations on the part of Senator Landrieu. It also has revealed isolated instances of fraudulent or multiple voting and improper or duplicate registrations. But it has not revealed an organized, widespread effort to illegally affect the outcome of this election. It has not revealed an organized, widespread effort to buy votes, or to procure multiple votes, or secure fraudulent registrations.’ Nor was there evidence ‘to prove that fraud or irregularities affected the outcome of the election. Finally, it has never been alleged, and no evidence has been uncovered, that Senator Landrieu was involved in any fraudulent election activities.'”

The close election earned the new United States Senator from Louisiana a nickname that would follow her throughout her political career, Landslide Landrieu. But to her credit, Landrieu used the experience as a way of motivating voters during her subsequent campaigns, reminding supporters that in her first race for the Senate, her margin of victory was roughly the same as one vote for every precinct in Louisiana. After beating Terrell in a runoff in 2002 and the state’s current junior U.S. Senator, John Neely Kennedy, in the primary in 2008, Landrieu’s luck ran out in 2014, when Bill Cassidy, a Republican physician from Baton Rouge, bested her in a race that was largely defined as a repudiation of President Obama instead of a referendum against her or her record.

Coda

Some may argue that Woody Jenkins was well within his rights and perfectly justified in pursuing his complaint, but that, I think, is only partially true. His rights were well-established but his justification had always been absurd.

It’s impossible to know whether he would have taken the same course of actions if his opponent hadn’t been a woman, but it’s also hard to imagine the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration treating a male colleague the way they treated Landrieu. In the end, even though she was completely vindicated and proven to have been a duly-elected member of their august body, the committee rejected a proposal to reimburse Landrieu’s legal expenses, all of which had been incurred as a direct result of their dilatory treatment and nakedly partisan posturing.

On the night of Landrieu’s victory, seven other women were also on the ballot as candidates for the U.S. Senate; only one of them, Susan Collins of Maine, was successful.

Sexism was a part of this story, but there’s another aspect of this that also floated directly below the surface and was also never properly acknowledged or addressed.

As the Senate’s investigation in 1997 progressed, many, including some of Jenkins’ Republican allies, became increasingly disconcerted by his campaign’s nearly exclusive focus on a very specific subset of the electorate, predominately Black voters in and around the city of New Orleans.

Jenkins’ early and wildly inaccurate claims about “phantom voters,” for example, were almost entirely alleged to have originated in Orleans Parish, which fit in neatly with racist tropes about Black criminality and the notion that political corruption was primarily an urban phenomenon. Yet if Jenkins had applied the same methodology his campaign used to calculate the number of “phantom voters” in Orleans Parish in Louisiana’s other 63 parishes as well, he would have discovered the same innocuous and statistically insignificant discrepancies occurred at essentially the same rate across the entire state.

Perhaps more troubling were Jenkins’ relentless attacks against individuals and organizations who provided voters with free transportation to the polls. It was a not-so-subtle implication that there was something inherently corrupt with any effort that expanded access for those who simply wanted to exercise their fundamental right to vote. To be sure, the investigation did fault former New Orleans Mayor Marc Morial’s political organization for not filing all of its necessary paperwork with the FEC, but his negligence pales in comparison to Jenkins’ decision to deliberately and illegally conceal from voters his campaign’s $82,500 expenditure with David Duke.

While Jenkins himself may never recognize it, at the core of practically all of his allegations, there seems to be an underlying assumption that the votes of Black people should be subjected to a heightened standard of scrutiny.

Since the facts make it clear that it’d be disingenuous to characterize this protracted dispute as something noble or principled, you may be wondering, after all of this, if it’s really fair to suggest that this was actually some sort of elaborate plot by the GOP to steal a Senate seat. Isn’t it really a rather pathetic crusade by a grandstanding alpha-male who simply refused to believe that he lost to a woman? Certainly that’s how many characterized it at the time. Still, it’s important to note that Jenkins’ campaign had received the endorsements and the support of the entire Republican establishment, including former President George H.W. Bush, Republican presidential nominee Sen. Bob Dole, Sen. John McCain, Majority Leader Trent Lott, and many others. Republicans almost certainly recognized that Jenkins’ allegations dead-ended months before they finally decided to pull the plug on their investigation and stop the charade.

In 1999, two years after the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration dashed his dreams of joining their ranks, Woody Jenkins launched another statewide campaign for a different office, Commissioner of Elections, the job Uncle Earl called “Custodian of Voting Machines.” But alas, the numbers once again didn’t add up in his favor. Jenkins lost in a runoff to fellow Republican Suzy Haik Terrell, the same Suzy Haik Terrell who would lose in a runoff against Mary Landrieu three years later.

Woody Jenkins still believes that he won in 1996 and that his victory was stolen from him, and among many Louisiana Republicans, the fantastical allegations he concocted about voter fraud and vote-buying in New Orleans are considered to be gospel truth, repeated with conviction and usually embellished with even wilder details any time a close election requires people to wait for Orleans Parish.

Earlier, I suggested that on the day before the 1996 runoff election, no one could have predicted the events that would ultimately transpire, but that’s not entirely true. No doubt, some in Louisiana remembered what had occurred 16 years prior, in 1980, when Huey’s son and Earl’s nephew, Russell Long, beat Jenkins by double digits and secured his seventh consecutive term in the United States Senate.

“In a news conference at the state Capitol, (Woody) Jenkins questioned the ‘propriety’ of Long hiring a large number of Black ‘field coordinators’ and thousands of other individuals to help get out the vote,” Ronnie Patriquin of The Shreveport Journal reported on Oct. 17, 1980. “‘How many people can you employ in a campaign before it becomes akin to vote buying?’ Jenkins asked, noting ‘the interesting thing is if you pay someone $5 or $10, that’s vote buying, but if you pay someone $40 or $50, that’s not.'”

Among other things, Jenkins alleged, again without any evidence, that Long hired and paid 6,000 Black workers on Election Day, a claim that Long’s campaign team called “ridiculous.”

“It is unfortunate that Mr. Jenkins cannot accept the fact that the voters of Louisiana overwhelmingly rejected him,” Long said, “not only on Sept. 13 (1980), but two years earlier when he suffered another defeat in his race against J. Bennett Johnston.”

Russell Long was just warming up. “Mr. Jenkins will try to find every conceivable excuse for explaining his repeated failures at the polls,” he said. “It is consistent with his brand of campaigning to continue with his distortions and lies even after an election is over. I hope that Mr. Jenkins is enjoying his sour grapes and that he is pleased to feast on them for the next six years.”

On Monday, Woody Jenkins spent about an hour inside of the Senate chambers in the Louisiana state Capitol. Even though he retired from the state legislature 20 years ago, Jenkins had to take care of some official business. As one of the state’s two at-large Republican electors, Woody Jenkins was there to cast his vote in the Electoral College for President Donald J. Trump, who carried Louisiana and its eight electoral votes by capturing more than 58% of the vote.

To the best of my knowledge, despite the state being required by court order to expand mail-in voting and despite its use of Dominion Voting Systems’ machines and software, neither Trump or Jenkins or anyone else for that matter have alleged that Louisiana’s elections this November were somehow riddled with rampant voter fraud or were otherwise rigged or tainted in any way.

The machines were so finely tuned, in fact, that if you listened closely enough, you could hear them playing “Home Sweet Home.”